Nicholas Pelham in More Intelligent Life:

When Muhammad bin Salman, Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince, visited New York earlier this year, the face of Ahmed Mater, the kingdom’s most celebrated artist, was beamed onto an enormous billboard in Times Square. In recent years, he has been feted at exhibitions in London, New York and Venice. He dominates the Saudi art scene so thoroughly that his peers struggle for attention. “He’s the only artist anyone writes about,” says one Saudi curator. In 2017 Mater was appointed as artistic director of the Prince’s cultural and educational foundation, entrusted to promote art across the kingdom and liberalise the school system. He plays a crucial role in the enormously ambitious plan for economic and social transformation, which aims to wean the country off reliance on oil revenues, strip down the power of clerics and dispel a reputation for medieval obscurantism and misogyny.

When Muhammad bin Salman, Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince, visited New York earlier this year, the face of Ahmed Mater, the kingdom’s most celebrated artist, was beamed onto an enormous billboard in Times Square. In recent years, he has been feted at exhibitions in London, New York and Venice. He dominates the Saudi art scene so thoroughly that his peers struggle for attention. “He’s the only artist anyone writes about,” says one Saudi curator. In 2017 Mater was appointed as artistic director of the Prince’s cultural and educational foundation, entrusted to promote art across the kingdom and liberalise the school system. He plays a crucial role in the enormously ambitious plan for economic and social transformation, which aims to wean the country off reliance on oil revenues, strip down the power of clerics and dispel a reputation for medieval obscurantism and misogyny.

Prince Muhammad has travelled the world to convince business leaders, tech titans and entertainment impresarios that Saudi Arabia is a place where both popular and high culture can flourish. For the first time in over 30 years, cinemas show films. For the first time ever, pop stars perform in concert halls. Mater has accompanied the prince on his pilgrimage as the epitome of the country’s artistic reawakening. When the Saudi Crown Prince met Xi Jinping, he brought Mater along and gave the Chinese president one of his paintings as a gift. The story behind Mater’s rise is more complex and ambiguous than his current pre-eminence suggests. It illuminates the unprecedented liberalisation that many of the country’s cultural elite are experiencing at the moment, as well as the compromises with power that they must still make. Mater did not reach the pinnacle without help. But some of his companions have fallen by the wayside. “Of course”, one Saudi artist tells me, “it wouldn’t have happened without Ashraf.”

More here.

I lost my heart from the moment I first saw it. Cill Rialaig is about as far west as you can go in Europe without falling off the edge. A magical place set in a wild landscape full of ghosts and memories, it’s a pre-famine village that clings to a steep slope, 300ft above the sea in Kerry, on the west coast of Ireland.

I lost my heart from the moment I first saw it. Cill Rialaig is about as far west as you can go in Europe without falling off the edge. A magical place set in a wild landscape full of ghosts and memories, it’s a pre-famine village that clings to a steep slope, 300ft above the sea in Kerry, on the west coast of Ireland. Scientists are preparing to create “miniature brains” that have been genetically engineered to contain Neanderthal DNA, in an unprecedented attempt to understand how humans differ from our closest relatives.

Scientists are preparing to create “miniature brains” that have been genetically engineered to contain Neanderthal DNA, in an unprecedented attempt to understand how humans differ from our closest relatives. It began inconspicuously, as so many riots do. People jostled in a sparsely policed public square lined with Jewish-owned shops. Worshippers idled after Easter services at the nearby Ciuflea Church, some drinking steadily once services ended, and teenagers as well as Jews—restless near the end of the long, eight-day Passover festival—were all rubbing shoulders. The weather was suddenly and blissfully temperate, dry after intermittent rain.

It began inconspicuously, as so many riots do. People jostled in a sparsely policed public square lined with Jewish-owned shops. Worshippers idled after Easter services at the nearby Ciuflea Church, some drinking steadily once services ended, and teenagers as well as Jews—restless near the end of the long, eight-day Passover festival—were all rubbing shoulders. The weather was suddenly and blissfully temperate, dry after intermittent rain. More

More  As a kid, I’d sometimes try to imagine what life would be like without a particular sense or part of my body, like with questions from the Would You Rather? game. Would you rather be deaf or blind? Would you rather have no legs or no arms? I’d try to erase the sound of my mom’s piano playing, the sight of the ground growing smaller as I soared on the tree swing in my backyard, or the feeling of playing basketball so hard my lungs might explode, but I just couldn’t. How could life go on without these sensations that were so tied to my idea of what it meant to be alive? I guess I’ve been feeling extra contemplative and nostalgic these days because I recently went through a pretty significant break-up…with my smartphone. My relationship with my phone was unhealthy in a lot of ways. I don’t remember exactly when I started needing to hold it during dinner or having to check Twitter before I got out of bed in the morning, but at some point I’d decided I couldn’t be without it. I’d started to notice just how often I was on my phone—and how unpleasant much of that time had become—when my daughter came along, and, just like that, time became infinitely more precious. So, I said goodbye. Now, as I reflect on the almost seven years my smartphone and I spent together, I’m starting to realize: What I had with my phone was largely physical.

