Jonathan Shaw in Harvard Magazine:

The pyramids and the Great Sphinx rise inexplicably from the desert at Giza, relics of a vanished culture. They dwarf the approaching sprawl of modern Cairo, a city of 16 million. The largest pyramid, built for the Pharaoh Khufu around 2530 B.C. and intended to last an eternity, was until early in the twentieth century the biggest building on the planet. To raise it, laborers moved into position six and a half million tons of stone—some in blocks as large as nine tons—with nothing but wood and rope. During the last 4,500 years, the pyramids have drawn every kind of admiration and interest, ranging in ancient times from religious worship to grave robbery, and, in the modern era, from New-Age claims for healing “pyramid power” to pseudoscientific searches by “fantastic archaeologists” seeking hidden chambers or signs of alien visitations to Earth. As feats of engineering or testaments to the decades-long labor of tens of thousands, they have awed even the most sober observers.

The pyramids and the Great Sphinx rise inexplicably from the desert at Giza, relics of a vanished culture. They dwarf the approaching sprawl of modern Cairo, a city of 16 million. The largest pyramid, built for the Pharaoh Khufu around 2530 B.C. and intended to last an eternity, was until early in the twentieth century the biggest building on the planet. To raise it, laborers moved into position six and a half million tons of stone—some in blocks as large as nine tons—with nothing but wood and rope. During the last 4,500 years, the pyramids have drawn every kind of admiration and interest, ranging in ancient times from religious worship to grave robbery, and, in the modern era, from New-Age claims for healing “pyramid power” to pseudoscientific searches by “fantastic archaeologists” seeking hidden chambers or signs of alien visitations to Earth. As feats of engineering or testaments to the decades-long labor of tens of thousands, they have awed even the most sober observers.

The question of who labored to build them, and why, has long been part of their fascination. Rooted firmly in the popular imagination is the idea that the pyramids were built by slaves serving a merciless pharaoh. This notion of a vast slave class in Egypt originated in Judeo-Christian tradition and has been popularized by Hollywood productions like Cecil B. De Mille’s The Ten Commandments, in which a captive people labor in the scorching sun beneath the whips of pharaoh’s overseers. But graffiti from inside the Giza monuments themselves have long suggested something very different.

More here.

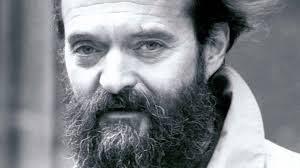

Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) is one of those fortunate composers who has created his own world in music—and is beloved for it in his lifetime. The Estonian, who for the last decade has been the world’s most performed living composer, started his career writing neoclassical pieces influenced by the Russian greats, chiefly Prokofiev and Shostakovich. Then he discovered Schoenberg’s twelve-tone scale, serialism, and other twentieth-century experimental techniques and soon became a prominent member of the avant-garde. But Soviet censors disapproved, and in the late 1960s their unofficial censorship removed Pärt’s music from concert programs and sent him into what he called a “period of contemplative silence.”

Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) is one of those fortunate composers who has created his own world in music—and is beloved for it in his lifetime. The Estonian, who for the last decade has been the world’s most performed living composer, started his career writing neoclassical pieces influenced by the Russian greats, chiefly Prokofiev and Shostakovich. Then he discovered Schoenberg’s twelve-tone scale, serialism, and other twentieth-century experimental techniques and soon became a prominent member of the avant-garde. But Soviet censors disapproved, and in the late 1960s their unofficial censorship removed Pärt’s music from concert programs and sent him into what he called a “period of contemplative silence.” But it wasn’t as if, by leaving church, I could escape. In the Midwest, everything is haunted by Jesus: the Rust Belt towns, the long gray freeways; county fairs in the summer with headlining Christian bands; breweries full of wholesome Christian hipsters in warm sweaters, Iron and Wine or Sufjan Stevens on the sound system. After belief, I didn’t want to drive through the suburbs and come upon some postwar church with hymnals full of

