John Mullan in The Guardian:

As we await the final season of Game of Thrones, curiosity settles on a single question: how will it end? Fan sites buzz with speculation about what the most convincing conclusion could be. Surely Jon Snow’s true lineage will be revealed to him? Won’t we have to find out the truth about Cersei’s pregnancy? Will the White Walkers finally be defeated? And above all, who will reign at the end? The makers of the series have set themselves a challenge: conjuring what the great literary critic Frank Kermode called “the sense of an ending”, and they can no longer rely on the original novels of George RR Martin.

As we await the final season of Game of Thrones, curiosity settles on a single question: how will it end? Fan sites buzz with speculation about what the most convincing conclusion could be. Surely Jon Snow’s true lineage will be revealed to him? Won’t we have to find out the truth about Cersei’s pregnancy? Will the White Walkers finally be defeated? And above all, who will reign at the end? The makers of the series have set themselves a challenge: conjuring what the great literary critic Frank Kermode called “the sense of an ending”, and they can no longer rely on the original novels of George RR Martin.

…The most extraordinary example is one of the best of all 19th-century novels, Great Expectations. For this story, which had been appearing in weekly instalments in his own magazine, All the Year Round, Dickens wrote one of the few unhappy endings of his career. In the first draft, Pip returns from years working abroad. He is walking down Piccadilly with the young son of Joe and Biddy, named Pip after him. A lady in a carriage summons him; it is Estella. She is now married to a doctor who lives in Shropshire: “I am greatly changed, I know; but I thought you would like to shake hands with Estella, too, Pip. Lift up that pretty child and let me kiss it!” (She supposed the child, I think, to be my child.) I was very glad afterwards to have had the interview; for, in her face and in her voice, and in her touch, she gave me the assurance, that suffering had been stronger than Miss Havisham’s teaching, and had given her a heart to understand what my heart used to be.

Piercingly, Dickens and his narrator allow Estella to depart on a misunderstanding: she believes that Pip has married and had a son – but in fact he is alone, his capacity for love cauterised by his experiences. He does not get Estella; he does not get anyone. When Dickens’s friend and fellow novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton read this he was horrified. What would the author’s loyal readers, who expected their usual happy ending, think? Dickens was persuaded to write a new ending, in which Estella is husbandless when she meets Pip again in the ruins of Satis House. This time the narrator sees “no shadow of a future parting” from the woman he loves. Dickens, who scanned his monthly or weekly sales with just the attention a TV producer might give to viewing figures, succumbed to fears about what his audience wanted. He scrapped a brilliant ending in favour of a merely serviceable one. Have the scriptwriters of Game of Thrones been worrying in a similar fashion about what their devotees want and expect? Or will they give us an ending as arbitrarily brutal as the world they have created?

More here.

These days, no less an authority than Sarah Huckabee Sanders, the White House press secretary, said recently that God

These days, no less an authority than Sarah Huckabee Sanders, the White House press secretary, said recently that God

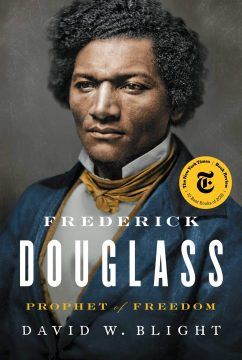

In Prophet of Freedom, Blight allows us to experience both the exuberance and the difficulties of a life acted out on stages. We see Douglass, as a small boy, gathering damp pages from a discarded Bible out of the gutter so he could learn how to read. We are shown the young, proud orator being shunted into filthy, segregated train cars even as he traveled to address throngs of adoring fans. And we are at the Rochester train station to see his wife Anna rush to meet him with a bundle of freshly ironed shirts before returning to her job making shoes, or caring for their five children, while the abolitionist rock star continued on his way. We are with him near the end of his life when he climbed a rocky crag near the Acropolis and lingered there to read St. Paul’s famous “Address to the Athenians,” in which the Apostle declared all people to be the “offspring” of God and that God “hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth.”

