(Following Hurrican Katrina) Ethel Freeman’s body sat for days in her wheelchair

outside the New Orleans Convention Center. Her son Herbert, who had assured his

mother that help was on the way, was forced to leave her there once she died.

Ethel’s Sestina

Gon’ be obedient in this here chair,

gon’ bide my time, fanning against this sun.

I ask my boy, and all he says is Wait.

He wipes my brow with steam, says I should sleep.

I trust his every word. Herbert my son.

I believe him when he says help gon’ come.

Been so long since all these suffrin’ folks come

to this place. Now on the ground ’round my chair,

they sweat in my shade, keep asking my son

could that be a bus they see. It’s the sun

foolin’ them, shining much too loud for sleep,

making us hear engines, wheels. Not yet. Wait.

Lawd, some folks prayin’ for rain while they wait,

forgetting what rain can do. When it come,

it smashes living flat, wakes you from sleep,

eats streets, washes you clean out of the chair

you be sittin’ in. Best to praise this sun,

shinin’ its dry shine. Lawd have mercy, son,

is it coming? Such a strong man, my son.

Can’t help but believe when he tells us, Wait.

Wait some more. Wish some trees would block this sun.

We wait. Ain’t no white men or buses come,

but look—see that there? Get me out this chair,

help me stand on up. No time for sleepin’,

cause look what’s rumbling this way. If you sleep

you gon’ miss it. Look there, I tell my son.

He don’t hear. I’m ’bout to get out this chair,

but the ghost in my legs tells me to wait,

wait for the salvation that’s sho to come.

I see my savior’s face ’longside that sun.

Nobody sees me running toward the sun.

Lawd, they think I done gone and fell asleep.

They don’t hear Come.

Read more »

In the beginning, there was smoke. It snaked out of the Andes from the burning leaves of Nicotiana tabacum some 6,000 years ago, spreading across the lands that would come to be known as South America and the Caribbean, until finally reaching the eastern shores of North America. It intermingled with wisps from other plants: kinnickinnick and Datura and passionflower. At first, it meant ceremony. Later, it meant profit. But always the importance of the smoke remained.

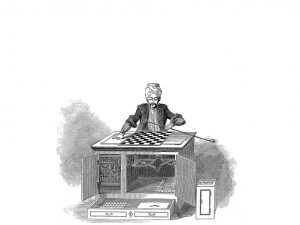

In the beginning, there was smoke. It snaked out of the Andes from the burning leaves of Nicotiana tabacum some 6,000 years ago, spreading across the lands that would come to be known as South America and the Caribbean, until finally reaching the eastern shores of North America. It intermingled with wisps from other plants: kinnickinnick and Datura and passionflower. At first, it meant ceremony. Later, it meant profit. But always the importance of the smoke remained. In 1770 a chess-playing robot, built by a Hungarian inventor, caused a sensation across Europe. It took the form of a life-size wooden figure, dressed in Turkish clothing, seated behind a cabinet which had a chessboard on top. Its clockwork arm could reach out and move pieces on the board. The Mechanical Turk was capable of beating even the best players at chess. Built to amuse the empress Maria Theresa, its fame spread far beyond Vienna, and visitors to her court insisted on seeing it. The Turk toured Europe in the 1780s, prompting much speculation about how it worked, and whether a machine could really think: the Industrial Revolution was just getting started, and many people were questioning to what extent machines could replace people. Nobody ever quite guessed the Turk’s secret. But it eventually transpired that there was a human chess player cleverly concealed in its innards. The apparently intelligent machine depended on a person hidden inside.

In 1770 a chess-playing robot, built by a Hungarian inventor, caused a sensation across Europe. It took the form of a life-size wooden figure, dressed in Turkish clothing, seated behind a cabinet which had a chessboard on top. Its clockwork arm could reach out and move pieces on the board. The Mechanical Turk was capable of beating even the best players at chess. Built to amuse the empress Maria Theresa, its fame spread far beyond Vienna, and visitors to her court insisted on seeing it. The Turk toured Europe in the 1780s, prompting much speculation about how it worked, and whether a machine could really think: the Industrial Revolution was just getting started, and many people were questioning to what extent machines could replace people. Nobody ever quite guessed the Turk’s secret. But it eventually transpired that there was a human chess player cleverly concealed in its innards. The apparently intelligent machine depended on a person hidden inside.

