From Y Combinator:

John Preskill is a theoretical physicist and the Richard P. Feynman Professor of Theoretical Physics at Caltech.

John Preskill is a theoretical physicist and the Richard P. Feynman Professor of Theoretical Physics at Caltech.

He once won a bet with Steven Hawking, which as he writes made him “briefly almost famous.” John and Kip Thorne bet that singularities could exist outside of black holes and after six years Hawking conceded that they were possible in very special, “nongeneric” conditions.

In this episode we cover what John’s been focusing on for years: quantum information, quantum computing, and quantum error correction.

What was the revelation that made scientists and physicists think that a quantum computer could exist?

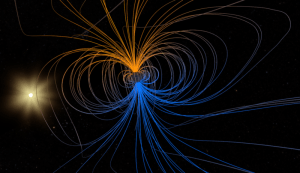

John Preskill – The idea caught on about 10 years later when Peter Shore made the suggestion that we could solve problems which don’t seem to have anything to do with physics, which are really things about numbers like finding the prime factors of a big integer. That caused a lot of excitement in part, because the implications for cryptography are a big disturbing. But then physicists, good physicists– Started to consider, can we really build this thing?

Some concluded and argued fairly cogently that no, you couldn’t because of this difficulty that it’s so hard to isolate systems from the environment well enough for them to behave quantumly. It took a few years for that to sort out sort of at the theoretical level. In the mid ’90s we developed a theory called quantum error correction. It’s about how to encode the quantum state that you’d like to protect in such a clever way that even if there are some interactions with the environment that you can’t control, it still stays robust. At first, that was just kind of a theorist fantasy. It was a little too far ahead of the technology, but 20 years later, the technology is catching up. Now this idea of quantum error correction has become something you could do in the lab.

More here.

In

In  To pick up on almost any story in the news these days—political, financial, sexual, or environmental—is to be informed in the opening monologue that the rule of law is vanished from the face of the American earth. So sayeth

To pick up on almost any story in the news these days—political, financial, sexual, or environmental—is to be informed in the opening monologue that the rule of law is vanished from the face of the American earth. So sayeth  Marco Roth in n+1:

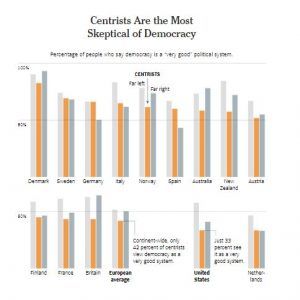

Marco Roth in n+1: David Adler in the NYT:

David Adler in the NYT: Andreas Wimmer in Aeon:

Andreas Wimmer in Aeon: Zach Carter in The Huffington Post:

Zach Carter in The Huffington Post: Writers of genuine originality are always divisive. Roth alienated not just the occasional reader but entire communities, reviled, first, by world Jewry, and later by world feminism. This choric hostility was in both cases essentially socio-cultural, and not literary. You can understand the historical uneasiness, but World Jewry got it wrong about Roth, a proud Jew as well as a proud American. And the feminist objection is impetuously sweeping; it detects no distance between Roth and his (often deplorable) narrators. Besides, if you outlaw misogyny as a subject, then you outlaw King Lear, and much else.

Writers of genuine originality are always divisive. Roth alienated not just the occasional reader but entire communities, reviled, first, by world Jewry, and later by world feminism. This choric hostility was in both cases essentially socio-cultural, and not literary. You can understand the historical uneasiness, but World Jewry got it wrong about Roth, a proud Jew as well as a proud American. And the feminist objection is impetuously sweeping; it detects no distance between Roth and his (often deplorable) narrators. Besides, if you outlaw misogyny as a subject, then you outlaw King Lear, and much else. In 2010, just before Thanksgiving, American foreign-policy makers flew into a panic. The United States government had gotten word that an outfit called WikiLeaks was preparing to release an enormous cache of secret diplomatic cables, in coordination with teams of journalists from this and other newspapers. At the time, I was a policy hand in the State Department. It fell to me and my colleagues to dutifully craft apologies on behalf of our bosses, whose sensitive communications and private insults — speculation about, say, a foreign leader’s mental aptitude or mysterious wealth — were about to become public. They, meanwhile, confronted weightier concerns, scrambling to anticipate the coming fallout. Would missions and sources be compromised? Would activists be exposed to persecution? Would anyone ever talk to American officials again? Almost no one, however, anticipated what would prove to be one of the more lasting consequences of the leak: surprised admiration for American diplomats. “My personal opinion of the State Department has gone up several notches,” the British historian and journalist

In 2010, just before Thanksgiving, American foreign-policy makers flew into a panic. The United States government had gotten word that an outfit called WikiLeaks was preparing to release an enormous cache of secret diplomatic cables, in coordination with teams of journalists from this and other newspapers. At the time, I was a policy hand in the State Department. It fell to me and my colleagues to dutifully craft apologies on behalf of our bosses, whose sensitive communications and private insults — speculation about, say, a foreign leader’s mental aptitude or mysterious wealth — were about to become public. They, meanwhile, confronted weightier concerns, scrambling to anticipate the coming fallout. Would missions and sources be compromised? Would activists be exposed to persecution? Would anyone ever talk to American officials again? Almost no one, however, anticipated what would prove to be one of the more lasting consequences of the leak: surprised admiration for American diplomats. “My personal opinion of the State Department has gone up several notches,” the British historian and journalist  TAO LIN’S EIGHTH BOOK, Trip, is his best yet, and it’s all thanks to drugs. Well, perhaps not entirely thanks to drugs. With exercise comes mastery, or at least competence, and Lin has been practicing his idiosyncratic craft for over a decade. His first book was published in 2006, when he was twenty-three; improvement during the intervening years may have been inevitable. But Lin—whose authorial voice, notoriously, is so assiduously literal that it sometimes seems transcribed from a robot failing a Turing test—has never been more creative, precise, or inspired than when he details psychedelics-begotten behavior and theories. The behavior is mostly his own, while the theories are often borrowed from Terence McKenna, the late psilocybin advocate whose YouTube videos started Lin down the path to revitalization. While studying McKenna, Lin began to make radical adjustments to his daily drug routines, which in turn radically affected his mind-set.

