Kenan Malik in The Guardian:

Two reports last week exposed both the changing character of the labour market and the degree to which the power of the organised working class has eroded.

Two reports last week exposed both the changing character of the labour market and the degree to which the power of the organised working class has eroded.

The Office for National Statistics revealed that there were just 79 strikes (or, more specifically, stoppages) last year, the lowest figure since records began in 1891. Just 33,000 workers were involved in labour disputes, the lowest number since 1893. Victorian conditions have returned in more ways than one.

It’s not just the number of strikes that has fallen. Trade union membership has too. The latest figures from the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy show that just 23.2% of employees were unionised in 2017, a half that of the late 1970s.

The fall has been greatest among the young. The proportion of union members under 50 has fallen over the past 20 years, while that above 50 has increased.

Strikingly, too, unions have increasingly become clubs for professionals. One in five employees works in professional jobs, but they make up almost 40% of union members. These days, you are twice as likely to be unionised if you have a degree than if you have no qualifications. It’s a far cry from the old image of the trade unionist as an industrial worker. Unions have not just shrunk – their very character has changed. Like politics, trade unionism has become more professional and technocratic.

More here.

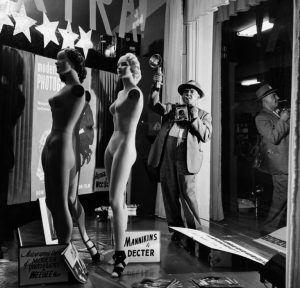

Usher Fellig was a greenhorn, a hungry shtetl child from eastern Europe who spoke no English. When he came through Ellis Island in 1909, at ten years old, he reinvented himself, as so many immigrants do. In his first years in New York, Usher became Arthur, a Lower East Side street kid who was eager to get out of what he called “the lousy tenements,” earn a living, impress girls, make a splash. He had turned his name (slightly) less Jewish and his identity (somewhat) more American, as much as he could make it. As a young man, he was shy, awkward, broke, and unpolished, and at fourteen, he became a seventh-grade dropout. He was also smart, ambitious, funny, and (as he and then his fellow New Yorkers and eventually the world discovered) enormously expressive when you put a camera in his hands.

Usher Fellig was a greenhorn, a hungry shtetl child from eastern Europe who spoke no English. When he came through Ellis Island in 1909, at ten years old, he reinvented himself, as so many immigrants do. In his first years in New York, Usher became Arthur, a Lower East Side street kid who was eager to get out of what he called “the lousy tenements,” earn a living, impress girls, make a splash. He had turned his name (slightly) less Jewish and his identity (somewhat) more American, as much as he could make it. As a young man, he was shy, awkward, broke, and unpolished, and at fourteen, he became a seventh-grade dropout. He was also smart, ambitious, funny, and (as he and then his fellow New Yorkers and eventually the world discovered) enormously expressive when you put a camera in his hands. The show’s visual grammar reflects this anxiety and paranoia. Murai’s choice to use film is a potent reminder that this is still fiction, but the choice makes it all the more real—not only because film adds texture, but also because when the celluloid occasionally pops, that jumpiness contributes to the show’s overall tone. Late night, after the strip club gets out, there’s an Edward Hopper tableau of small, illuminated spaces engulfed in darkness. The introduction of magical realism is straight out of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, only Atlanta is a black Macondo made famous by Magic City, and instead of a woman floating up into the sky, there’s a disappearing club promoter and an invisible sports car.