In Prophet of Freedom, Blight allows us to experience both the exuberance and the difficulties of a life acted out on stages. We see Douglass, as a small boy, gathering damp pages from a discarded Bible out of the gutter so he could learn how to read. We are shown the young, proud orator being shunted into filthy, segregated train cars even as he traveled to address throngs of adoring fans. And we are at the Rochester train station to see his wife Anna rush to meet him with a bundle of freshly ironed shirts before returning to her job making shoes, or caring for their five children, while the abolitionist rock star continued on his way. We are with him near the end of his life when he climbed a rocky crag near the Acropolis and lingered there to read St. Paul’s famous “Address to the Athenians,” in which the Apostle declared all people to be the “offspring” of God and that God “hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth.”

Eighty percent of women living in communist East Germany always reached orgasm during sex, according to the Hamburg magazine Neue Revue in 1990. For West German women that figure was only 63 percent. Those counterintuitive findings confirmed two earlier studies, which East German sex researchers had published in 1984 and 1988. Those had found East German women reported high levels of sexual satisfaction outpacing those in the West.

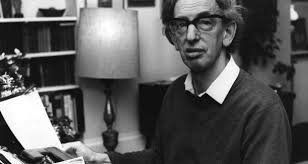

Eighty percent of women living in communist East Germany always reached orgasm during sex, according to the Hamburg magazine Neue Revue in 1990. For West German women that figure was only 63 percent. Those counterintuitive findings confirmed two earlier studies, which East German sex researchers had published in 1984 and 1988. Those had found East German women reported high levels of sexual satisfaction outpacing those in the West. Hayden White, the philosopher of history whose classic Metahistory (1973) has had an enduring influence on the humanities, died last year. In a career spanning half a century, White, whose appointments included Stanford University and the University of California at Santa Cruz, provoked, alarmed, and invigorated professional historians and lay readers alike. In Metahistory and elsewhere,

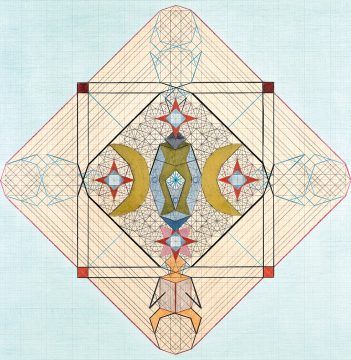

Hayden White, the philosopher of history whose classic Metahistory (1973) has had an enduring influence on the humanities, died last year. In a career spanning half a century, White, whose appointments included Stanford University and the University of California at Santa Cruz, provoked, alarmed, and invigorated professional historians and lay readers alike. In Metahistory and elsewhere,  Few people ever observed Emma Kunz, a Swiss alternative healer and artist, at work. One of the only accounts comes from a man called Anton Meier, who first met Kunz when his parents asked her to cure his childhood polio. Kunz was a spiritualist who used drawing as a way to divine the future. Meier recalled watching her in the early 1940s as she attempted to predict the outcome of a meeting between Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt:

Few people ever observed Emma Kunz, a Swiss alternative healer and artist, at work. One of the only accounts comes from a man called Anton Meier, who first met Kunz when his parents asked her to cure his childhood polio. Kunz was a spiritualist who used drawing as a way to divine the future. Meier recalled watching her in the early 1940s as she attempted to predict the outcome of a meeting between Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt: We left our E-Z Pass in the apartment. Stacy and I realize this only upon arriving at the mouth of the tunnel en route to the Weill Cornell ER. The gate fails to lift as we approach and we almost plow through it. The man at the tollbooth tries to reckon with us, incoherent and hysterical and blocking traffic.

We left our E-Z Pass in the apartment. Stacy and I realize this only upon arriving at the mouth of the tunnel en route to the Weill Cornell ER. The gate fails to lift as we approach and we almost plow through it. The man at the tollbooth tries to reckon with us, incoherent and hysterical and blocking traffic.

“This is actually one of the most surprising things in the whole history of public opinion,” says

“This is actually one of the most surprising things in the whole history of public opinion,” says

What has the Event Horizon Telescope actually seen?

