Lauren deLisa Coleman in Forbes:

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is nothing if not controversial. Whether the subject of scrutiny behind hair-raising advances in sex robots which was heavily reported the other week or the topic of the latest disgruntled executive voicing opinions about Elon Musk’s crusade against AI’s perceived perils, all eyes are on this new area in tech. While no one is yet absolutely sure of AI’s definitive path, one thing is certain. Value and expenditures pertaining to this area of emerging technology are on a definite upward curve. In fact, there is already a 70 percent growth in business value in AI just this far into 2018. This is clearly an area-to-watch. So, here’s how the rest of the year and beyond could take shape when it comes to the area of Artificial Intelligence. Derek Holt, a former IBM executive as well as former Managing Director of Business Development at Startup America Partnership, a public-private partnership with the White House believes the biggest play with be in healthcare:

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is nothing if not controversial. Whether the subject of scrutiny behind hair-raising advances in sex robots which was heavily reported the other week or the topic of the latest disgruntled executive voicing opinions about Elon Musk’s crusade against AI’s perceived perils, all eyes are on this new area in tech. While no one is yet absolutely sure of AI’s definitive path, one thing is certain. Value and expenditures pertaining to this area of emerging technology are on a definite upward curve. In fact, there is already a 70 percent growth in business value in AI just this far into 2018. This is clearly an area-to-watch. So, here’s how the rest of the year and beyond could take shape when it comes to the area of Artificial Intelligence. Derek Holt, a former IBM executive as well as former Managing Director of Business Development at Startup America Partnership, a public-private partnership with the White House believes the biggest play with be in healthcare:

Wellness Trend Data and Associated Care — “Gone will be the days of annual or bi-annual physicals as more and more of our wellness will be digitized,” explains Holt. “Both AI and Machine Learning will aid and empower the traditional medical field to unlock new preventative and early intervention care.”

Technology-Aided Caregivers — “Over the next 30 years, the number of caregivers available to take care of older adults and individual s living with disabilities is expected to decrease,” he continues. “Given this shortage, we’ll begin to see technology-aided caregivers emerge to help with day-to-day tasks that have become harder for older adults and individuals living with disabilities to complete.”

More here.

D

D BLVR: Yeah, and it made me wonder about your dreams—do you have any recurring dreams?

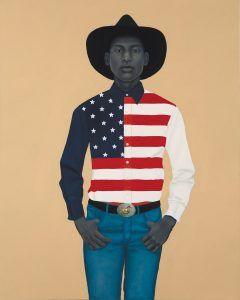

BLVR: Yeah, and it made me wonder about your dreams—do you have any recurring dreams? Grant Wood wanted to make art American. As with so many attempts to make things American, what this meant was distilling a particular region into the essence of the United States. New England and the Deep South are strong contenders, but the Midwest is perhaps the most plausibly all-American region. The visual and cultural tropes of the Midwest are the commonplaces of American kitsch—corn fields, barns, apple pie, churches, Main Street. By choosing to remain in his native Iowa, Wood was well positioned to do what he wanted, without having to forego success. The current Wood retrospective on view at the Whitney (closing June 10th) is hardly the first time his work has received sustained attention from the highest levels of the American art world. The Whitney itself held its last retrospective in 1983, and during Wood’s lifetime he was arguably the most famous artist in the United States. The current show acknowledges that one of Wood’s paintings dominates all other. The exhibition simply uses the name of American Gothic, adding, appropriately, “and other fables” after the obligatory colon.

