Jean-Luc Nancy in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

POPULISM AND DEMOCRACY are an odd couple. The first, populism, rejects the pejorative connotation that its name represents for the second, democracy, which it in turn criticizes for being hypocritical. The second declares itself the sole form of legitimate existence. Both of them claim to be supremely popular. Their virulent opposition in the current discourse is matched only by the indecision that hangs over their respective meanings. What “people” are they talking about, both together and separately?

POPULISM AND DEMOCRACY are an odd couple. The first, populism, rejects the pejorative connotation that its name represents for the second, democracy, which it in turn criticizes for being hypocritical. The second declares itself the sole form of legitimate existence. Both of them claim to be supremely popular. Their virulent opposition in the current discourse is matched only by the indecision that hangs over their respective meanings. What “people” are they talking about, both together and separately?

The Latin populus and the Greek demos, which, despite important differences, are sometimes translated one for the other, have one thing in common: both involve the assembly of those belonging to an organized collectivity as a public reality (res publica — this word is related to populus). Considered as a totality, the people is identical to the public thing, itself identified as city, nation, homeland, state, or, precisely, “Republic.” The word people functions, then, like a sort of tautology of belonging or affiliation. Considered from within the republic, the people is distinct both from instances of public authority (consider the famous formula senatus populusque romanus) and from the populist fringe whose membership always remains doubtful: the “masses,” or “plebes” (another word from the same family). Between internal distinctions and external identity, attractions and repulsions are constantly being played out.

In fact, to put it succinctly, identity is de jure: it is not simply given, but must be conceived and instituted, while distinctions are de facto: the so-called social contract does not function without the need for governance or without the pressures of refusal or opposition. Assenting to the public institution cannot happen without the dissent of the passions (whether they be those of interest, inclination, or impulse).

More here.

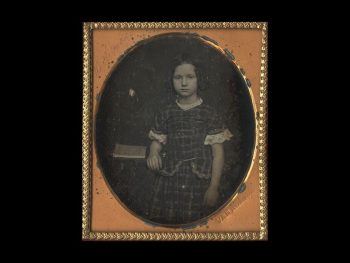

On February 19, 1855, Charles Sumner, the Massachusetts senator, wrote his supporters about an enslaved 7-year-old girl whose freedom he had helped to secure. She would be joining him onstage at an abolitionist lecture that spring. “I think her presence among us (in Boston) will be a great deal more effective than any speech I could make,” the noted orator wrote. He said her name was Mary, but he also referred to her, significantly, as “another Ida May.” Sumner enclosed a daguerreotype of Mary standing next to a small table with a notebook at her elbow. She is neatly outfitted in a plaid dress, with a solemn expression on her face, and looks for all the world like a white girl from a well-to-do family.

On February 19, 1855, Charles Sumner, the Massachusetts senator, wrote his supporters about an enslaved 7-year-old girl whose freedom he had helped to secure. She would be joining him onstage at an abolitionist lecture that spring. “I think her presence among us (in Boston) will be a great deal more effective than any speech I could make,” the noted orator wrote. He said her name was Mary, but he also referred to her, significantly, as “another Ida May.” Sumner enclosed a daguerreotype of Mary standing next to a small table with a notebook at her elbow. She is neatly outfitted in a plaid dress, with a solemn expression on her face, and looks for all the world like a white girl from a well-to-do family.

In 1985, the chemist Steven A. Benner sat down with some colleagues and a notebook and sketched out a way to expand the alphabet of DNA. He has been trying to make those sketches real ever since.

In 1985, the chemist Steven A. Benner sat down with some colleagues and a notebook and sketched out a way to expand the alphabet of DNA. He has been trying to make those sketches real ever since. One evening in 2016, a twenty-five-year-old community-college student named Alex Gutiérrez was waiting tables at La Piazza Ristorante Italiano, an upscale restaurant in Tulare, in California’s San Joaquin Valley. Gutiérrez spotted Yorai Benzeevi, a physician who ran the local hospital, sitting at a table with Parmod Kumar, a member of the hospital board. They seemed to be in a celebratory mood, drinking expensive bottles of wine and laughing. This irritated Gutiérrez. The kingpins, he thought with disgust.

