Reed McConnell at Cabinet Magazine:

When the angels appeared to John Ballou Newbrough early one morning in 1881, he was nothing if not well prepared. A dentist and Spiritualist, he had spent the last ten years purifying himself for supernatural contact by abstaining from meat, bathing twice a day, and rising before dawn. The visit was expected.

The angels wanted him to buy a typewriter, a newfangled device—Newbrough described typing as writing “by keys, like a piano” in a letter to the Boston Spiritualist journal The Banner of Light—that would allow him to transcribe their account of the world’s true spiritual history. He obeyed, and for the next fifty weeks the angels visited him in his New York City apartment every morning before sunrise, taking control of his hands in sessions that lasted exactly fifteen minutes. By the end, Newbrough had produced a nine-hundred page manuscript called Oahspe: a history of world religions that exposed their lies and elucidated their fundamental interconnections.

The dictating angels were nothing if not thorough. To supplement the text, they provided Newbrough with images of religious leaders, which he painted in the dark. Among those reproduced in the 1891 edition of Oahspeare the austere, mustachioed Zarathustra, with a cherub grinning behind his left shoulder, and a serenely smiling Confucius, hair stroked by a ghostly figure while an enormous eye floats in the clouds above him.

more here.

Every era gets its own Thomas Cole, the British-born, nineteenth-century artist who ushered in a new age of American landscape painting. In the 1930s and 1940s, he was a precursor to artists like Grant Wood. Come the 1960s and 1970s, MoMA linked his brushwork to abstract expressionism. In the late 1980s, he was part of a Reaganesque “Morning in America” campaign, a Chrysler-sponsored survey of American landscape paintings at the Met. Now, also at the Met, “Thomas Cole’s Journey: Atlantic Crossings” positions Cole as a challenge to Trumpian greed, as well as to the American landscape as imagined by Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke and EPA chief Scott Pruitt. But while Cole was undoubtedly concerned with the land he painted, he was not exactly the convenient social critic the Met portrays.

Every era gets its own Thomas Cole, the British-born, nineteenth-century artist who ushered in a new age of American landscape painting. In the 1930s and 1940s, he was a precursor to artists like Grant Wood. Come the 1960s and 1970s, MoMA linked his brushwork to abstract expressionism. In the late 1980s, he was part of a Reaganesque “Morning in America” campaign, a Chrysler-sponsored survey of American landscape paintings at the Met. Now, also at the Met, “Thomas Cole’s Journey: Atlantic Crossings” positions Cole as a challenge to Trumpian greed, as well as to the American landscape as imagined by Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke and EPA chief Scott Pruitt. But while Cole was undoubtedly concerned with the land he painted, he was not exactly the convenient social critic the Met portrays. New words enter English in a variety of ways. They may be imported (

New words enter English in a variety of ways. They may be imported ( To investigate chimp communication, my colleagues and I follow chimpanzees through the forest as they go about their lives. We carry a hand-held “shotgun” microphone and a digital recorder, waiting for them to call.

To investigate chimp communication, my colleagues and I follow chimpanzees through the forest as they go about their lives. We carry a hand-held “shotgun” microphone and a digital recorder, waiting for them to call. The encouragement that the fifty-five-year-old psychology professor offers to his audiences takes the form of a challenge. To “take on the heaviest burden that you can bear.” To pursue a “voluntary confrontation with the tragedy and malevolence of being.” To seek a strenuous life spent “at the boundary between chaos and order.” Who dares speak of such things without nervous, self-protective irony? Without snickering self-effacement?

The encouragement that the fifty-five-year-old psychology professor offers to his audiences takes the form of a challenge. To “take on the heaviest burden that you can bear.” To pursue a “voluntary confrontation with the tragedy and malevolence of being.” To seek a strenuous life spent “at the boundary between chaos and order.” Who dares speak of such things without nervous, self-protective irony? Without snickering self-effacement? 1. Your perspective on yourself is distorted.