Grant Wood wanted to make art American. As with so many attempts to make things American, what this meant was distilling a particular region into the essence of the United States. New England and the Deep South are strong contenders, but the Midwest is perhaps the most plausibly all-American region. The visual and cultural tropes of the Midwest are the commonplaces of American kitsch—corn fields, barns, apple pie, churches, Main Street. By choosing to remain in his native Iowa, Wood was well positioned to do what he wanted, without having to forego success. The current Wood retrospective on view at the Whitney (closing June 10th) is hardly the first time his work has received sustained attention from the highest levels of the American art world. The Whitney itself held its last retrospective in 1983, and during Wood’s lifetime he was arguably the most famous artist in the United States. The current show acknowledges that one of Wood’s paintings dominates all other. The exhibition simply uses the name of American Gothic, adding, appropriately, “and other fables” after the obligatory colon. Asad Raza: In 2015, Nicola Lees invited me to do something for the Ljubljana Biennial, and I had a thought of the school, especially experimental pedagogy, as an interesting thing. I asked Jeff and Graham to collaborate on this, as they probably know the subject much, much better than I do. But I was interested in making some formal conditions, let’s say, under which an experimental school could flourish inside an exhibition. I think of these as sketches for an institution that would be up to the 21st century somehow, a multivalent cultural institution that could do exhibitions, that would have education, but the education wouldn’t function in the way that education departments do right now, you know?

Asad Raza: In 2015, Nicola Lees invited me to do something for the Ljubljana Biennial, and I had a thought of the school, especially experimental pedagogy, as an interesting thing. I asked Jeff and Graham to collaborate on this, as they probably know the subject much, much better than I do. But I was interested in making some formal conditions, let’s say, under which an experimental school could flourish inside an exhibition. I think of these as sketches for an institution that would be up to the 21st century somehow, a multivalent cultural institution that could do exhibitions, that would have education, but the education wouldn’t function in the way that education departments do right now, you know? If you bring together two enigmas, do you get a bigger enigma, or do they cancel each other out, like multiplied negative numbers, to produce clarity? The latter, I hope, as I take on Wittgenstein and mysticism.

If you bring together two enigmas, do you get a bigger enigma, or do they cancel each other out, like multiplied negative numbers, to produce clarity? The latter, I hope, as I take on Wittgenstein and mysticism. As misinformation weapons go, fake news is sort of like a cannon: noisy and provocative. Innuendo is like a dirty bomb — invisible, toxic and lingering. I became more aware of the misleading uses of innuendo after I spoke with linguistics professor Andrew Kehler during the run-up to the 2016 election.

As misinformation weapons go, fake news is sort of like a cannon: noisy and provocative. Innuendo is like a dirty bomb — invisible, toxic and lingering. I became more aware of the misleading uses of innuendo after I spoke with linguistics professor Andrew Kehler during the run-up to the 2016 election. After graduation, Thurman settled in Harlem in the 1920s and became a leading (and legendary) figure in the Harlem Renaissance—part of the “niggerati,” as Zora Neale Hurston famously called this influential group of intellectuals and artists. Working with A. Philip Randolph, Thurman became an editor at The Messenger, a political and literary journal, and in 1926 he co-founded, with Hurston, Hughes, Aaron Douglas, Gwendolyn Bennett, and Bruce Nugent, a bold and innovative publication called Fire!!, which featured the work of younger artists but was disliked by the black middle class because of its candid presentation of black life. In 1929, Thurman collaborated with the white playwright William Jourdan Rapp to write and produce Harlem, which ran for 93 performances and became “the first successful play written entirely or in part by a Negro to appear on Broadway.” Thurman believed that African Americans could overcome racial barriers, but he experienced countless incidents of racism during his short life.

After graduation, Thurman settled in Harlem in the 1920s and became a leading (and legendary) figure in the Harlem Renaissance—part of the “niggerati,” as Zora Neale Hurston famously called this influential group of intellectuals and artists. Working with A. Philip Randolph, Thurman became an editor at The Messenger, a political and literary journal, and in 1926 he co-founded, with Hurston, Hughes, Aaron Douglas, Gwendolyn Bennett, and Bruce Nugent, a bold and innovative publication called Fire!!, which featured the work of younger artists but was disliked by the black middle class because of its candid presentation of black life. In 1929, Thurman collaborated with the white playwright William Jourdan Rapp to write and produce Harlem, which ran for 93 performances and became “the first successful play written entirely or in part by a Negro to appear on Broadway.” Thurman believed that African Americans could overcome racial barriers, but he experienced countless incidents of racism during his short life. What would

