by Emrys Westacott

On July 5 The Nation published a 14 line poem by Anders Carlson-Wee entitled “How-To.” The speaker in the poem is giving advice on how to beg. The poem begins:

On July 5 The Nation published a 14 line poem by Anders Carlson-Wee entitled “How-To.” The speaker in the poem is giving advice on how to beg. The poem begins:

If you got hiv, say aids. If you a girl,

say you’re pregnant–nobody gonna lower

themselves to listen for the kick.

The speaker exhibits a fairly sophisticated understanding of how the sensibilities of potential givers can be manipulated:

If you’re crippled don’t

flaunt it. Let ‘em think they’re good enough

Christians to notice.

The outlook of the speaker can reasonably be described as cynical, both regarding acceptable strategies to use when begging, and regarding the motives of the people targeted, who are taken to be moved not so much by compassion as by a desire to uphold a certain self-image. The poem concludes:

Don’t say you pray,

say you sin. It’s about who they believe

they is. You hardly even there.

The poem provoked fierce criticism on social media. People objected to Carlson-Wee using black vernacular speech patterns, to his making the speaker black, and to his inclusion of the word “crippled,” which some viewed as “ableist. The criticism prompted the editors at The Nation to issue an apology in which they wrote:

We are sorry for the pain we have caused to many communities affected by this poem….When we read the poem we took it as a profane, over-the-top attack on the ways in which members of many groups are asked, or required, to perform the work of marginalization. We can no longer read it that way.

Anders Carlson-Wee also offered an apology on Twitter, writing:

I am sorry for the pain I have caused, and I take responsibility for that. I intended the poem to address the invisibility of homelessness, and clearly it doesn’t work. Treading anywhere close to blackface is horrifying to me and I am profoundly regretful.

One of the downsides to social media is that controversies can easily reduce to a few verbal missiles–brief assertions, sharp put-downs, expressions of incredulity or outrage–tossed back and forth. For example, essayist Roxanne Gay, condemning Carlson-Wee (who is white) for using black vernacular locutions, offered all writers this advice: “Know your lane.” Katha Pollitt, who writes regularly for the nation, opined that the magazine’s apology “looks like a letter from a re-education camp.” What is needed, though, is a more careful reflection on the theoretical issues involved. Read more »

An equally pressing issue, which the US forces, especially, have yet to address, concerns the source, or sources, of all the Taliban’s new equipment. Providing logistics, massing fighters, and coordinating serial attacks around the country are the task of a well-drilled, well-supplied command structure. That is what Washington and Kabul are dealing with: a Taliban force, once considered a rag-tag army of militants, that now has the savvy of generals and the resources of a serious army.

An equally pressing issue, which the US forces, especially, have yet to address, concerns the source, or sources, of all the Taliban’s new equipment. Providing logistics, massing fighters, and coordinating serial attacks around the country are the task of a well-drilled, well-supplied command structure. That is what Washington and Kabul are dealing with: a Taliban force, once considered a rag-tag army of militants, that now has the savvy of generals and the resources of a serious army.

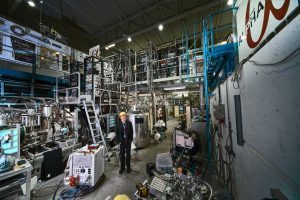

Replication is essential for building confidence in research studies

Replication is essential for building confidence in research studies

The main job of ‘culture’ in a modern society seems to be shielding people from the demands of morality. In its intellectual role it justifies inequality between citizens. In its national history role it gives citizens a delusional sense of their country’s significance and entitlement, followed by a dangerous sense of grievance when this isn’t sufficiently recognised by the rest of the world. In its identitarian role it deflects demands for justification into mere proclamations of fact: ‘Why do we do this or that awful thing?… Because shut up. It is who we are.’

The main job of ‘culture’ in a modern society seems to be shielding people from the demands of morality. In its intellectual role it justifies inequality between citizens. In its national history role it gives citizens a delusional sense of their country’s significance and entitlement, followed by a dangerous sense of grievance when this isn’t sufficiently recognised by the rest of the world. In its identitarian role it deflects demands for justification into mere proclamations of fact: ‘Why do we do this or that awful thing?… Because shut up. It is who we are.’

On July 5 The Nation published a 14 line poem by Anders Carlson-Wee entitled “

On July 5 The Nation published a 14 line poem by Anders Carlson-Wee entitled “ sickness was constantly diagnosed for the once powerful idea. And still, after the impressive Sanders campaign of 2016, the electoral success of Jeremy Corbyn in the 2017 general election, as well as the – for many – surprising victory of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in the democratic primary in New York, writers continue to assure us that the idea is, if not dead, having serious problems. In any case, the idea of socialism seemed until recently a relic of the industrial past with little to say about contemporary society.

sickness was constantly diagnosed for the once powerful idea. And still, after the impressive Sanders campaign of 2016, the electoral success of Jeremy Corbyn in the 2017 general election, as well as the – for many – surprising victory of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in the democratic primary in New York, writers continue to assure us that the idea is, if not dead, having serious problems. In any case, the idea of socialism seemed until recently a relic of the industrial past with little to say about contemporary society. First came the books describing just how much worse economic inequality had become over the past 20 years, with all the dramatic political implications now impossible to ignore. Then there were the tomes about globalization (including my own, I admit), detailing the West’s unfettered pursuit of neoliberal policies that abetted all this unfairness.