1. Your perspective on yourself is distorted. Since 2013,

Since 2013,  In 1954, on holiday in Mexico, Norman Mailer discovered weed. He had smoked it before, but this time was different. He experienced “some of the most incredible vomiting I ever had … like an apocalyptic purge”. But soon “I was on pot for the first time in my life, really on.” His second wife, the painter Adele Morales, was sleeping on a couch nearby. “I could seem to make her face whoever I wanted [it] to be,” Mailer wrote later, in the journal he kept during his marijuana years. “Probably could change her into an animal if I wished.” After that he got high on a regular basis. On “tea” (he called his weed diary “Lipton’s Journal”), he felt that “For the first time in my life, I could really understand jazz.” He also got to know the mind of the Almighty, which bore, he discovered, a marked resemblance to his own. Hotboxing in his car every night for a week, Mailer groped his way to the ideas that would shape his work during the 1960s and beyond. They were not, on the whole, very good ideas. But by 1954 Mailer was a desperate man. He was thirty-one and had published two novels: The Naked and the Dead (1948), which had been a smash, and Barbary Shore (1952), which had tanked. He felt like a failure. He needed “the energy of new success”. Eventually, of course, new success would come. But things had to get a lot worse before they could get better.

In 1954, on holiday in Mexico, Norman Mailer discovered weed. He had smoked it before, but this time was different. He experienced “some of the most incredible vomiting I ever had … like an apocalyptic purge”. But soon “I was on pot for the first time in my life, really on.” His second wife, the painter Adele Morales, was sleeping on a couch nearby. “I could seem to make her face whoever I wanted [it] to be,” Mailer wrote later, in the journal he kept during his marijuana years. “Probably could change her into an animal if I wished.” After that he got high on a regular basis. On “tea” (he called his weed diary “Lipton’s Journal”), he felt that “For the first time in my life, I could really understand jazz.” He also got to know the mind of the Almighty, which bore, he discovered, a marked resemblance to his own. Hotboxing in his car every night for a week, Mailer groped his way to the ideas that would shape his work during the 1960s and beyond. They were not, on the whole, very good ideas. But by 1954 Mailer was a desperate man. He was thirty-one and had published two novels: The Naked and the Dead (1948), which had been a smash, and Barbary Shore (1952), which had tanked. He felt like a failure. He needed “the energy of new success”. Eventually, of course, new success would come. But things had to get a lot worse before they could get better. Tom Wolfe died yesterday at age eighty-eight. Between 1965 and 1981, the dapper white-suited father of New Journalism chronicled, in pyrotechnic prose, everything from Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters to the first American astronauts. And then, having revolutionized journalism with his kaleidoscopic yet rigorous reportage, he decided it was time to write novels. As he said in his Art of Fiction interview, “Practically everyone my age who wanted to write somehow got the impression in college that there was only one thing to write, which was a novel and that if you went into journalism, this was only a cup of coffee on the road to the final triumph. At some point you would move into a shack—it was always a shack for some reason—and write a novel. This would be your real métier.” With The Bonfire of the Vanities, Wolfe wrote a sprawling, quintessential magnum opus of New York in the eighties. His first two novels were runaway best sellers, and his success won him the bitter envy of Norman Mailer, John Updike, and John Irving, among others.

Tom Wolfe died yesterday at age eighty-eight. Between 1965 and 1981, the dapper white-suited father of New Journalism chronicled, in pyrotechnic prose, everything from Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters to the first American astronauts. And then, having revolutionized journalism with his kaleidoscopic yet rigorous reportage, he decided it was time to write novels. As he said in his Art of Fiction interview, “Practically everyone my age who wanted to write somehow got the impression in college that there was only one thing to write, which was a novel and that if you went into journalism, this was only a cup of coffee on the road to the final triumph. At some point you would move into a shack—it was always a shack for some reason—and write a novel. This would be your real métier.” With The Bonfire of the Vanities, Wolfe wrote a sprawling, quintessential magnum opus of New York in the eighties. His first two novels were runaway best sellers, and his success won him the bitter envy of Norman Mailer, John Updike, and John Irving, among others. Cusk has glimpsed the central truth of modern life: that sometimes it is as sublime as Homer, a sail full of wind with the sun overhead, and sometimes it is like an Ikea where all the couples are fighting. ‘I wonder what became of the human instinct for beauty,’ she writes in The Last Supper, ‘why it vanished so abruptly and so utterly, why our race should have fallen so totally out of sympathy with the earth.’ A line like this is both overwrought and what I think myself when I look at these scenes. Why must we live in these places? Why must these be our concerns? Why do I have to know what McDonald’s is? It is a dissociate age and she is a dissociate artist. She is like nothing so much as that high little YouTube child fresh from the dentist, strapped into a car going he knows not where, further and further from his own will. Where is real life to be found? Is this it?

