Samuel Moyn reviews A Foreign Policy for the Left by Michael Walzer in Modern Age:

Samuel Moyn reviews A Foreign Policy for the Left by Michael Walzer in Modern Age:

In A Foreign Policy for the Left, Walzer has updated some of the accessible and sprightly essays he published in Dissent and elsewhere since 2001 to explain how American progressives should think about their state’s global activities. His central argument is negative: the American left should not stick to what Walzer calls its “default” position of recommending standoffish withdrawal from world affairs.

Like an annoyed teacher who has seen generations of students repeat the same mistakes, Walzer lectures the left on the defects of the confection of anti-imperialism, isolationism, and pacifism he thinks it offers too reflexively. To the contrary, Walzer’s main point is that sometimes American hegemony, “internationalism,” and military force serve progressive ends.

I grant that it is sometimes genuinely worrisome when Americans, on both the left and the right, find excuses for disclaiming responsibility and doing nothing in response to international aggression or humanitarian abuses. But this fact hardly minimizes the even greater risk that Walzer courts—that of prettifying interventionism—as if it were the sole alternative to withdrawal. If inaction and isolation are sometimes sins, it is also true that America’s left and right have erred even more grossly through staunch interventionism and showy moralism.

Like many who defined their leftism around the cause of humanitarian intervention after the Cold War, Walzer is fixated on the quandary of when American military power should be deployed to prevent or halt mass atrocity. The experiences of the 1990s, from failures in the face of slaughter in Bosnia and Rwanda to “success” in Kosovo, crystallized a sense of obligation and even optimism about the beneficence of American force, if properly applied.

Unfortunately, the history of the current century points the other way: from Iraq (where many progressive hawks supported a catastrophic neoconservative adventure) to Trump’s recent Syrian intervention, the litany of armed American incursions has ranged from the feckless to the ruinous.

More here.

In the Municipal building on Livingston Street, two floors are reserved for Housing cases. In each court, dozens of people work and wait, a Bosch tableau with an international cast. HPD lawyers work the perimeter. They bring Respondents to the bench, confer with them in the hallway and negotiate with Petitioners on their behalf. HPD attorneys also lunch with landlord’s counsel. There is little ethical or proximate difference between Officers of the Court, save who signs their checks and the pay scales. To a person, they distribute a crushing weight, balancing malfeasance and negligence, plunder and systemic rot. The lasting effect of a day in Housing court isn’t the stipulation Management makes for repairs, nor the tenant’s payment (sometimes, less an abatement), it is feeling that force haul you down and watching others already borne off by it.

In the Municipal building on Livingston Street, two floors are reserved for Housing cases. In each court, dozens of people work and wait, a Bosch tableau with an international cast. HPD lawyers work the perimeter. They bring Respondents to the bench, confer with them in the hallway and negotiate with Petitioners on their behalf. HPD attorneys also lunch with landlord’s counsel. There is little ethical or proximate difference between Officers of the Court, save who signs their checks and the pay scales. To a person, they distribute a crushing weight, balancing malfeasance and negligence, plunder and systemic rot. The lasting effect of a day in Housing court isn’t the stipulation Management makes for repairs, nor the tenant’s payment (sometimes, less an abatement), it is feeling that force haul you down and watching others already borne off by it. Despite Dennett’s training in philosophy (at Oxford, no less, under Ryle), his appointment in a well-regarded philosophy department, and his continued self-identification as a philosopher (“Philosophers, like me” (407)), I suspect that many professional philosophers find Dennett’s From Bacteria to Bach and Back, if they read it all with any care, barely philosophy. Dennett offers few structured arguments (with carefully numbered premises), no clear dilemmas/trillemas (etc.) nor the apparent paradoxes that are the staple of our profession nor does he deploy the conceptual distinctions