The show’s visual grammar reflects this anxiety and paranoia. Murai’s choice to use film is a potent reminder that this is still fiction, but the choice makes it all the more real—not only because film adds texture, but also because when the celluloid occasionally pops, that jumpiness contributes to the show’s overall tone. Late night, after the strip club gets out, there’s an Edward Hopper tableau of small, illuminated spaces engulfed in darkness. The introduction of magical realism is straight out of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, only Atlanta is a black Macondo made famous by Magic City, and instead of a woman floating up into the sky, there’s a disappearing club promoter and an invisible sports car. The credit for arguably the best idea ever for a White House event goes to the fertile brain of Richard Goodwin. In a note to Jacqueline Kennedy in November 1961, the president’s aide was to the point: “How about a dinner for the American winners of the Nobel Prize?” Within six months, the largest social event of the New Frontier had occurred. By contemporary accounts, it was a smash. And it has resonated through the decades as a symbol of what that “one brief, shining moment” was capable of on its best days, and of the impact a White House can have on American culture and the creative minds who inhabit it. Comparisons to the disgusting atmosphere of the present are obvious. John Kennedy was pleased, but not entirely. According to his and his wife’s friend, the artist William Walton, the president called him later to complain about the woman who had been seated on his right, Ernest Hemingway’s fourth wife and widow of a year, Mary, who gave him repeated guff for his Cuba policy; Kennedy was more impressed by the dignified woman on his left, Katherine Marshall, the widow of George C. Marshall, the World War II commander and architect of the postwar reconstruction plan that bore his name. “Well, your friend Mary Hemingway is the biggest bore I’d had for a long time,” Walton quoted JFK as saying. “If I hadn’t had Mrs. Marshall I would have had a terrible night.” Walton couldn’t say much in reply: Mary Hemingway was right next to him in his Georgetown home when the call came.

The credit for arguably the best idea ever for a White House event goes to the fertile brain of Richard Goodwin. In a note to Jacqueline Kennedy in November 1961, the president’s aide was to the point: “How about a dinner for the American winners of the Nobel Prize?” Within six months, the largest social event of the New Frontier had occurred. By contemporary accounts, it was a smash. And it has resonated through the decades as a symbol of what that “one brief, shining moment” was capable of on its best days, and of the impact a White House can have on American culture and the creative minds who inhabit it. Comparisons to the disgusting atmosphere of the present are obvious. John Kennedy was pleased, but not entirely. According to his and his wife’s friend, the artist William Walton, the president called him later to complain about the woman who had been seated on his right, Ernest Hemingway’s fourth wife and widow of a year, Mary, who gave him repeated guff for his Cuba policy; Kennedy was more impressed by the dignified woman on his left, Katherine Marshall, the widow of George C. Marshall, the World War II commander and architect of the postwar reconstruction plan that bore his name. “Well, your friend Mary Hemingway is the biggest bore I’d had for a long time,” Walton quoted JFK as saying. “If I hadn’t had Mrs. Marshall I would have had a terrible night.” Walton couldn’t say much in reply: Mary Hemingway was right next to him in his Georgetown home when the call came. How easy it would be,

How easy it would be,  The 20th century was a remarkably productive one for physics. First, Albert Einstein’s

The 20th century was a remarkably productive one for physics. First, Albert Einstein’s  Ask people to name the key minds that have shaped America’s burst of radical right-wing attacks on working conditions, consumer rights and public services, and they will typically mention figures like free market-champion Milton Friedman, libertarian guru Ayn Rand, and laissez-faire economists Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises.

Ask people to name the key minds that have shaped America’s burst of radical right-wing attacks on working conditions, consumer rights and public services, and they will typically mention figures like free market-champion Milton Friedman, libertarian guru Ayn Rand, and laissez-faire economists Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises. It is election season in

It is election season in  What’s especially impressive about this adaptation is not only that it is enjoyable, but that it directly confronts the problem of addiction without glamorising it. Other dramas about womanising addicts—for example Mad Men or Californication—tend to focus on the debauchery as much as the interior consequences; this makes it easy for the viewer to avoid processing the trauma. Watching Mad Men’s Don Draper pour himself yet another glass of whiskey, having hit yet another rock bottom, doesn’t quell the desire (provoked by the sexy depiction of the world of the programme) to reach for a cigarette and a whiskey yourself. Even in Channel 4’s Sherlock, the detective’s opium habit is seen as a facet of his genius: a necessary method for him to open the doors of perception. There is something beguiling and (literally) intoxicating about watching someone dance so close to the cliff edge. Indulging this behaviour onscreen can make it seem attractive rather than repellent.

