Megan Scudellari in Nature:

When Craig Crews first managed to make proteins disappear on command with a bizarre new compound, the biochemist says that he considered it a “parlour trick”, a “cute chemical curiosity”. Today, that cute trick is driving billions of US dollars in investment from pharmaceutical companies such as Roche, Pfizer, Merck, Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline. “I think you can infer that pretty much every company has programmes in this area,” says Raymond Deshaies, senior vice-president of global research at Amgen in Thousand Oaks, California, and one of Crews’s early collaborators. The drug strategy, called targeted protein degradation, capitalizes on the cell’s natural system for clearing unwanted or damaged proteins. These protein degraders take many forms, but the type that is heading for clinical trials this year is one that Crews, based at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, has spent more than 20 years developing: proteolysis-targeting chimaeras, or PROTACs.

When Craig Crews first managed to make proteins disappear on command with a bizarre new compound, the biochemist says that he considered it a “parlour trick”, a “cute chemical curiosity”. Today, that cute trick is driving billions of US dollars in investment from pharmaceutical companies such as Roche, Pfizer, Merck, Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline. “I think you can infer that pretty much every company has programmes in this area,” says Raymond Deshaies, senior vice-president of global research at Amgen in Thousand Oaks, California, and one of Crews’s early collaborators. The drug strategy, called targeted protein degradation, capitalizes on the cell’s natural system for clearing unwanted or damaged proteins. These protein degraders take many forms, but the type that is heading for clinical trials this year is one that Crews, based at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, has spent more than 20 years developing: proteolysis-targeting chimaeras, or PROTACs.

Large and unwieldy, PROTACs defy conventional wisdom on what a drug should be. But they also raise the possibility of tackling some of the most indomitable diseases around. Because they destroy rather than inhibit proteins, and can bind to them where other drugs can’t, protein degraders could conceivably be used to go after targets that drug developers have long considered ‘undruggable’: cancer-fuelling villains such as the protein MYC, or the tau protein that tangles up in Alzheimer’s disease.

More here.

I stopped listening to music and watching TV in my 20s. It sounds extreme, but I did it because I thought they would just distract me from thinking about software. That blackout period lasted only about five years, and these days I’m a huge fan of TV shows like Narcos and listen to a lot of U2, Willie Nelson, and the Beatles.

I stopped listening to music and watching TV in my 20s. It sounds extreme, but I did it because I thought they would just distract me from thinking about software. That blackout period lasted only about five years, and these days I’m a huge fan of TV shows like Narcos and listen to a lot of U2, Willie Nelson, and the Beatles. In February, Time Out Dubai ecstatically

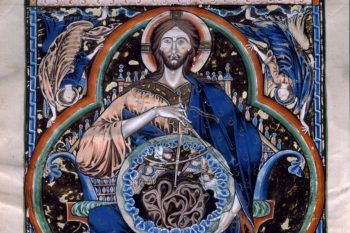

In February, Time Out Dubai ecstatically  Despite the spread of secularism in the West, rising levels of religious belief in the world as a whole have become incontrovertible. Three-quarters of humanity profess a faith; the figure is projected to reach 80 per cent by 2050 – not just because believers tend to have more children, but also through the spread of democracy. Significant, too, is the growing prominence of post-secular thinking in several disciplines. Things looked very different as recently as the 1980s. Influential commentators assumed that mainstream religion would fade away within a few generations; anglophone theologians, to name only one group, were often intellectually insecure. The turning of the tide is a significant chapter in the history of ideas meriting a full-length study of its own. Its main conclusions are worth outlining. The scales of debate on whether religion does more harm than good will tilt a bit if the theistic picture looks more coherent on closer inspection than many had previously thought, and naturalism – the thesis that everything is ultimately explicable in the language of natural science – less plausible as a consequence.

