Scott Alexander in Slate Star Codex:

Let’s review how the pharmaceutical industry works: a company discovers and patents a potentially exciting new drug. They spend tens of millions of dollars proving safety and efficacy to the FDA. The FDA rewards them with a 10ish year monopoly on the drug, during which they can charge whatever ridiculous price they want. This isn’t a great system, but at least we get new medicines sometimes.

how the pharmaceutical industry works: a company discovers and patents a potentially exciting new drug. They spend tens of millions of dollars proving safety and efficacy to the FDA. The FDA rewards them with a 10ish year monopoly on the drug, during which they can charge whatever ridiculous price they want. This isn’t a great system, but at least we get new medicines sometimes.

Occasionally people discover that an existing chemical treats an illness, without the chemical having been discovered and patented by a pharmaceutical company. In this case, whoever spends tens of millions of dollars proving it works to the FDA may not get a monopoly on the drug and the right to sell it for ridiculous prices. So nobody spends tens of millions of dollars proving it works to the FDA, and so it risks never getting approved.

The usual solution is for some pharma company to make some tiny irrelevant change to the existing chemical, and patent this new chemical as an “exciting discovery” they just made. Everyone goes along with the ruse, the company spends tens of millions of dollars pushing it through FDA trials, it gets approved, and they charge ridiculous prices for ten years. I wouldn’t quite call this “the system works”, but again, at least we get new medicines.

Twenty years ago, people noticed that ketamine treated depression. Alas, ketamine already existed – it’s an anaesthetic and a popular recreational drug – so pharma companies couldn’t patent it and fund FDA trials, so it couldn’t get approved by the FDA for depression.

More here.

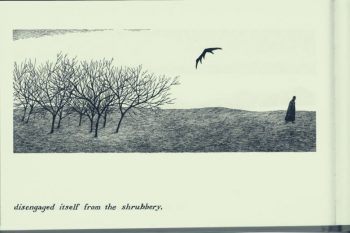

With its somewhat whimsical skulls and bats, Gorey’s more accessible work has all the trimmings of Gothic Lite, part of the same cultural wave that has made H. P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu into a popular plush toy. It tends to be set in a waveringly Victorian-Edwardian fin-de-siècle, or a louche and sometimes sinister vision of the 1920s. As Dery notes, Gorey’s retro negativity is partly “a code for signaling a conscientious objection to the present” and its crass positivity (its “Trumpian vulgarity”, as Dery calls it). Gorey’s friend Alison Lurie sees his fascination with funereal Victorianism as a reaction to the 1950s ethos according to which “everything was wonderful and we lived forever and the sun was shining”; and the Washington Post writer Henry Allen described him, in an obituary appreciation, as having “reached deeper into the educated American psyche” than Charles Addams, with whom he was sometimes paired: for Allen, he defied “the clamorous Doris Day optimism rampant at the start of his career”. Another of Gorey’s sharpest commentators, Thomas Garvey, writing in a context of Queer Theory, has suggested that Gorey’s ironic perversity “allows his art to be re-purposed by heterosexuals into a tonic for the pressures of wholesomeness”.

With its somewhat whimsical skulls and bats, Gorey’s more accessible work has all the trimmings of Gothic Lite, part of the same cultural wave that has made H. P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu into a popular plush toy. It tends to be set in a waveringly Victorian-Edwardian fin-de-siècle, or a louche and sometimes sinister vision of the 1920s. As Dery notes, Gorey’s retro negativity is partly “a code for signaling a conscientious objection to the present” and its crass positivity (its “Trumpian vulgarity”, as Dery calls it). Gorey’s friend Alison Lurie sees his fascination with funereal Victorianism as a reaction to the 1950s ethos according to which “everything was wonderful and we lived forever and the sun was shining”; and the Washington Post writer Henry Allen described him, in an obituary appreciation, as having “reached deeper into the educated American psyche” than Charles Addams, with whom he was sometimes paired: for Allen, he defied “the clamorous Doris Day optimism rampant at the start of his career”. Another of Gorey’s sharpest commentators, Thomas Garvey, writing in a context of Queer Theory, has suggested that Gorey’s ironic perversity “allows his art to be re-purposed by heterosexuals into a tonic for the pressures of wholesomeness”. In June, 2015, Roberto Carlos Lange, who records as Helado Negro, released a single titled “Young, Latin and Proud.” Despite the bold title, the song sounded more like a flicker than like a flame. It was tranquil and soothing, with Lange singing gently, almost timidly, over a swaying synth line. His lyrics were addressed to a younger version of himself—someone searching for the language to make sense of his own story: “And you can only view you / With what you got / You don’t have to pretend / That you got to know more / ’Cause you are young, Latin, and proud.”