TAO LIN’S EIGHTH BOOK, Trip, is his best yet, and it’s all thanks to drugs. Well, perhaps not entirely thanks to drugs. With exercise comes mastery, or at least competence, and Lin has been practicing his idiosyncratic craft for over a decade. His first book was published in 2006, when he was twenty-three; improvement during the intervening years may have been inevitable. But Lin—whose authorial voice, notoriously, is so assiduously literal that it sometimes seems transcribed from a robot failing a Turing test—has never been more creative, precise, or inspired than when he details psychedelics-begotten behavior and theories. The behavior is mostly his own, while the theories are often borrowed from Terence McKenna, the late psilocybin advocate whose YouTube videos started Lin down the path to revitalization. While studying McKenna, Lin began to make radical adjustments to his daily drug routines, which in turn radically affected his mind-set. Humans have long trapped animals in cages, nets and snares, but the tangled webs of vanity, curiosity, cruelty and fear we cast over other creatures may be even more perilous. We see our virtues and vices reflected in animals — hardworking beavers, indolent sloths, innocent lambs, greedy vultures — through a glass darkly. But these well-worn clichés blind us to a world far more dazzling and varied, according to Lucy Cooke, the acclaimed zoology-trained author and documentary filmmaker, in her new book, “The Truth About Animals.” As she writes, “Painting the animal kingdom with our artificial ethical brush denies us the astonishing diversity of life, in all of its blood-drinking, sibling-eating, corpse-shagging glory.” (Yes, corpse shagging. The penguin portion is not for the faint of heart.)

Humans have long trapped animals in cages, nets and snares, but the tangled webs of vanity, curiosity, cruelty and fear we cast over other creatures may be even more perilous. We see our virtues and vices reflected in animals — hardworking beavers, indolent sloths, innocent lambs, greedy vultures — through a glass darkly. But these well-worn clichés blind us to a world far more dazzling and varied, according to Lucy Cooke, the acclaimed zoology-trained author and documentary filmmaker, in her new book, “The Truth About Animals.” As she writes, “Painting the animal kingdom with our artificial ethical brush denies us the astonishing diversity of life, in all of its blood-drinking, sibling-eating, corpse-shagging glory.” (Yes, corpse shagging. The penguin portion is not for the faint of heart.) As well as documenting personal misery, this book is a portrait of a society that has forgotten what it is for. Our economies have become “vast engines for producing nonsense”. Utopian ideals have been abandoned on all sides, replaced by praise for “hardworking families”. The rightwing injunction to “get a job!” is mirrored by the leftwing demand for “more jobs!”

As well as documenting personal misery, this book is a portrait of a society that has forgotten what it is for. Our economies have become “vast engines for producing nonsense”. Utopian ideals have been abandoned on all sides, replaced by praise for “hardworking families”. The rightwing injunction to “get a job!” is mirrored by the leftwing demand for “more jobs!” Ethics today is in a curious state. There is no shortage of people telling us that Western civilization is facing a moral crisis, that the old foundation of Christianity has been removed but nothing has been put in its place. Christian writers such as Alister McGrath and Nick Spencer have warned that we’re running on the moral capital of a religion we’ve long abandoned. It’s only a matter of time before, like Wile E. Coyote, we realize we’ve run off a moral cliff, impossibly suspended in mid-air only as long as we fail to realize there’s nothing under our feet.

Ethics today is in a curious state. There is no shortage of people telling us that Western civilization is facing a moral crisis, that the old foundation of Christianity has been removed but nothing has been put in its place. Christian writers such as Alister McGrath and Nick Spencer have warned that we’re running on the moral capital of a religion we’ve long abandoned. It’s only a matter of time before, like Wile E. Coyote, we realize we’ve run off a moral cliff, impossibly suspended in mid-air only as long as we fail to realize there’s nothing under our feet. It was bound to happen eventually. A group of researchers that may actually be competent and well-funded is investigating

It was bound to happen eventually. A group of researchers that may actually be competent and well-funded is investigating  I was at an academic conference last week, somewhere in America, where we were invited by our hosts to place a ‘preferred pronoun’ sticker on our nametags. “If you could pick one of those up during the next break, we’d appreciate it.” The options were, ‘He’, ‘She’, ‘They’, ‘Ask Me’, and one with a blank space for a write-in. Coming from my adoptive France, I had heard of this new practice in my country of origin, but somehow I had convinced myself that it was mostly mythical. Yet there were the stickers, and there were all my fellow participants, wearing them with straight faces.

I was at an academic conference last week, somewhere in America, where we were invited by our hosts to place a ‘preferred pronoun’ sticker on our nametags. “If you could pick one of those up during the next break, we’d appreciate it.” The options were, ‘He’, ‘She’, ‘They’, ‘Ask Me’, and one with a blank space for a write-in. Coming from my adoptive France, I had heard of this new practice in my country of origin, but somehow I had convinced myself that it was mostly mythical. Yet there were the stickers, and there were all my fellow participants, wearing them with straight faces.