I can’t understand the words. Heck, I can’t even identify all the instruments these guys are playing, but I am loving The HU.

I can’t understand the words. Heck, I can’t even identify all the instruments these guys are playing, but I am loving The HU. Despite Christine Blasey Ford’s stirring testimony, an FBI investigation, thousands of protesters (hundreds of whom were arrested), petitions and phone calls from constituents, an

Despite Christine Blasey Ford’s stirring testimony, an FBI investigation, thousands of protesters (hundreds of whom were arrested), petitions and phone calls from constituents, an  Sune Boye Riis was on a bike ride with his youngest son, enjoying the sun slanting over the fields and woodlands near their home north of Copenhagen, when it suddenly occurred to him that something about the experience was amiss. Specifically, something was missing.

Sune Boye Riis was on a bike ride with his youngest son, enjoying the sun slanting over the fields and woodlands near their home north of Copenhagen, when it suddenly occurred to him that something about the experience was amiss. Specifically, something was missing. The last forty years have seen a transformation in American business. Three major airlines dominate the skies. About ten pharmaceutical companies make up the lion’s share of the industry. Three major companies constitute the seed and pesticide industry. And 70 percent of beer is sold to one of two conglomerates. Scholars have shown that this wave of consolidation has depressed wages, increased inequality, and arrested small business formation. The decline in competition is so plain that even centrist organizations like The Economist and the Brookings Institution have

The last forty years have seen a transformation in American business. Three major airlines dominate the skies. About ten pharmaceutical companies make up the lion’s share of the industry. Three major companies constitute the seed and pesticide industry. And 70 percent of beer is sold to one of two conglomerates. Scholars have shown that this wave of consolidation has depressed wages, increased inequality, and arrested small business formation. The decline in competition is so plain that even centrist organizations like The Economist and the Brookings Institution have  Much has been written about the courageous rebuilding of the Iraqi libraries destroyed by the Islamic State during its occupation of Mosul and other cities in the region. In adjacent Kurdish Iraq, the centuries-old struggle to build a repository of Kurdish culture and history has primarily and often necessarily continued with little visibility or fanfare, undertaken by willful idealists and brave individualists. Recently, I visited Zheen Archive Center, and met the people making that dream a reality. Here, two optimistic, broadminded brothers and an all-women team of crack manuscript preservationists are building a collection of books, manuscripts, and papers that have survived hundreds of years of language bans and the mass destruction of property that accompanied the countless murders of Saddam Hussein’s 1980s genocidal campaign, Anfal. Zheen—which means “life” in the Sorani dialect of Kurdish—houses the greatest collection of Kurdish cultural material of any other institution in the four contemporary nation-states that comprise the region of the Kurds, and probably the world. Remarkably, the Salih brothers formally founded Zheen in just 2004, and only acquired their present location, the nondescript four-story office building that houses its archives in northwest Sulaimani, in 2009.