First came the books describing just how much worse economic inequality had become over the past 20 years, with all the dramatic political implications now impossible to ignore. Then there were the tomes about globalization (including my own, I admit), detailing the West’s unfettered pursuit of neoliberal policies that abetted all this unfairness. In a paper published today in the journal

In a paper published today in the journal  When I got to Walter Benjamin Platz, I figured I was in the wrong place. It wasn’t that I was lost, or had failed to follow the map correctly—it was that the place was wrong.

When I got to Walter Benjamin Platz, I figured I was in the wrong place. It wasn’t that I was lost, or had failed to follow the map correctly—it was that the place was wrong. It is Friday afternoon and a lively and diverse crowd starts to gather under a blazing August sun on the banks of the Tigris River, just metres away from al-Mutanabi Street, the Iraqi capital’s historic bookselling centre.

It is Friday afternoon and a lively and diverse crowd starts to gather under a blazing August sun on the banks of the Tigris River, just metres away from al-Mutanabi Street, the Iraqi capital’s historic bookselling centre. One day in March 2010, Isak McCune started clearing his throat with a forceful, violent sound. The New Hampshire toddler was 3, with a Beatles mop of blonde hair and a cuddly, loving personality. His parents had no idea where the guttural tic came from. They figured it was springtime allergies. Soon after, Isak began to scream as if in pain and grunt at his parents and peers. When he wasn’t throwing hours-long tantrums, he stared vacantly into space. By the time he was 5, he was plagued by insistent, terrifying thoughts of death. “He would smash his head into windows and glass whenever the word ‘dead’ came into his head. He was trying to drown out the thoughts,” says his mother, Robin McCune, a baker in Goffstown, a small town outside Manchester, New Hampshire’s largest city. Isak’s parents took him to pediatricians, therapy appointments, and psychiatrists. He was diagnosed with a host of disorders: sensory processing disorder, oppositional defiance disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). At 5, he spent a year on Prozac, “and seemed to get worse on it,” says Robin McCune. The McCunes tried to make peace with the idea that their son might never come back. In kindergarten, he grunted and screamed, frightening his teachers and classmates. “He started hearing voices, thought he saw things, he couldn’t go to the bathroom alone,” Robin McCune says. “His fear was immense and paralyzing.”

One day in March 2010, Isak McCune started clearing his throat with a forceful, violent sound. The New Hampshire toddler was 3, with a Beatles mop of blonde hair and a cuddly, loving personality. His parents had no idea where the guttural tic came from. They figured it was springtime allergies. Soon after, Isak began to scream as if in pain and grunt at his parents and peers. When he wasn’t throwing hours-long tantrums, he stared vacantly into space. By the time he was 5, he was plagued by insistent, terrifying thoughts of death. “He would smash his head into windows and glass whenever the word ‘dead’ came into his head. He was trying to drown out the thoughts,” says his mother, Robin McCune, a baker in Goffstown, a small town outside Manchester, New Hampshire’s largest city. Isak’s parents took him to pediatricians, therapy appointments, and psychiatrists. He was diagnosed with a host of disorders: sensory processing disorder, oppositional defiance disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). At 5, he spent a year on Prozac, “and seemed to get worse on it,” says Robin McCune. The McCunes tried to make peace with the idea that their son might never come back. In kindergarten, he grunted and screamed, frightening his teachers and classmates. “He started hearing voices, thought he saw things, he couldn’t go to the bathroom alone,” Robin McCune says. “His fear was immense and paralyzing.” In

In  Is capitalism immoral? Bill Gates, the second-richest man in the world, doesn’t believe that it has to be. In a recent interview, Gates argued that anyone with money has an ethical responsibility to do something positive with it. “Once you’ve taken care of yourself and your children, the best use of extra wealth is to give it back to society.” Gates himself lives this approach, recently giving away $4.6 billion in Microsoft shares to his philanthropic organization, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. “We are impatient optimists,” its webpage declares, “working to reduce inequity.”

Is capitalism immoral? Bill Gates, the second-richest man in the world, doesn’t believe that it has to be. In a recent interview, Gates argued that anyone with money has an ethical responsibility to do something positive with it. “Once you’ve taken care of yourself and your children, the best use of extra wealth is to give it back to society.” Gates himself lives this approach, recently giving away $4.6 billion in Microsoft shares to his philanthropic organization, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. “We are impatient optimists,” its webpage declares, “working to reduce inequity.” The awful news that all but two penguin chicks have starved to death out of a

The awful news that all but two penguin chicks have starved to death out of a