Despite the spread of secularism in the West, rising levels of religious belief in the world as a whole have become incontrovertible. Three-quarters of humanity profess a faith; the figure is projected to reach 80 per cent by 2050 – not just because believers tend to have more children, but also through the spread of democracy. Significant, too, is the growing prominence of post-secular thinking in several disciplines. Things looked very different as recently as the 1980s. Influential commentators assumed that mainstream religion would fade away within a few generations; anglophone theologians, to name only one group, were often intellectually insecure. The turning of the tide is a significant chapter in the history of ideas meriting a full-length study of its own. Its main conclusions are worth outlining. The scales of debate on whether religion does more harm than good will tilt a bit if the theistic picture looks more coherent on closer inspection than many had previously thought, and naturalism – the thesis that everything is ultimately explicable in the language of natural science – less plausible as a consequence. No composer exerted a greater influence on the music that came after him than Johann Sebastian Bach, who was born on this date in 1685. As we celebrate his birthday, let us consider one distinctive way in which composers have paid homage to the master: by using Bach’s name itself as a musical motif. In German nomenclature, the note (and key of) B flat is represented by the letter B; B natural is represented by the letter H. A and C are just as they are, so to spell out Bach’s surname in musical form yields a four-note motif consisting of B flat, A, C, and B. Bach himself used the motif (a kind of autograph stamp, sometimes surreptitious, sometimes not), and many others followed his lead: Robert Schumann, Franz Liszt, Max Reger, Arnold Schoenberg, Francis Poulenc, Anton Webern, Arvo Pärt, Krzysztof Penderecki, and Alfred Schnittke among them. One of the most imaginative uses of the motif came from a composer who is too often overlooked by music critics but who happened to be one of the most innovative and arresting voices in 20th-century music, Bruno Maderna.

No composer exerted a greater influence on the music that came after him than Johann Sebastian Bach, who was born on this date in 1685. As we celebrate his birthday, let us consider one distinctive way in which composers have paid homage to the master: by using Bach’s name itself as a musical motif. In German nomenclature, the note (and key of) B flat is represented by the letter B; B natural is represented by the letter H. A and C are just as they are, so to spell out Bach’s surname in musical form yields a four-note motif consisting of B flat, A, C, and B. Bach himself used the motif (a kind of autograph stamp, sometimes surreptitious, sometimes not), and many others followed his lead: Robert Schumann, Franz Liszt, Max Reger, Arnold Schoenberg, Francis Poulenc, Anton Webern, Arvo Pärt, Krzysztof Penderecki, and Alfred Schnittke among them. One of the most imaginative uses of the motif came from a composer who is too often overlooked by music critics but who happened to be one of the most innovative and arresting voices in 20th-century music, Bruno Maderna. Okwui’s art world looked more like the world itself. But this was no occasion for self-congratulation, much less for exercises in the sterile American rhetoric of ‘inclusion’, which he disdained. His project was to decolonise the art world: not to make it more ‘diverse’ but to redistribute power inside it.

Okwui’s art world looked more like the world itself. But this was no occasion for self-congratulation, much less for exercises in the sterile American rhetoric of ‘inclusion’, which he disdained. His project was to decolonise the art world: not to make it more ‘diverse’ but to redistribute power inside it. Every

Every  It is a commonplace that we live in a time of political polarization and culture war, but if culture is considered not in terms of left and right but as a set of attitudes toward the arts, then, at least among people who pay attention to the arts, we live in an era that cherishes consensus. The first consensus is that ours is an age of plenty. There is so much to watch, to hear, to see, to read, that we should count ourselves lucky. We are cursed only by too many options and too little time to consume all the wonderful things on offer. The cultural consumer (Alex or Wendy) is therefore best served by entities that point them to the right products. Find the right products, and you can undergo an experience you can share with your friends, even the thousands of them you’ve never met. Of course, individual people have preferences and interests, so filters, digital or human, will be required. Everyone will have favorites. What’s superfluous is the negative opinion. The negative opinion wastes Alex and Wendy’s time.

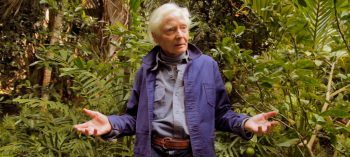

It is a commonplace that we live in a time of political polarization and culture war, but if culture is considered not in terms of left and right but as a set of attitudes toward the arts, then, at least among people who pay attention to the arts, we live in an era that cherishes consensus. The first consensus is that ours is an age of plenty. There is so much to watch, to hear, to see, to read, that we should count ourselves lucky. We are cursed only by too many options and too little time to consume all the wonderful things on offer. The cultural consumer (Alex or Wendy) is therefore best served by entities that point them to the right products. Find the right products, and you can undergo an experience you can share with your friends, even the thousands of them you’ve never met. Of course, individual people have preferences and interests, so filters, digital or human, will be required. Everyone will have favorites. What’s superfluous is the negative opinion. The negative opinion wastes Alex and Wendy’s time. Let’s say, for sake of argument, that you don’t believe in God or the supernatural. Is there still a place for talking about transcendence, the sacred, and meaning in life? Some of the above, but not all? Today’s guest, Alan Lightman, brings a unique perspective to these questions, as someone who has worked within both the sciences and the humanities at the highest level. In his most recent book, Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine, he makes the case that naturalists should take transcendence seriously. We talk about the assumptions underlying scientific practice, and the implications that the finitude of our lives has for our search for meaning.