Despite Dennett’s training in philosophy (at Oxford, no less, under Ryle), his appointment in a well-regarded philosophy department, and his continued self-identification as a philosopher (“Philosophers, like me” (407)), I suspect that many professional philosophers find Dennett’s From Bacteria to Bach and Back, if they read it all with any care, barely philosophy. Dennett offers few structured arguments (with carefully numbered premises), no clear dilemmas/trillemas (etc.) nor the apparent paradoxes that are the staple of our profession nor does he deploy the conceptual distinctions  Placards are being prepared. Photo-opportunities are being organised. A list of demands is being

Placards are being prepared. Photo-opportunities are being organised. A list of demands is being  Samuel Moyn reviews A Foreign Policy for the Left by Michael Walzer in Modern Age:

Samuel Moyn reviews A Foreign Policy for the Left by Michael Walzer in Modern Age: Before he died, Senator John McCain wrote a loving

Before he died, Senator John McCain wrote a loving  Sometimes I think my work may be seen eventually as some literary equivalent (obviously much reduced in scale) to Picasso. My vice, my strength, is beginnings. Usually I begin well—it is just that I seem to have little interest in finishing. It seems adequate to start a piece, go far enough to glimpse what the possibilities and limitations might be, and then move on. Which for that matter is close to the discrete temper of our time.

Sometimes I think my work may be seen eventually as some literary equivalent (obviously much reduced in scale) to Picasso. My vice, my strength, is beginnings. Usually I begin well—it is just that I seem to have little interest in finishing. It seems adequate to start a piece, go far enough to glimpse what the possibilities and limitations might be, and then move on. Which for that matter is close to the discrete temper of our time. John Horgan in Scientific American:

John Horgan in Scientific American: Chris Mackin in TNR:

Chris Mackin in TNR: But rationalism doesn’t make the magical universe go away. Possibly because I earn my living as a writer of fiction, and possibly because it’s just the sensible thing to do, I like to pay attention to everything I come across, including things that evoke the uncanny or the mysterious. Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto (I am human, I consider nothing human alien to me). My attitude to magical things is very much like that attributed to the great physicist Niels Bohr. Asked about the horseshoe that used to hang over the door to his laboratory, he’s claimed to have said that he didn’t believe it worked but he’d been told that it worked whether he believed in it or not. When it comes to belief in lucky charms, or rings engraved with the names of angels, or talismans with magic squares, it’s impossible to defend it and absurd to attack it on rational grounds because it’s not the kind of material on which reason operates. Reason is the wrong tool. Trying to understand superstition rationally is like trying to pick up something made of wood by using a magnet.

But rationalism doesn’t make the magical universe go away. Possibly because I earn my living as a writer of fiction, and possibly because it’s just the sensible thing to do, I like to pay attention to everything I come across, including things that evoke the uncanny or the mysterious. Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto (I am human, I consider nothing human alien to me). My attitude to magical things is very much like that attributed to the great physicist Niels Bohr. Asked about the horseshoe that used to hang over the door to his laboratory, he’s claimed to have said that he didn’t believe it worked but he’d been told that it worked whether he believed in it or not. When it comes to belief in lucky charms, or rings engraved with the names of angels, or talismans with magic squares, it’s impossible to defend it and absurd to attack it on rational grounds because it’s not the kind of material on which reason operates. Reason is the wrong tool. Trying to understand superstition rationally is like trying to pick up something made of wood by using a magnet. Perhaps it is Starnone’s newness in the English-speaking world that explains why reviewers have tended to jump over his proven track record and speculate about his connections to the mysterious and pseudonymous Italian author Elena Ferrante. Their rumored personal relationship is beside the point, but their books are similarly staggering—and the resemblances between their styles and subjects is hard to ignore.

Perhaps it is Starnone’s newness in the English-speaking world that explains why reviewers have tended to jump over his proven track record and speculate about his connections to the mysterious and pseudonymous Italian author Elena Ferrante. Their rumored personal relationship is beside the point, but their books are similarly staggering—and the resemblances between their styles and subjects is hard to ignore. The incredible temple of pity and terror, mirth and amazement, which is popularly known as Coney Island, really constitutes a perfectly unprecedented fusion of the circus and the theatre. It resembles the theatre, in that it fosters every known species of illusion. It suggests the circus, in that it puts us in touch with whatever is hair-raising, breath-taking and pore-opening. But Coney has a distinct drop on both theatre and circus. Whereas at the theatre we merely are deceived, at Coney we deceive ourselves. Whereas at the circus we are merely spectators of the impossible, at Coney we ourselves perform impossible feats—we turn all the heavenly somersaults imaginable and dare all the delirious dangers conceivable; and when, rushing at horrid velocity over irrevocable precipices, we beard the force of gravity in his lair, no acrobat, no lion tamer, can compete with us.