In June, 2015, Roberto Carlos Lange, who records as Helado Negro, released a single titled “Young, Latin and Proud.” Despite the bold title, the song sounded more like a flicker than like a flame. It was tranquil and soothing, with Lange singing gently, almost timidly, over a swaying synth line. His lyrics were addressed to a younger version of himself—someone searching for the language to make sense of his own story: “And you can only view you / With what you got / You don’t have to pretend / That you got to know more / ’Cause you are young, Latin, and proud.” Sex is Johnson’s true subject. She respects its power and repeatedly enacts a woman’s right to sexual realisation. Physical contact is something so fraught and regulated as to be inherently violent. Violence can come out of detachment too: ‘He dragged at the vee of her dress and put his fingers to her breasts.’ Elsie is intent on discovering the facts of life and perturbed by ‘the knitting of her flesh’ when she passes a couple kissing under a tree. When she acquires a boyfriend, Roly, he says he’ll take her clothes off and thrash her if she looks at someone else. Elsie counters that she’d rather like that before realising she has ‘said something very wrong’. She lies down with him but resists. On the way home Roly stops off to see Mrs Maginnis. He orders Nietzsche and Freud in the local library, and arranges a date with the librarian. He blames Elsie’s resistance on the ‘whole social system … When a man loves a woman, he ought to be able to sleep with her right away, and then there would be no repressions or inhibitions.’ When they finally get married and go to bed, ‘there was no fear in her, nor love, only a great loneliness.’

Sex is Johnson’s true subject. She respects its power and repeatedly enacts a woman’s right to sexual realisation. Physical contact is something so fraught and regulated as to be inherently violent. Violence can come out of detachment too: ‘He dragged at the vee of her dress and put his fingers to her breasts.’ Elsie is intent on discovering the facts of life and perturbed by ‘the knitting of her flesh’ when she passes a couple kissing under a tree. When she acquires a boyfriend, Roly, he says he’ll take her clothes off and thrash her if she looks at someone else. Elsie counters that she’d rather like that before realising she has ‘said something very wrong’. She lies down with him but resists. On the way home Roly stops off to see Mrs Maginnis. He orders Nietzsche and Freud in the local library, and arranges a date with the librarian. He blames Elsie’s resistance on the ‘whole social system … When a man loves a woman, he ought to be able to sleep with her right away, and then there would be no repressions or inhibitions.’ When they finally get married and go to bed, ‘there was no fear in her, nor love, only a great loneliness.’ Three Saudi women’s rights activists whose arrests last year have been condemned worldwide are being honored by PEN America. Nouf Abdulaziz, Loujain al-Hathloul, and Eman al-Nafjan have won the PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award, the literary and human rights organization announced Thursday. The award was established in 1987 and is given to writers imprisoned for their work, with previous recipients coming from Ukraine, Egypt and Ethiopia among other countries.

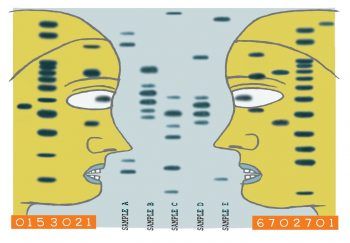

Three Saudi women’s rights activists whose arrests last year have been condemned worldwide are being honored by PEN America. Nouf Abdulaziz, Loujain al-Hathloul, and Eman al-Nafjan have won the PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award, the literary and human rights organization announced Thursday. The award was established in 1987 and is given to writers imprisoned for their work, with previous recipients coming from Ukraine, Egypt and Ethiopia among other countries. We call for a global moratorium on all clinical uses of human germline editing — that is, changing heritable DNA (in sperm, eggs or embryos) to make genetically modified children. By ‘global moratorium’, we do not mean a permanent ban. Rather, we call for the establishment of an international framework in which nations, while retaining the right to make their own decisions, voluntarily commit to not approve any use of clinical germline editing unless certain conditions are met. To begin with, there should be a fixed period during which no clinical uses of germline editing whatsoever are allowed. As well as allowing for discussions about the technical, scientific, medical, societal, ethical and moral issues that must be considered before germline editing is permitted, this period would provide time to establish an international framework.

We call for a global moratorium on all clinical uses of human germline editing — that is, changing heritable DNA (in sperm, eggs or embryos) to make genetically modified children. By ‘global moratorium’, we do not mean a permanent ban. Rather, we call for the establishment of an international framework in which nations, while retaining the right to make their own decisions, voluntarily commit to not approve any use of clinical germline editing unless certain conditions are met. To begin with, there should be a fixed period during which no clinical uses of germline editing whatsoever are allowed. As well as allowing for discussions about the technical, scientific, medical, societal, ethical and moral issues that must be considered before germline editing is permitted, this period would provide time to establish an international framework.