One evening in 2016, a twenty-five-year-old community-college student named Alex Gutiérrez was waiting tables at La Piazza Ristorante Italiano, an upscale restaurant in Tulare, in California’s San Joaquin Valley. Gutiérrez spotted Yorai Benzeevi, a physician who ran the local hospital, sitting at a table with Parmod Kumar, a member of the hospital board. They seemed to be in a celebratory mood, drinking expensive bottles of wine and laughing. This irritated Gutiérrez. The kingpins, he thought with disgust. Lynn Nottage is the only living American playwright to have won the Pulitzer Prize multiple times. Her first one came in 2009 for Ruined, a drama about a small bar in a mining town in the Congo that serves soldiers from both sides of that country’s civil war. She received her second Pulitzer in 2017 for Sweat, a drama about the downfall of Reading, Pennsylvania, that largely takes place in a bar frequented by union workers as they find themselves caught between solidarity and trying to make rent.

Lynn Nottage is the only living American playwright to have won the Pulitzer Prize multiple times. Her first one came in 2009 for Ruined, a drama about a small bar in a mining town in the Congo that serves soldiers from both sides of that country’s civil war. She received her second Pulitzer in 2017 for Sweat, a drama about the downfall of Reading, Pennsylvania, that largely takes place in a bar frequented by union workers as they find themselves caught between solidarity and trying to make rent. The

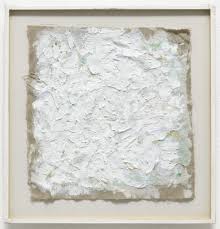

The Over the course of the more than half-century of relentless experimentation that followed, Ryman radically expanded the possibilities of abstract painting, continuously rethinking how it could be made and what it could look like, even while seeming to confine himself to a single color: white. His death on Friday, in New York, at the age of 88, brings to a close one of the singular careers in postwar America art.

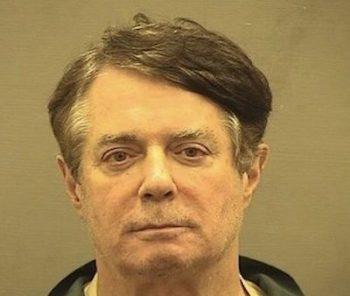

Over the course of the more than half-century of relentless experimentation that followed, Ryman radically expanded the possibilities of abstract painting, continuously rethinking how it could be made and what it could look like, even while seeming to confine himself to a single color: white. His death on Friday, in New York, at the age of 88, brings to a close one of the singular careers in postwar America art. Yet one cluster of texts never entered public discourse in the same way. For eight months after these texts were released online — an eon, in internet time — no one wrote about them. The sleaziest gossip outlets, which enthusiastically published other dirty details about Manafort (including his membership in BDSM sex clubs), wouldn’t touch it. Deep transparency conspiracy theorists didn’t Tweet about it. A