What would  Refashioning history to include its countless heroines is essential work, long overdue. But what of the future? Will these books, as the introduction to Herstory implores, truly encourage young girls to “take inspiration from these . . . amazing women and girls and shake things up!”? Perhaps. Last year, Science magazine published research investigating the age at which girls begin to think that they are less intellectually brilliant than boys. The study involved reading two stories to children between the ages of five and seven. One, they explained, was about a “really, really smart” person; the other, a “really, really nice” one. Afterwards, the children were asked which was about a girl, and which about a boy. At five, the boys were sure the “really, really smart” character was a boy, the girls equally adamant it was a girl. By six, however, something had changed. In the space of twelve months, the girls had become 20 per cent less likely to think that a clever character could share their gender. According to Dario Cvencek, a research scientist at the University of Washington, the results would be more depressing still had the hero of the book been a mathematician. Children absorb the gender prejudices on display in their environments and reading matter from the age of around five, he says – especially the idea that girls don’t do numbers. The stereotypes portrayed in their reading material become their own stereotypes and, worse still, the limits of their ambitions. The most powerful way to combat this, as the psychologist Nilanjana Dasgupta has found, is through providing successful female role models to small girls before the disease sets in, as a form of “stereotype inoculation”.

Refashioning history to include its countless heroines is essential work, long overdue. But what of the future? Will these books, as the introduction to Herstory implores, truly encourage young girls to “take inspiration from these . . . amazing women and girls and shake things up!”? Perhaps. Last year, Science magazine published research investigating the age at which girls begin to think that they are less intellectually brilliant than boys. The study involved reading two stories to children between the ages of five and seven. One, they explained, was about a “really, really smart” person; the other, a “really, really nice” one. Afterwards, the children were asked which was about a girl, and which about a boy. At five, the boys were sure the “really, really smart” character was a boy, the girls equally adamant it was a girl. By six, however, something had changed. In the space of twelve months, the girls had become 20 per cent less likely to think that a clever character could share their gender. According to Dario Cvencek, a research scientist at the University of Washington, the results would be more depressing still had the hero of the book been a mathematician. Children absorb the gender prejudices on display in their environments and reading matter from the age of around five, he says – especially the idea that girls don’t do numbers. The stereotypes portrayed in their reading material become their own stereotypes and, worse still, the limits of their ambitions. The most powerful way to combat this, as the psychologist Nilanjana Dasgupta has found, is through providing successful female role models to small girls before the disease sets in, as a form of “stereotype inoculation”.

It is not uncommon that I lie about what I do for a living. When meeting strangers, basic introductions quickly turn into conversational quicksand for me. Whether posed for identification, categorization, assessment of social status, or to fill an empty conversation, inquiries about work are difficult to avoid. I know that such questions are innocent attempts to situate me somewhere in the atmosphere; we use the occupational compass to direct us toward an identifiable point in each other’s lives. I know this, and yet the job question, when it comes, often has me squirming for answers. My eyes dart away from the pair in front of me expecting a straightforward reply.

It is not uncommon that I lie about what I do for a living. When meeting strangers, basic introductions quickly turn into conversational quicksand for me. Whether posed for identification, categorization, assessment of social status, or to fill an empty conversation, inquiries about work are difficult to avoid. I know that such questions are innocent attempts to situate me somewhere in the atmosphere; we use the occupational compass to direct us toward an identifiable point in each other’s lives. I know this, and yet the job question, when it comes, often has me squirming for answers. My eyes dart away from the pair in front of me expecting a straightforward reply. A few months into a cushy postdoctoral fellowship at Princeton, where the walls were a soothing yellow and poached salmon was a staple, it dawned on me that I could reasonably be considered an arsehole. This wasn’t the first time the thought had occurred to me: after all, I am the kind of Brit who insists on the difference between a donkey, otherwise known as an ass, and a backside, otherwise known as an arse. But on this occasion my reflection was prompted not by looking in the mirror or by hearing a recording of my voice but by the experience of being a philosopher in a non-philosophical setting. Calling yourself a philosopher already makes you sound a bit of an arse, but the fact remains that I have spent most of my professional life studying, discussing, writing and teaching philosophy—and it is this, I submit, that has made me liable to appear a right royal arsehole.