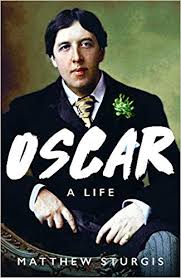

But it wasn’t as if, by leaving church, I could escape. In the Midwest, everything is haunted by Jesus: the Rust Belt towns, the long gray freeways; county fairs in the summer with headlining Christian bands; breweries full of wholesome Christian hipsters in warm sweaters, Iron and Wine or Sufjan Stevens on the sound system. After belief, I didn’t want to drive through the suburbs and come upon some postwar church with hymnals full of  Each critic sees him- or herself in Oscar Wilde. Saint Oscar; Wilde the Irishman; Wilde the wit. The classicist; the socialist; the martyr for gay rights. “To be premature is to be perfect”, Wilde wrote; “History lives through its anachronisms.” It is in large part on this quality that the Wilde industry has been built. For an industry it certainly is. Books on Wilde are glamorous in a way that academic monographs seldom are. They come with beautiful artwork and endorsements by Stephen Fry. They lend themselves to the crossover market, eminently desirable to publishers as monograph sales dwindle. At their zenith, they beget publicity tours and a spot on a Waterstones table. In a world where most of us academics regularly spend weeks preparing a conference paper to deliver before an audience of a dozen, this is stardom.

Each critic sees him- or herself in Oscar Wilde. Saint Oscar; Wilde the Irishman; Wilde the wit. The classicist; the socialist; the martyr for gay rights. “To be premature is to be perfect”, Wilde wrote; “History lives through its anachronisms.” It is in large part on this quality that the Wilde industry has been built. For an industry it certainly is. Books on Wilde are glamorous in a way that academic monographs seldom are. They come with beautiful artwork and endorsements by Stephen Fry. They lend themselves to the crossover market, eminently desirable to publishers as monograph sales dwindle. At their zenith, they beget publicity tours and a spot on a Waterstones table. In a world where most of us academics regularly spend weeks preparing a conference paper to deliver before an audience of a dozen, this is stardom.

Meena Alexander, a poet and scholar whose writings reflected the search for identity that came with a peripatetic life, including time in India, Africa, Europe and the United States, died on Wednesday in Manhattan. She was 67.

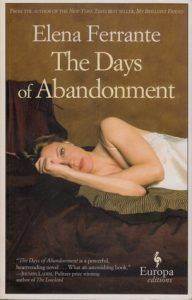

Meena Alexander, a poet and scholar whose writings reflected the search for identity that came with a peripatetic life, including time in India, Africa, Europe and the United States, died on Wednesday in Manhattan. She was 67. Blurbs, the quoted testimonials of a book’s virtues by other authors, are now so ubiquitous, readers expect them, first-time authors stress about getting them, booksellers base orders on them. A blank back cover today would probably look like a production mistake. But while readers heft books in their hands and scrutinize the praise, it should be noted that blurbs are not ad copy written by some copywriter; they are ad copy written by a fellow author. “Ad copy” might be a bit harsh, but maybe not. The “flap copy,” the wordage on the inside flap of the cover of a hard cover, is written by the publishers, to tell potential readers what the book is about but also, of course, to spur a purchase. Blurbs are also there for promotional purposes only, their bias similarly implicit. “Why is this even a book?” I saw in a book review for a tepid memoir that I read in galleys and enthusiastically thought the same thing about. But such an honest negative assessment is not going to make it as a blurb, nor does an author’s effusive praise guarantee that the book has been read. Random people I interviewed for this piece didn’t know what blurbs were—when I asked about their persuasiveness/necessity, most said they thought they were necessary, but then I realized they were referring to the “flap copy” on the inside cover. Most readers I spoke to casually, including my niece, a college student who can’t leave a bookstore without at least 50 pounds of books, seemed pretty agnostic-to-meh about blurbs and mostly ignored them while browsing.