Let’s say, for sake of argument, that you don’t believe in God or the supernatural. Is there still a place for talking about transcendence, the sacred, and meaning in life? Some of the above, but not all? Today’s guest, Alan Lightman, brings a unique perspective to these questions, as someone who has worked within both the sciences and the humanities at the highest level. In his most recent book, Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine, he makes the case that naturalists should take transcendence seriously. We talk about the assumptions underlying scientific practice, and the implications that the finitude of our lives has for our search for meaning. Decades ago, economists developed solutions – or variants on the same solution – to the problem of pollution, the key being the imposition of a price on the generation of pollutants such as carbon dioxide (CO2). The idea was to make visible, and accountable, the true environmental costs of any production process.

Decades ago, economists developed solutions – or variants on the same solution – to the problem of pollution, the key being the imposition of a price on the generation of pollutants such as carbon dioxide (CO2). The idea was to make visible, and accountable, the true environmental costs of any production process.

If you tell me to calm down, I probably won’t. The same goes for: “be reasonable,” “get over it already,” “you’re overreacting,” “it was just a joke,” “it’s not such a big deal.” When someone minimizes my feelings, my self-protective reflexes kick in. My body, my mind, my job, my interests, my talents—these are all “mine”—but nothing has quite the power to declare itself as “mine” as a passionate emotion does. When waves of anger or love or grief wash over me, that emotion feels like life itself. It wells up from an innermost core, like my voice, which it usually inflects. And so if you move to tamp it down, I parry by shutting you out: I erect walls around my sanctum sanctorum, to shield the flame of my passion—my life—from your soul-quenching intrusions. Who are you to tell me what I can and cannot feel?!

If you tell me to calm down, I probably won’t. The same goes for: “be reasonable,” “get over it already,” “you’re overreacting,” “it was just a joke,” “it’s not such a big deal.” When someone minimizes my feelings, my self-protective reflexes kick in. My body, my mind, my job, my interests, my talents—these are all “mine”—but nothing has quite the power to declare itself as “mine” as a passionate emotion does. When waves of anger or love or grief wash over me, that emotion feels like life itself. It wells up from an innermost core, like my voice, which it usually inflects. And so if you move to tamp it down, I parry by shutting you out: I erect walls around my sanctum sanctorum, to shield the flame of my passion—my life—from your soul-quenching intrusions. Who are you to tell me what I can and cannot feel?!

Look at me, the con artist says. Watch closely so you can see everything I’m doing. We can’t, of course, because we’re not meant to. Yet we fall for frauds because we so want what they promise to be true: easy money, better solutions, painlessness and efficiency. Elizabeth Holmes, the woman at the center of the Theranos scandal and the central subject of “The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley,” dangled all of these offers in front of the world using showy language, a moving personal story and the appearance of expertise and vision. She parlayed her youth, her intellect, her unwavering commitment to success and her connections to raise hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital out of air. By the time she had scammed powerful politicians, wealthy media magnates and an entire drug store chain, she’d amassed enough money to become, for a short time, the world’s youngest self-made billionaire. As in truly self-made, not Kylie Jenner self-made. Holmes did not benefit from the cushion of fame or industry wealth. What she had was a story.

Look at me, the con artist says. Watch closely so you can see everything I’m doing. We can’t, of course, because we’re not meant to. Yet we fall for frauds because we so want what they promise to be true: easy money, better solutions, painlessness and efficiency. Elizabeth Holmes, the woman at the center of the Theranos scandal and the central subject of “The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley,” dangled all of these offers in front of the world using showy language, a moving personal story and the appearance of expertise and vision. She parlayed her youth, her intellect, her unwavering commitment to success and her connections to raise hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital out of air. By the time she had scammed powerful politicians, wealthy media magnates and an entire drug store chain, she’d amassed enough money to become, for a short time, the world’s youngest self-made billionaire. As in truly self-made, not Kylie Jenner self-made. Holmes did not benefit from the cushion of fame or industry wealth. What she had was a story. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is typically described by the problems it presents. It is known as a neurological disorder, marked by distractibility, impulsivity and hyperactivity, which begins in childhood and persists in adults. And, indeed, ADHD may have

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is typically described by the problems it presents. It is known as a neurological disorder, marked by distractibility, impulsivity and hyperactivity, which begins in childhood and persists in adults. And, indeed, ADHD may have