The incredible temple of pity and terror, mirth and amazement, which is popularly known as Coney Island, really constitutes a perfectly unprecedented fusion of the circus and the theatre. It resembles the theatre, in that it fosters every known species of illusion. It suggests the circus, in that it puts us in touch with whatever is hair-raising, breath-taking and pore-opening. But Coney has a distinct drop on both theatre and circus. Whereas at the theatre we merely are deceived, at Coney we deceive ourselves. Whereas at the circus we are merely spectators of the impossible, at Coney we ourselves perform impossible feats—we turn all the heavenly somersaults imaginable and dare all the delirious dangers conceivable; and when, rushing at horrid velocity over irrevocable precipices, we beard the force of gravity in his lair, no acrobat, no lion tamer, can compete with us. After World War II, tiny Albania became a hermit state, rigidly controlled by a Stalinist dictator,

After World War II, tiny Albania became a hermit state, rigidly controlled by a Stalinist dictator,  In April 2015, after a long and very public career, first as a male decathlete, then as a reality TV star,

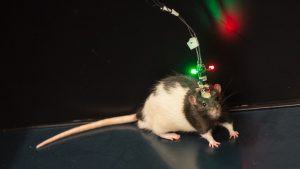

In April 2015, after a long and very public career, first as a male decathlete, then as a reality TV star,  How the brain fixes the timing of the events we experience depends on episodic memory. Whenever you remember key events from your past, you are tapping into episodic memory, which encodes what happened, where it happened, and when it happened, doing so for all our remembered experiences. Neuroscientists know the brain must have a kind of internal clock or pacemaker to help it track those experiences and record them as memories.

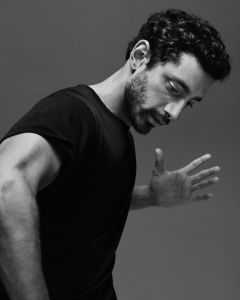

How the brain fixes the timing of the events we experience depends on episodic memory. Whenever you remember key events from your past, you are tapping into episodic memory, which encodes what happened, where it happened, and when it happened, doing so for all our remembered experiences. Neuroscientists know the brain must have a kind of internal clock or pacemaker to help it track those experiences and record them as memories. When I let it slip that the press kit I’d been given had referred to him as a ‘Renaissance man,’ Riz Ahmed looked angrily down into his breakfast, a chicken-quinoa bowl with extra chicken. It lasted for just a moment, but the image stayed with me, because it was the only time during our approximately 10 hours together — breakfast in Brooklyn, private sessions with the Islamic art collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, YouTube sessions listening to 1970s Qawwali-inspired Iraqi disco, talks on park benches in Fort Greene, tea on the sidewalk of Fulton Avenue and even dinner in Boston, where Ahmed was filming an independent feature about a heavy-metal drummer who’s losing his hearing — that the 35-year-old actor seemed to be truly, genuinely upset.

When I let it slip that the press kit I’d been given had referred to him as a ‘Renaissance man,’ Riz Ahmed looked angrily down into his breakfast, a chicken-quinoa bowl with extra chicken. It lasted for just a moment, but the image stayed with me, because it was the only time during our approximately 10 hours together — breakfast in Brooklyn, private sessions with the Islamic art collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, YouTube sessions listening to 1970s Qawwali-inspired Iraqi disco, talks on park benches in Fort Greene, tea on the sidewalk of Fulton Avenue and even dinner in Boston, where Ahmed was filming an independent feature about a heavy-metal drummer who’s losing his hearing — that the 35-year-old actor seemed to be truly, genuinely upset.