Blurbs, the quoted testimonials of a book’s virtues by other authors, are now so ubiquitous, readers expect them, first-time authors stress about getting them, booksellers base orders on them. A blank back cover today would probably look like a production mistake. But while readers heft books in their hands and scrutinize the praise, it should be noted that blurbs are not ad copy written by some copywriter; they are ad copy written by a fellow author. “Ad copy” might be a bit harsh, but maybe not. The “flap copy,” the wordage on the inside flap of the cover of a hard cover, is written by the publishers, to tell potential readers what the book is about but also, of course, to spur a purchase. Blurbs are also there for promotional purposes only, their bias similarly implicit. “Why is this even a book?” I saw in a book review for a tepid memoir that I read in galleys and enthusiastically thought the same thing about. But such an honest negative assessment is not going to make it as a blurb, nor does an author’s effusive praise guarantee that the book has been read. Random people I interviewed for this piece didn’t know what blurbs were—when I asked about their persuasiveness/necessity, most said they thought they were necessary, but then I realized they were referring to the “flap copy” on the inside cover. Most readers I spoke to casually, including my niece, a college student who can’t leave a bookstore without at least 50 pounds of books, seemed pretty agnostic-to-meh about blurbs and mostly ignored them while browsing. Consistent with Mouffe’s other writings, For a Left Populism draws on the work of two interwar intellectuals: Carl Schmitt and Antonio Gramsci. It might seem strange to place the thought of “the crown jurist of the Third Reich” alongside that of a leader of the Italian Communist Party who was imprisoned by Mussolini’s government, but Mouffe finds in both figures conceptual resources for what she calls an anti-essentialist leftism. From Gramsci, Mouffe takes the concept of hegemony; from Schmitt, the concept of the political. Hegemony names the form of power that cannot be reduced to brute repression alone. Rather, a dominant social group attains hegemony when subaltern groups voluntarily submit to its rule, not under the barrel of a gun but through the force of “common sense” and affective attachments to the existing order. As a corollary, any counter-hegemonic movement from below must contest the prevailing order and the class interests it serves by engaging not only the state but also civil society. Churches, schools, trade unions, sports teams, and all manner of voluntary associations are the battlegrounds of hegemonic struggle.

Consistent with Mouffe’s other writings, For a Left Populism draws on the work of two interwar intellectuals: Carl Schmitt and Antonio Gramsci. It might seem strange to place the thought of “the crown jurist of the Third Reich” alongside that of a leader of the Italian Communist Party who was imprisoned by Mussolini’s government, but Mouffe finds in both figures conceptual resources for what she calls an anti-essentialist leftism. From Gramsci, Mouffe takes the concept of hegemony; from Schmitt, the concept of the political. Hegemony names the form of power that cannot be reduced to brute repression alone. Rather, a dominant social group attains hegemony when subaltern groups voluntarily submit to its rule, not under the barrel of a gun but through the force of “common sense” and affective attachments to the existing order. As a corollary, any counter-hegemonic movement from below must contest the prevailing order and the class interests it serves by engaging not only the state but also civil society. Churches, schools, trade unions, sports teams, and all manner of voluntary associations are the battlegrounds of hegemonic struggle. In her 2002 novel

In her 2002 novel  There’s an unexpectedly amusing passage in the great German philosopher Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Judgment. Kant is deliberating upon lofty issues like how and why we consider something beautiful. In the course of his complicated philosophical maneuverings he pauses to mention, by way of example, a number of pleasing designs to be found in nature. And then, in a twist, he muses briefly on how the eye and mind delight in the incredible shapes and forms of… wallpaper. Yes, wallpaper.

There’s an unexpectedly amusing passage in the great German philosopher Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Judgment. Kant is deliberating upon lofty issues like how and why we consider something beautiful. In the course of his complicated philosophical maneuverings he pauses to mention, by way of example, a number of pleasing designs to be found in nature. And then, in a twist, he muses briefly on how the eye and mind delight in the incredible shapes and forms of… wallpaper. Yes, wallpaper. I remember vividly hosting a colloquium speaker, about fifteen years ago, who talked about the

I remember vividly hosting a colloquium speaker, about fifteen years ago, who talked about the  We are the editors of the Journal of Controversial Ideas, which was criticised by Nesrine Malik (

We are the editors of the Journal of Controversial Ideas, which was criticised by Nesrine Malik ( If a decline in quality writ large is indeed evident on the networks and streaming services, one could hardly guess it from the continuing tone of TV coverage. This summer, Sepinwall—recently ensconced at Rolling Stone, long Hollywood’s most reliable cheerleader outside of the trade rags—proclaimed The Americans “one of the great TV dramas of this era,” named Atlanta’s debut season “one of the best and boldest in recent memory,” and labeled Barry “the blackest of black comic stories.”

If a decline in quality writ large is indeed evident on the networks and streaming services, one could hardly guess it from the continuing tone of TV coverage. This summer, Sepinwall—recently ensconced at Rolling Stone, long Hollywood’s most reliable cheerleader outside of the trade rags—proclaimed The Americans “one of the great TV dramas of this era,” named Atlanta’s debut season “one of the best and boldest in recent memory,” and labeled Barry “the blackest of black comic stories.”