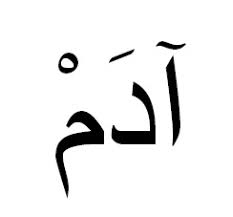

Much has been written about the courageous rebuilding of the Iraqi libraries destroyed by the Islamic State during its occupation of Mosul and other cities in the region. In adjacent Kurdish Iraq, the centuries-old struggle to build a repository of Kurdish culture and history has primarily and often necessarily continued with little visibility or fanfare, undertaken by willful idealists and brave individualists. Recently, I visited Zheen Archive Center, and met the people making that dream a reality. Here, two optimistic, broadminded brothers and an all-women team of crack manuscript preservationists are building a collection of books, manuscripts, and papers that have survived hundreds of years of language bans and the mass destruction of property that accompanied the countless murders of Saddam Hussein’s 1980s genocidal campaign, Anfal. Zheen—which means “life” in the Sorani dialect of Kurdish—houses the greatest collection of Kurdish cultural material of any other institution in the four contemporary nation-states that comprise the region of the Kurds, and probably the world. Remarkably, the Salih brothers formally founded Zheen in just 2004, and only acquired their present location, the nondescript four-story office building that houses its archives in northwest Sulaimani, in 2009. No story captures the lonely act of naming as a truly human capacity better than Daniel Defoe’s novel Robinson Crusoe (1719), where it saves the shipwrecked Crusoe from disintegration. Here, the logic of naming acquires a new twist. Friday—not an animal, but an aboriginal from a nearby island—becomes the center of his universe, the saving grace of his dwindling powers of perception, the focal point in his attempts to restructure something that at least looks like a society. Friday is not particularly responsive. But Crusoe invents a whole new kind of mastery, one in which Friday, in fact, becomes wholly redundant. Crusoe does not need Friday to confirm his powers. He does not need such affirmation because he has invented the technology of naming. Friday is named after a day in the calendar, and not according to a higher principle. He is named according to a certain principle of contingency, an operation of chance that can be repeated, serially, in as many varieties and forms as one likes. The question is no longer if names come from God or not, but rather how we are to produce them in the most efficient manner possible.

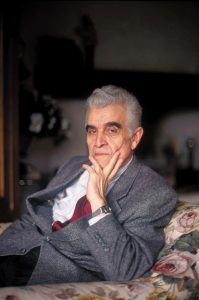

No story captures the lonely act of naming as a truly human capacity better than Daniel Defoe’s novel Robinson Crusoe (1719), where it saves the shipwrecked Crusoe from disintegration. Here, the logic of naming acquires a new twist. Friday—not an animal, but an aboriginal from a nearby island—becomes the center of his universe, the saving grace of his dwindling powers of perception, the focal point in his attempts to restructure something that at least looks like a society. Friday is not particularly responsive. But Crusoe invents a whole new kind of mastery, one in which Friday, in fact, becomes wholly redundant. Crusoe does not need Friday to confirm his powers. He does not need such affirmation because he has invented the technology of naming. Friday is named after a day in the calendar, and not according to a higher principle. He is named according to a certain principle of contingency, an operation of chance that can be repeated, serially, in as many varieties and forms as one likes. The question is no longer if names come from God or not, but rather how we are to produce them in the most efficient manner possible. Is this a good moment – propitious, welcoming – for the appearance of a long, rich and unflaggingly detailed account of the later life of Saul Bellow? Ten years in the making, Zachary Leader’s biography was rubber-stamped at an earlier and distinctively different point in time. Then, the writer still reflected the glow of adulation – from the reviews of James Atlas’s single-volume biography Bellow(2000); his final novel Ravelstein (2000) and his Collected Stories (2001); from the 50th-anniversary tributes to The Adventures of Augie March in 2003 and the appearance, the same year, of the Library of America compendium, Novels 1944-1953; and from the obituaries and memorial essays that appeared on his death in 2005, aged 89. When, around that time, I starting getting interested in fiction, I was made to feel about Bellow’s writing more or less what Charlie Citrine, in Humboldt’s Gift (1975), recalls feeling about Leon Trotsky in the 1930s – that if I didn’t read him at once, I wouldn’t be worth conversing with.