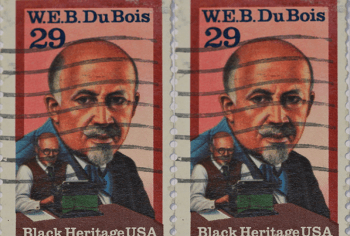

Yet one cluster of texts never entered public discourse in the same way. For eight months after these texts were released online — an eon, in internet time — no one wrote about them. The sleaziest gossip outlets, which enthusiastically published other dirty details about Manafort (including his membership in BDSM sex clubs), wouldn’t touch it. Deep transparency conspiracy theorists didn’t Tweet about it. A  February 1951 was a busy month for W. E. B. Du Bois, who turned eighty-three and threw himself a huge birthday party to raise funds for African decolonization. He also married his second wife, the leftist writer Shirley Graham, in what the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper called the wedding of the year. And he was indicted, arrested, and arraigned in federal court as an agent of the Soviet Union because he had circulated a petition protesting nuclear weapons. The Justice Department saw Du Bois’s petition as a threat to national security. They thought it was communist propaganda meant to encourage American pacifism in the face of Soviet aggression. They put Du Bois on trial in order to brand him as “un-American,” to use the language of Joe McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee. Du Bois was not in fact a Soviet agent. He was an American citizen using his First Amendment rights to protest nuclear weapons on his own behalf. A federal judge acquitted him because prosecutors failed to present any evidence.

February 1951 was a busy month for W. E. B. Du Bois, who turned eighty-three and threw himself a huge birthday party to raise funds for African decolonization. He also married his second wife, the leftist writer Shirley Graham, in what the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper called the wedding of the year. And he was indicted, arrested, and arraigned in federal court as an agent of the Soviet Union because he had circulated a petition protesting nuclear weapons. The Justice Department saw Du Bois’s petition as a threat to national security. They thought it was communist propaganda meant to encourage American pacifism in the face of Soviet aggression. They put Du Bois on trial in order to brand him as “un-American,” to use the language of Joe McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee. Du Bois was not in fact a Soviet agent. He was an American citizen using his First Amendment rights to protest nuclear weapons on his own behalf. A federal judge acquitted him because prosecutors failed to present any evidence. One thing is common among all the good and great writers: a deep sympathy with man; an ability to view and understand the various aspects of his character and the complex situations of his psychology; and a desire to see life as elegant, pure and pretty, fruit-laden and blooming. Humans do work of various kinds to maintain their personal and social life and for the satisfaction of their desires and instincts; and establish mutual bonds and relationships. They make things, provisions and tools, different laws for their use, ownership and distribution, and principles and codes of conduct.

One thing is common among all the good and great writers: a deep sympathy with man; an ability to view and understand the various aspects of his character and the complex situations of his psychology; and a desire to see life as elegant, pure and pretty, fruit-laden and blooming. Humans do work of various kinds to maintain their personal and social life and for the satisfaction of their desires and instincts; and establish mutual bonds and relationships. They make things, provisions and tools, different laws for their use, ownership and distribution, and principles and codes of conduct. I remember One Hundred Years of Solitude on my parents’ bookshelf when I was a child: it was the “one hundred years” that put me off: it sounded like it must be something to do with history, very boring history; “solitude” didn’t sound like much fun either. I imagined it was about a man being alone for a hundred years, talking endlessly to himself in the manner of “To be or not to be?” There was also Love in the Time of Cholera, which I assumed must be about cholera. (There were many medical textbooks in the house, both my parents being doctors. I had often leafed through The Handbook of Tropical Infectious Diseases, and knew all about cholera.)

I remember One Hundred Years of Solitude on my parents’ bookshelf when I was a child: it was the “one hundred years” that put me off: it sounded like it must be something to do with history, very boring history; “solitude” didn’t sound like much fun either. I imagined it was about a man being alone for a hundred years, talking endlessly to himself in the manner of “To be or not to be?” There was also Love in the Time of Cholera, which I assumed must be about cholera. (There were many medical textbooks in the house, both my parents being doctors. I had often leafed through The Handbook of Tropical Infectious Diseases, and knew all about cholera.) In the near future, we will be in possession of genetic engineering technology which allows us to move genes precisely and massively from one species to another. Careless or commercially driven use of this technology could make the concept of species meaningless, mixing up populations and mating systems so that much of the individuality of species would be lost. Cultural evolution gave us the power to do this. To preserve our wildlife as nature evolved it, the machinery of biological evolution must be protected from the homogenizing effects of cultural evolution.