As a kid, I’d sometimes try to imagine what life would be like without a particular sense or part of my body, like with questions from the Would You Rather? game. Would you rather be deaf or blind? Would you rather have no legs or no arms? I’d try to erase the sound of my mom’s piano playing, the sight of the ground growing smaller as I soared on the tree swing in my backyard, or the feeling of playing basketball so hard my lungs might explode, but I just couldn’t. How could life go on without these sensations that were so tied to my idea of what it meant to be alive? I guess I’ve been feeling extra contemplative and nostalgic these days because I recently went through a pretty significant break-up…with my smartphone. My relationship with my phone was unhealthy in a lot of ways. I don’t remember exactly when I started needing to hold it during dinner or having to check Twitter before I got out of bed in the morning, but at some point I’d decided I couldn’t be without it. I’d started to notice just how often I was on my phone—and how unpleasant much of that time had become—when my daughter came along, and, just like that, time became infinitely more precious. So, I said goodbye. Now, as I reflect on the almost seven years my smartphone and I spent together, I’m starting to realize: What I had with my phone was largely physical. Bae Suah seems to know that writing is a kind of time travel, and in each of these stories, brought deftly into English by Deborah Smith, the caroming and hyperlinking movements that characterize this traveling raise such questions as: what does it demand of me when I reach out to you? Where does my memory of you end and your reality begin? Why do I remember only that which I remember? And, as I write all of this, do I move any closer toward the answers?

Bae Suah seems to know that writing is a kind of time travel, and in each of these stories, brought deftly into English by Deborah Smith, the caroming and hyperlinking movements that characterize this traveling raise such questions as: what does it demand of me when I reach out to you? Where does my memory of you end and your reality begin? Why do I remember only that which I remember? And, as I write all of this, do I move any closer toward the answers? W

W For some readers, Howe’s work seems inscrutable or obtuse—obscure for the sake of difficulty as a kind of meaning in itself. Indeed, the poems stand awkwardly as individual works, and are best read as a volume. Taken as such, they offer a rewarding route to how one might construct a life—and a life’s work—from diving into language, the past, archival sources, and visual art. There is freedom in vastness and there is always more—more ideas, more ways of speaking and hearing, listening and knowing—to be found. Howe convinces us that intuited connections are real and possess a logic of their own, and that supposed breaks in continuity, in history or associations or sentences, are often the very place we should look to forge new connections. To stutter, to recombine or pull apart phonemes and line breaks, to wrench metaphors and to wrongly employ words, to cut and paste texts in images, shapes, lines, is to uncover so much possibility. Most critically, it is to admit and to relish the fact that we do not know all the ways in which we do not know—to be open to the grace of “not being in the no.”

For some readers, Howe’s work seems inscrutable or obtuse—obscure for the sake of difficulty as a kind of meaning in itself. Indeed, the poems stand awkwardly as individual works, and are best read as a volume. Taken as such, they offer a rewarding route to how one might construct a life—and a life’s work—from diving into language, the past, archival sources, and visual art. There is freedom in vastness and there is always more—more ideas, more ways of speaking and hearing, listening and knowing—to be found. Howe convinces us that intuited connections are real and possess a logic of their own, and that supposed breaks in continuity, in history or associations or sentences, are often the very place we should look to forge new connections. To stutter, to recombine or pull apart phonemes and line breaks, to wrench metaphors and to wrongly employ words, to cut and paste texts in images, shapes, lines, is to uncover so much possibility. Most critically, it is to admit and to relish the fact that we do not know all the ways in which we do not know—to be open to the grace of “not being in the no.” “I am glad you’ve read the Heart of D. tho’ of course it’s an awful fudge,” Joseph Conrad wrote to Roger Casement in late 1903. Casement, an Irish diplomat working for the British Foreign Office, had just returned to London from Belgium’s African colony, the Congo Free State, and was about to submit a report to Parliament detailing the existence of a vast system of slavery used to extract ivory and rubber. Looking to draw public attention to the atrocities, Casement traveled to the author’s home outside London to attempt to recruit him into the Congo Reform Association. Conrad was sympathetic: Africa, he told Casement, shared with Europe “the consciousness of the universe in which we live,” and it had been difficult for him to learn that the horrors he witnessed on his 1890 trip up the Congo River had only gotten worse. But he resisted playing the part of an on-the-spot authority and begged off joining Casement’s association. “I would help him but it is not in me,” Conrad later explained to a friend. “I am only a wretched novelist inventing wretched stories and not even up to that miserable game.”