Cusk has glimpsed the central truth of modern life: that sometimes it is as sublime as Homer, a sail full of wind with the sun overhead, and sometimes it is like an Ikea where all the couples are fighting. ‘I wonder what became of the human instinct for beauty,’ she writes in The Last Supper, ‘why it vanished so abruptly and so utterly, why our race should have fallen so totally out of sympathy with the earth.’ A line like this is both overwrought and what I think myself when I look at these scenes. Why must we live in these places? Why must these be our concerns? Why do I have to know what McDonald’s is? It is a dissociate age and she is a dissociate artist. She is like nothing so much as that high little YouTube child fresh from the dentist, strapped into a car going he knows not where, further and further from his own will. Where is real life to be found? Is this it? The first time Karl Ove Knausgaard saw Linda Bostrom, the Swedish writer he would later marry, he dropped everything he was holding. The first time she turned him down, he sliced his face to ribbons with a piece of broken glass. The first time they kissed, he fainted dead away.

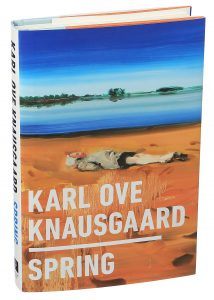

The first time Karl Ove Knausgaard saw Linda Bostrom, the Swedish writer he would later marry, he dropped everything he was holding. The first time she turned him down, he sliced his face to ribbons with a piece of broken glass. The first time they kissed, he fainted dead away. About a year ago, the theoretical chemist

About a year ago, the theoretical chemist  Arthur Brooks is president of the American Enterprise Institute, the center-right Washington think tank that has, amid a decade of turmoil inside the Republican Party, remained a sober, respected voice on matters of policy—while gradually shedding its George W. Bush-era reputation as a leading voice for pugnacious, interventionist foreign policy.

Arthur Brooks is president of the American Enterprise Institute, the center-right Washington think tank that has, amid a decade of turmoil inside the Republican Party, remained a sober, respected voice on matters of policy—while gradually shedding its George W. Bush-era reputation as a leading voice for pugnacious, interventionist foreign policy. On Monday, Ivanka Trump, Jared Kushner and other leading lights of the Trumpist right gathered in Israel to celebrate the relocation of the American Embassy to Jerusalem, a gesture widely seen as a slap in the face to Palestinians who envision East Jerusalem as their future capital.

On Monday, Ivanka Trump, Jared Kushner and other leading lights of the Trumpist right gathered in Israel to celebrate the relocation of the American Embassy to Jerusalem, a gesture widely seen as a slap in the face to Palestinians who envision East Jerusalem as their future capital. As a teenager, Keoni Gandall already was operating a cutting-edge research laboratory in his bedroom in Huntington Beach, Calif. While his friends were buying video games, he acquired more than a dozen pieces of equipment — a transilluminator, a centrifuge, two thermocyclers — in pursuit of a hobby that once was the province of white-coated Ph.D.’s in institutional labs. “I just wanted to clone DNA using my automated lab robot and feasibly make full genomes at home,” he said. Mr. Gandall was far from alone. In the past few years, so-called biohackers across the country have taken gene editing into their own hands. As the equipment becomes cheaper and the expertise in gene-editing techniques, mostly Crispr-Cas9, more widely shared, citizen-scientists are attempting to re-engineer DNA in surprising ways. Until now, the work has amounted to little more than D.I.Y. misfires. A year ago, a biohacker famously injected himself at a conference with modified DNA that he hoped would make him more muscular. (It did not.)

As a teenager, Keoni Gandall already was operating a cutting-edge research laboratory in his bedroom in Huntington Beach, Calif. While his friends were buying video games, he acquired more than a dozen pieces of equipment — a transilluminator, a centrifuge, two thermocyclers — in pursuit of a hobby that once was the province of white-coated Ph.D.’s in institutional labs. “I just wanted to clone DNA using my automated lab robot and feasibly make full genomes at home,” he said. Mr. Gandall was far from alone. In the past few years, so-called biohackers across the country have taken gene editing into their own hands. As the equipment becomes cheaper and the expertise in gene-editing techniques, mostly Crispr-Cas9, more widely shared, citizen-scientists are attempting to re-engineer DNA in surprising ways. Until now, the work has amounted to little more than D.I.Y. misfires. A year ago, a biohacker famously injected himself at a conference with modified DNA that he hoped would make him more muscular. (It did not.) We are still working on a few things, such as getting old posts from October 2017 up until April 2018 imported into the archives; fixing some issues with images not displaying correctly in a few old posts; problems with the daily emails not showing all posts; and a couple of other smaller issues.

We are still working on a few things, such as getting old posts from October 2017 up until April 2018 imported into the archives; fixing some issues with images not displaying correctly in a few old posts; problems with the daily emails not showing all posts; and a couple of other smaller issues.