In the near future, we will be in possession of genetic engineering technology which allows us to move genes precisely and massively from one species to another. Careless or commercially driven use of this technology could make the concept of species meaningless, mixing up populations and mating systems so that much of the individuality of species would be lost. Cultural evolution gave us the power to do this. To preserve our wildlife as nature evolved it, the machinery of biological evolution must be protected from the homogenizing effects of cultural evolution. Ever since the election of Donald Trump, pundits and scholars have been sounding the alarm over the

Ever since the election of Donald Trump, pundits and scholars have been sounding the alarm over the  Religious fictionalists hold that the contentious claims of religion, such as “God exists” or “Jesus rose from the dead” are all, strictly speaking, false. They nonetheless think that religious discourse, as part of the practice in which such discourse is embedded, has a pragmatic value that justifies its use. To put it simply: God is a useful fiction. In fact, fictionalism is popular in many areas of philosophy. There are, for example, moral fictionalists and mathematical fictionalists, who think that there are pragmatic benefits to using moral/mathematical language even though such discourse fails to correspond to a genuine reality (there are, on these views, no such things as goodness or the number 9, any more than there are dragons or witches). Religious fictionalists merely extend this approach to the statements of religion.

Religious fictionalists hold that the contentious claims of religion, such as “God exists” or “Jesus rose from the dead” are all, strictly speaking, false. They nonetheless think that religious discourse, as part of the practice in which such discourse is embedded, has a pragmatic value that justifies its use. To put it simply: God is a useful fiction. In fact, fictionalism is popular in many areas of philosophy. There are, for example, moral fictionalists and mathematical fictionalists, who think that there are pragmatic benefits to using moral/mathematical language even though such discourse fails to correspond to a genuine reality (there are, on these views, no such things as goodness or the number 9, any more than there are dragons or witches). Religious fictionalists merely extend this approach to the statements of religion. For me, Eastern Europe is a continent of ruins, a relic of a fallen empire.

For me, Eastern Europe is a continent of ruins, a relic of a fallen empire. I wondered whether Shelley’s misfortunes in the 1820s were also responsible for the novel’s obsession with loneliness. Everyone in the story, in particular the three men who take control of the narrative in turn—if the monster can be called a man—longs desperately for companionship. Walton writes, in his second letter posted from Archangel, a Russian port on the White Sea: “I have one want which I have never yet been able to satisfy, and the absence of the object of which I now feel as a most severe evil, I have no friend, Margaret … You may deem me romantic, my dear sister, but I bitterly feel the want of a friend.” He does not expect to find one on the ocean, but he does, in Victor Frankenstein. Frankenstein left his lifelong friends behind to attend university; it may be his isolation that leads him astray. The monster’s loneliness is especially keen. He calls the poor cottagers, who are ignorant of his existence, his friends: “When they were unhappy, I felt depressed; when they rejoiced, I sympathized in their joys. I saw few human beings besides them, and if any other happened to enter the cottage, their harsh manners and rude gait only enhanced to me the superior accomplishments of my friends.”

I wondered whether Shelley’s misfortunes in the 1820s were also responsible for the novel’s obsession with loneliness. Everyone in the story, in particular the three men who take control of the narrative in turn—if the monster can be called a man—longs desperately for companionship. Walton writes, in his second letter posted from Archangel, a Russian port on the White Sea: “I have one want which I have never yet been able to satisfy, and the absence of the object of which I now feel as a most severe evil, I have no friend, Margaret … You may deem me romantic, my dear sister, but I bitterly feel the want of a friend.” He does not expect to find one on the ocean, but he does, in Victor Frankenstein. Frankenstein left his lifelong friends behind to attend university; it may be his isolation that leads him astray. The monster’s loneliness is especially keen. He calls the poor cottagers, who are ignorant of his existence, his friends: “When they were unhappy, I felt depressed; when they rejoiced, I sympathized in their joys. I saw few human beings besides them, and if any other happened to enter the cottage, their harsh manners and rude gait only enhanced to me the superior accomplishments of my friends.”