A few months into a cushy postdoctoral fellowship at Princeton, where the walls were a soothing yellow and poached salmon was a staple, it dawned on me that I could reasonably be considered an arsehole. This wasn’t the first time the thought had occurred to me: after all, I am the kind of Brit who insists on the difference between a donkey, otherwise known as an ass, and a backside, otherwise known as an arse. But on this occasion my reflection was prompted not by looking in the mirror or by hearing a recording of my voice but by the experience of being a philosopher in a non-philosophical setting. Calling yourself a philosopher already makes you sound a bit of an arse, but the fact remains that I have spent most of my professional life studying, discussing, writing and teaching philosophy—and it is this, I submit, that has made me liable to appear a right royal arsehole. Few subjects have afforded more room for doubt, or caused more harm through false certainty, than heredity. In She Has Her Mother’s Laugh, an illuminating survey of the concept through history, science writer Carl Zimmer shows that scientists have often clung to travesties of the truth — and that we are still in danger of doing so.

Few subjects have afforded more room for doubt, or caused more harm through false certainty, than heredity. In She Has Her Mother’s Laugh, an illuminating survey of the concept through history, science writer Carl Zimmer shows that scientists have often clung to travesties of the truth — and that we are still in danger of doing so. If you wanted to feel the full force of the intellectual whirlpool that is American politics in 2018, the place to go on April 2 was the Village Underground, a nightclub beneath West 3rd Street, where Alan Dershowitz, the longtime Harvard Law professor and civil liberties lion, was debating the future of American democracy on the side of President Donald Trump.

If you wanted to feel the full force of the intellectual whirlpool that is American politics in 2018, the place to go on April 2 was the Village Underground, a nightclub beneath West 3rd Street, where Alan Dershowitz, the longtime Harvard Law professor and civil liberties lion, was debating the future of American democracy on the side of President Donald Trump. Of course, I am happy for those I have never met. Prince Henry (Harry), who lost his mother at twelve—lost her to monarchy, and the occasionally murderous intrusions that now define it—found a woman to hold him and, I think, he laid his heart before her. She was touched by him—Harry is a lonely prince, a semi-mythical being—and she picked it up. It looked real. I hope it is real, even as I resent having an opinion on a stranger’s love. That this was televised in an event as emotionally grasping as the funeral that incited the very need we thought we saw sated on Saturday should be obvious, but it was not mentioned. It should be the final, impolite word on the royal wedding.

Of course, I am happy for those I have never met. Prince Henry (Harry), who lost his mother at twelve—lost her to monarchy, and the occasionally murderous intrusions that now define it—found a woman to hold him and, I think, he laid his heart before her. She was touched by him—Harry is a lonely prince, a semi-mythical being—and she picked it up. It looked real. I hope it is real, even as I resent having an opinion on a stranger’s love. That this was televised in an event as emotionally grasping as the funeral that incited the very need we thought we saw sated on Saturday should be obvious, but it was not mentioned. It should be the final, impolite word on the royal wedding. Read a few lines of a talented poet charged with God—from the otherworldly lines of Gerard Manley Hopkins on forward to Akbar himself—and you see what faith can do to language. There’s a lift. A particular lean. A curious mixture of confidence and humility. A strangeness borne of awe. Peter O’Leary’s book of criticism,

Read a few lines of a talented poet charged with God—from the otherworldly lines of Gerard Manley Hopkins on forward to Akbar himself—and you see what faith can do to language. There’s a lift. A particular lean. A curious mixture of confidence and humility. A strangeness borne of awe. Peter O’Leary’s book of criticism,