Is this a good moment – propitious, welcoming – for the appearance of a long, rich and unflaggingly detailed account of the later life of Saul Bellow? Ten years in the making, Zachary Leader’s biography was rubber-stamped at an earlier and distinctively different point in time. Then, the writer still reflected the glow of adulation – from the reviews of James Atlas’s single-volume biography Bellow(2000); his final novel Ravelstein (2000) and his Collected Stories (2001); from the 50th-anniversary tributes to The Adventures of Augie March in 2003 and the appearance, the same year, of the Library of America compendium, Novels 1944-1953; and from the obituaries and memorial essays that appeared on his death in 2005, aged 89. When, around that time, I starting getting interested in fiction, I was made to feel about Bellow’s writing more or less what Charlie Citrine, in Humboldt’s Gift (1975), recalls feeling about Leon Trotsky in the 1930s – that if I didn’t read him at once, I wouldn’t be worth conversing with. “I was a human first, and then I learned to be a

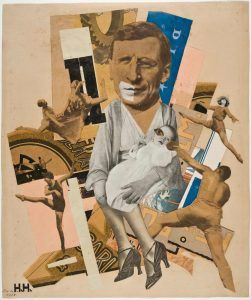

“I was a human first, and then I learned to be a  In 1919 the German Dada artist Raoul Hausmann dismissed marriage as “the projection of rape into law”. It’s a statement that relishes its own violence: he is limbering up to fight marriage to the death. A strange mixture of dandy, wild man, provocateur and social engineer, Hausmann believed that the socialist revolution the Dadaists sought couldn’t be attained without a corresponding sexual revolution. And he lived as he preached. He was married, but was also in a four-year relationship with fellow artist

In 1919 the German Dada artist Raoul Hausmann dismissed marriage as “the projection of rape into law”. It’s a statement that relishes its own violence: he is limbering up to fight marriage to the death. A strange mixture of dandy, wild man, provocateur and social engineer, Hausmann believed that the socialist revolution the Dadaists sought couldn’t be attained without a corresponding sexual revolution. And he lived as he preached. He was married, but was also in a four-year relationship with fellow artist  Last November, on the Monday before Thanksgiving, David* was sitting in traffic on his drive home from work. He was suddenly overwhelmed by the realization that everything he experienced was filtered through his brain, entirely subjective, and possibly a complete fabrication.

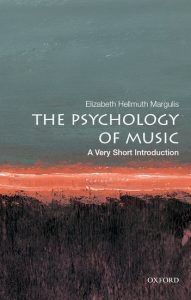

Last November, on the Monday before Thanksgiving, David* was sitting in traffic on his drive home from work. He was suddenly overwhelmed by the realization that everything he experienced was filtered through his brain, entirely subjective, and possibly a complete fabrication. Music can intensify moments of elation and moments of despair. It can connect people and it can divide them. The prospect of psychologists turning their lens on music might give a person the heebie-jeebies, however, conjuring up an image of humorless people in white lab coats manipulating sequences of beeps and boops to make grand pronouncements about human musicality.

Music can intensify moments of elation and moments of despair. It can connect people and it can divide them. The prospect of psychologists turning their lens on music might give a person the heebie-jeebies, however, conjuring up an image of humorless people in white lab coats manipulating sequences of beeps and boops to make grand pronouncements about human musicality. I was born in Hamburg, Germany, in 1949, so I grew up playing cowboys and Indians with my cousins in the rubble fields of my native city. Family lore had it that my mother, who had survived the Hamburg firestorm of 1943, made me baby shirts from the sugar bags that came in American care packages. Her father had been sent to a concentration camp during the early days of the Nazi dictatorship because he collected dues for an illegal union; fortunately, he survived. Because of the housing shortage caused by the bombings, my parents and I, for the first 11 years of my life, lived in a one-room apartment. Suffice it to say my childhood was a daily reminder of the catastrophic consequences of the destruction of the Weimar democracy and the rise of Adolf Hitler.

I was born in Hamburg, Germany, in 1949, so I grew up playing cowboys and Indians with my cousins in the rubble fields of my native city. Family lore had it that my mother, who had survived the Hamburg firestorm of 1943, made me baby shirts from the sugar bags that came in American care packages. Her father had been sent to a concentration camp during the early days of the Nazi dictatorship because he collected dues for an illegal union; fortunately, he survived. Because of the housing shortage caused by the bombings, my parents and I, for the first 11 years of my life, lived in a one-room apartment. Suffice it to say my childhood was a daily reminder of the catastrophic consequences of the destruction of the Weimar democracy and the rise of Adolf Hitler.