“I am glad you’ve read the Heart of D. tho’ of course it’s an awful fudge,” Joseph Conrad wrote to Roger Casement in late 1903. Casement, an Irish diplomat working for the British Foreign Office, had just returned to London from Belgium’s African colony, the Congo Free State, and was about to submit a report to Parliament detailing the existence of a vast system of slavery used to extract ivory and rubber. Looking to draw public attention to the atrocities, Casement traveled to the author’s home outside London to attempt to recruit him into the Congo Reform Association. Conrad was sympathetic: Africa, he told Casement, shared with Europe “the consciousness of the universe in which we live,” and it had been difficult for him to learn that the horrors he witnessed on his 1890 trip up the Congo River had only gotten worse. But he resisted playing the part of an on-the-spot authority and begged off joining Casement’s association. “I would help him but it is not in me,” Conrad later explained to a friend. “I am only a wretched novelist inventing wretched stories and not even up to that miserable game.” The scientific

The scientific I would like to write about the bullshitization of academic life: that is, the degree to which those involved in teaching and academic management spend more and more of their time involved in tasks which they secretly — or not so secretly — believe to be entirely pointless.

I would like to write about the bullshitization of academic life: that is, the degree to which those involved in teaching and academic management spend more and more of their time involved in tasks which they secretly — or not so secretly — believe to be entirely pointless.

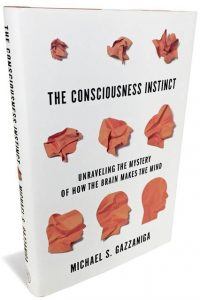

Three decades after being awarded the Nobel Prize for his discovery of DNA, Francis Crick wrote a book about consciousness, “The Astonishing Hypothesis: The Scientific Search for the Soul.” It was momentous: A world-renowned scientist had decided to directly confront the mind/body problem, the centuries-old challenge of reconciling the brain, a gelatinous mass of physical tissue, and human consciousness, the realm of emotion, volition and boundless imagination. Crick’s contention that the human mind arises from neurons in the brain rather than from an ineffable soul is perhaps less astonishing today, when this premise is nearly universally accepted among neuroscientists. But it still hints at something remarkable about Crick’s own mind. Why would a Nobel-winning scientist, already credited with discovering the secret of life, decide to switch gears and focus on an inquiry not only in a different field but so scientifically impenetrable as to have earned nicknames like “the hard problem” and “the last great mystery of science?” Crick answered this question with “what I called the gossip test: What you’re really interested in is what you gossip about. Gossip is things you’re interested in, but you don’t know much about.” In short: genuine curiosity.

Three decades after being awarded the Nobel Prize for his discovery of DNA, Francis Crick wrote a book about consciousness, “The Astonishing Hypothesis: The Scientific Search for the Soul.” It was momentous: A world-renowned scientist had decided to directly confront the mind/body problem, the centuries-old challenge of reconciling the brain, a gelatinous mass of physical tissue, and human consciousness, the realm of emotion, volition and boundless imagination. Crick’s contention that the human mind arises from neurons in the brain rather than from an ineffable soul is perhaps less astonishing today, when this premise is nearly universally accepted among neuroscientists. But it still hints at something remarkable about Crick’s own mind. Why would a Nobel-winning scientist, already credited with discovering the secret of life, decide to switch gears and focus on an inquiry not only in a different field but so scientifically impenetrable as to have earned nicknames like “the hard problem” and “the last great mystery of science?” Crick answered this question with “what I called the gossip test: What you’re really interested in is what you gossip about. Gossip is things you’re interested in, but you don’t know much about.” In short: genuine curiosity.

The idea that Debussy is one of music’s great revolutionaries still causes consternation. Many who consider themselves fans are aware only of the sensual timbres and mellifluous images in sound, often inspired by literary or visual allusion: water, air, wind, moonlight, at once static and mobile. How can music so apparently formless and exquisite also trigger innovation?

The idea that Debussy is one of music’s great revolutionaries still causes consternation. Many who consider themselves fans are aware only of the sensual timbres and mellifluous images in sound, often inspired by literary or visual allusion: water, air, wind, moonlight, at once static and mobile. How can music so apparently formless and exquisite also trigger innovation?