One night in November 1999, a 26-year-old woman was raped in a parking lot in Grand Rapids, Mich. Police officers managed to get the perpetrator’s DNA from a semen sample, but it matched no one in their databases.

One night in November 1999, a 26-year-old woman was raped in a parking lot in Grand Rapids, Mich. Police officers managed to get the perpetrator’s DNA from a semen sample, but it matched no one in their databases. At Oxford University’s Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences, which he heads, Carr was conducting a clinical trial of decompression surgery, to assess its effectiveness. He explained to Brennan that if she agreed to participate she would be randomly assigned to one of three groups. The first would receive regular surgery. The second set would get “placebo surgery”, with all the surgical procedures identical to the normal operation except that no bone or tissue would be removed. Patients in these two groups would not know if they’d had the real or sham surgery. The third group would receive no treatment.

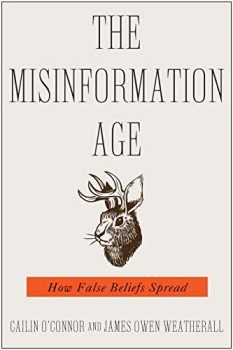

At Oxford University’s Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences, which he heads, Carr was conducting a clinical trial of decompression surgery, to assess its effectiveness. He explained to Brennan that if she agreed to participate she would be randomly assigned to one of three groups. The first would receive regular surgery. The second set would get “placebo surgery”, with all the surgical procedures identical to the normal operation except that no bone or tissue would be removed. Patients in these two groups would not know if they’d had the real or sham surgery. The third group would receive no treatment. Since early 2016, in the lead-up to the U.S. presidential election and the Brexit vote in the UK, there has been a growing appreciation of the role that misinformation and false beliefs have come to play in major political decisions in Western democracies. (What we have in minds are beliefs such as that vaccines cause autism, that anthropogenic climate change is not real, that the UK pays exorbitant fees to the EU that could be readily redirected to domestic programs, or that genetically modified foods are generally harmful.)

Since early 2016, in the lead-up to the U.S. presidential election and the Brexit vote in the UK, there has been a growing appreciation of the role that misinformation and false beliefs have come to play in major political decisions in Western democracies. (What we have in minds are beliefs such as that vaccines cause autism, that anthropogenic climate change is not real, that the UK pays exorbitant fees to the EU that could be readily redirected to domestic programs, or that genetically modified foods are generally harmful.) In 2010, a precious metals blogger called Peter Boehringer posted an image of Karl Marx’s head floating over Frankfurt, the home of the European Central Bank. Like many online “gold bugs,” his message reflected the belief that currencies without the backing of gold amount to “monetary socialism” and pave the way to government overreach and eventual economic collapse. Boehringer now sits in the German Bundestag for the Alternative for Germany Party (AfD), and chairs the parliament’s budget committee.

In 2010, a precious metals blogger called Peter Boehringer posted an image of Karl Marx’s head floating over Frankfurt, the home of the European Central Bank. Like many online “gold bugs,” his message reflected the belief that currencies without the backing of gold amount to “monetary socialism” and pave the way to government overreach and eventual economic collapse. Boehringer now sits in the German Bundestag for the Alternative for Germany Party (AfD), and chairs the parliament’s budget committee. James Purdy

James Purdy A

A While a computer is useless after just a few years or an iPhone goes out of date — planned obsolescence, of course — a brick can last for centuries; it’s the best technology we have ever developed.

While a computer is useless after just a few years or an iPhone goes out of date — planned obsolescence, of course — a brick can last for centuries; it’s the best technology we have ever developed. On April 7, 2003, less than three weeks into America’s invasion of Iraq, Bruno Latour worried aloud, in a lecture at Stanford, that scholars and intellectuals had themselves become too combative. Under the circumstances, he asked, did it really help to take official accounts of reality as an enemy, aiming to expose the prejudice and ideology hidden behind supposedly objective facts? “Is it really the task of the humanities to add deconstruction to destruction?,” he wondered.

On April 7, 2003, less than three weeks into America’s invasion of Iraq, Bruno Latour worried aloud, in a lecture at Stanford, that scholars and intellectuals had themselves become too combative. Under the circumstances, he asked, did it really help to take official accounts of reality as an enemy, aiming to expose the prejudice and ideology hidden behind supposedly objective facts? “Is it really the task of the humanities to add deconstruction to destruction?,” he wondered.