What’s especially impressive about this adaptation is not only that it is enjoyable, but that it directly confronts the problem of addiction without glamorising it. Other dramas about womanising addicts—for example Mad Men or Californication—tend to focus on the debauchery as much as the interior consequences; this makes it easy for the viewer to avoid processing the trauma. Watching Mad Men’s Don Draper pour himself yet another glass of whiskey, having hit yet another rock bottom, doesn’t quell the desire (provoked by the sexy depiction of the world of the programme) to reach for a cigarette and a whiskey yourself. Even in Channel 4’s Sherlock, the detective’s opium habit is seen as a facet of his genius: a necessary method for him to open the doors of perception. There is something beguiling and (literally) intoxicating about watching someone dance so close to the cliff edge. Indulging this behaviour onscreen can make it seem attractive rather than repellent. Around the time that Imasuen was getting yelled at by his mother, the author of “Purple Hibiscus,” Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who is now regarded as one of the most vital and original novelists of her generation, was living in a poky apartment in Baltimore, writing the last sections of her second book. She was twenty-six. “Purple Hibiscus,” published the previous fall, had established her reputation as an up-and-coming writer, but she was not yet well known.

Around the time that Imasuen was getting yelled at by his mother, the author of “Purple Hibiscus,” Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who is now regarded as one of the most vital and original novelists of her generation, was living in a poky apartment in Baltimore, writing the last sections of her second book. She was twenty-six. “Purple Hibiscus,” published the previous fall, had established her reputation as an up-and-coming writer, but she was not yet well known. Heron the critic was also one of the figures responsible for introducing the American abstract expressionists to a British audience. Although he was later to accuse Pollock, De Kooning et al (but not Rothko) of cultural imperialism and not being painterly enough, the scale of their pictures, their rhythm, saturated palette and insistence that each part of the canvas was as important as every other, had a profound effect on him. Heron believed that, “Painting is thinking with one’s hand; or with one’s arm; in fact with one’s whole body,” and the epic AbEx works represented his aphorism in action.

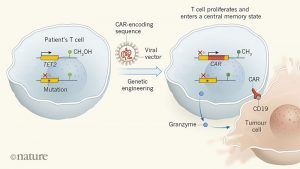

Heron the critic was also one of the figures responsible for introducing the American abstract expressionists to a British audience. Although he was later to accuse Pollock, De Kooning et al (but not Rothko) of cultural imperialism and not being painterly enough, the scale of their pictures, their rhythm, saturated palette and insistence that each part of the canvas was as important as every other, had a profound effect on him. Heron believed that, “Painting is thinking with one’s hand; or with one’s arm; in fact with one’s whole body,” and the epic AbEx works represented his aphorism in action. The use of genetically engineered immune cells to target tumours is one of the most exciting current developments in cancer treatment. In this approach, T cells are taken from a patient and modified in vitro by inserting an engineered version of a gene that encodes a receptor protein. The receptor, known as a chimaeric antigen receptors (CAR), directs the engineered cell, called a CAR T cell, to the patient’s tumour when the cell is transferred back into the body. This therapy can be highly effective for tumours that express the protein CD19, such as B-cell acute leukaemias

The use of genetically engineered immune cells to target tumours is one of the most exciting current developments in cancer treatment. In this approach, T cells are taken from a patient and modified in vitro by inserting an engineered version of a gene that encodes a receptor protein. The receptor, known as a chimaeric antigen receptors (CAR), directs the engineered cell, called a CAR T cell, to the patient’s tumour when the cell is transferred back into the body. This therapy can be highly effective for tumours that express the protein CD19, such as B-cell acute leukaemias

Critics of Goldman Sachs love to say the investment bank highlights the failures of everything from capitalism and neoliberalism to democracy and socialism. Millions of words have been written depicting Goldman as the central villain of the Great Recession, yet little has been said about their most egregious sin: their lobby art. In 2010, Goldman Sachs paid $5 million for a custom-made Julie Meheretu mural for their New York headquarters. Expectations are low for corporate lobby art, yet Meheretu’s giant painting is remarkably ugly—so ugly that it helps us sift through a decade of Goldman criticisms and get to the heart of what is wrong with the elites of our country.

Critics of Goldman Sachs love to say the investment bank highlights the failures of everything from capitalism and neoliberalism to democracy and socialism. Millions of words have been written depicting Goldman as the central villain of the Great Recession, yet little has been said about their most egregious sin: their lobby art. In 2010, Goldman Sachs paid $5 million for a custom-made Julie Meheretu mural for their New York headquarters. Expectations are low for corporate lobby art, yet Meheretu’s giant painting is remarkably ugly—so ugly that it helps us sift through a decade of Goldman criticisms and get to the heart of what is wrong with the elites of our country. In

In