What has the Event Horizon Telescope actually seen? Since the late 1990s, yearly rates of overdose deaths from legal “white market” opioids have consistently exceeded those from heroin. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, between 1999 and 2017, opioid overdoses killed nearly 400,000 people with 68 percent of those deaths linked to prescription medications. Moreover, as regulators and drug companies tightened controls on diversion and misuse after 2010, the American Society of Addiction Medicine determined that at least 80 percent of “new heroin users started out misusing prescription pain killers.” Some data sets point to even higher numbers. In response to a 2014 survey of people undergoing treatments for opioid addiction, 94 percent of people surveyed said that they turned to heroin because prescription opioids were “far more expensive and harder to obtain.”

Since the late 1990s, yearly rates of overdose deaths from legal “white market” opioids have consistently exceeded those from heroin. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, between 1999 and 2017, opioid overdoses killed nearly 400,000 people with 68 percent of those deaths linked to prescription medications. Moreover, as regulators and drug companies tightened controls on diversion and misuse after 2010, the American Society of Addiction Medicine determined that at least 80 percent of “new heroin users started out misusing prescription pain killers.” Some data sets point to even higher numbers. In response to a 2014 survey of people undergoing treatments for opioid addiction, 94 percent of people surveyed said that they turned to heroin because prescription opioids were “far more expensive and harder to obtain.” Almost nothing in this exhibition was created for aesthetic admiration alone. Whether it’s the way a Diné blanket’s lines break into daring geometric forms when placed across a person’s shoulders, or the transformation that a mask undergoes during a ritual, the full beauty of these objects has to be activated by the people who use them. One wishes those people were present. The more time one spends looking at the works on display at the Met, the more one suspects that they could only ever be seen as they are meant to be seen when used as they were meant to be used. Placed behind glass under the banner of “art,” they look abandoned.

Almost nothing in this exhibition was created for aesthetic admiration alone. Whether it’s the way a Diné blanket’s lines break into daring geometric forms when placed across a person’s shoulders, or the transformation that a mask undergoes during a ritual, the full beauty of these objects has to be activated by the people who use them. One wishes those people were present. The more time one spends looking at the works on display at the Met, the more one suspects that they could only ever be seen as they are meant to be seen when used as they were meant to be used. Placed behind glass under the banner of “art,” they look abandoned. Was

Was  Nowadays, not many philosophers are prominent enough to get nicknames. In medieval times the practice was more popular. Every scholastic worth their salt had one: Bonaventure was the “seraphic doctor”, Aquinas the “angelic doctor”, Duns Scotus the “subtle doctor”, and so on. In the Islamic world, too, outstanding thinkers were honoured with such titles. Of these, none was more appropriate than al-shaykh al-raʾīs, which one might loosely translate as “the leading sage”. It was bestowed on Abū ʿAlī Ibn Sīnā (d.1037 AD), who was known to all those medieval scholastics by the Latinized name “Avicenna”. And not just known, but renowned. Avicenna is one of the few philosophers to have become a major influence on the development of a completely foreign philosophical culture. Once his works were translated into Latin he became second only to Aristotle as an inspiration for thirteenth-century medieval philosophy, and (thanks to his definitive medical summary the Canon, in Arabic Qānūn) second only to Galen as a source for medical knowledge in Europe.

Nowadays, not many philosophers are prominent enough to get nicknames. In medieval times the practice was more popular. Every scholastic worth their salt had one: Bonaventure was the “seraphic doctor”, Aquinas the “angelic doctor”, Duns Scotus the “subtle doctor”, and so on. In the Islamic world, too, outstanding thinkers were honoured with such titles. Of these, none was more appropriate than al-shaykh al-raʾīs, which one might loosely translate as “the leading sage”. It was bestowed on Abū ʿAlī Ibn Sīnā (d.1037 AD), who was known to all those medieval scholastics by the Latinized name “Avicenna”. And not just known, but renowned. Avicenna is one of the few philosophers to have become a major influence on the development of a completely foreign philosophical culture. Once his works were translated into Latin he became second only to Aristotle as an inspiration for thirteenth-century medieval philosophy, and (thanks to his definitive medical summary the Canon, in Arabic Qānūn) second only to Galen as a source for medical knowledge in Europe.