Feng and Gilbert in Nature:

Suitable protein targets are needed to develop new anticancer drug-based treatments. Writing in Nature, Behan et al.1 and Chan et al.2, and, in eLife, Lieb et al.3, report that certain tumours that have deficiencies in a type of DNA-repair process require an enzyme called Werner syndrome ATP-dependent helicase (WRN) for their survival. If inhibitors of WRN are found, such molecules might be promising drug candidates for further testing.

Suitable protein targets are needed to develop new anticancer drug-based treatments. Writing in Nature, Behan et al.1 and Chan et al.2, and, in eLife, Lieb et al.3, report that certain tumours that have deficiencies in a type of DNA-repair process require an enzyme called Werner syndrome ATP-dependent helicase (WRN) for their survival. If inhibitors of WRN are found, such molecules might be promising drug candidates for further testing.

Imagine a scenario in which scientists could perform an experiment that reveals how almost every gene in the human genome is dysregulated in cancer. Even better, what if such an investigation also offered a road map for how to select a target when trying to develop treatments that take aim at cancer cells, but are non-toxic to normal cells? A type of gene-editing technology called CRISPR–Cas9 enables just that in an approach termed functional genomics. Using this technique, the function of almost every gene in cell-based models of cancer (comprising human cells grown in vitro or in vivo animal models) can be perturbed, and the effect of each perturbation on cancer-cell survival can be measured.

CRISPR can be used to mutate, repress or activate any targeted human gene4,5. In functional genomics, gene function is assessed in a single experiment by growing a large number of cells and then perturbing one gene in each of the cells.

More here.

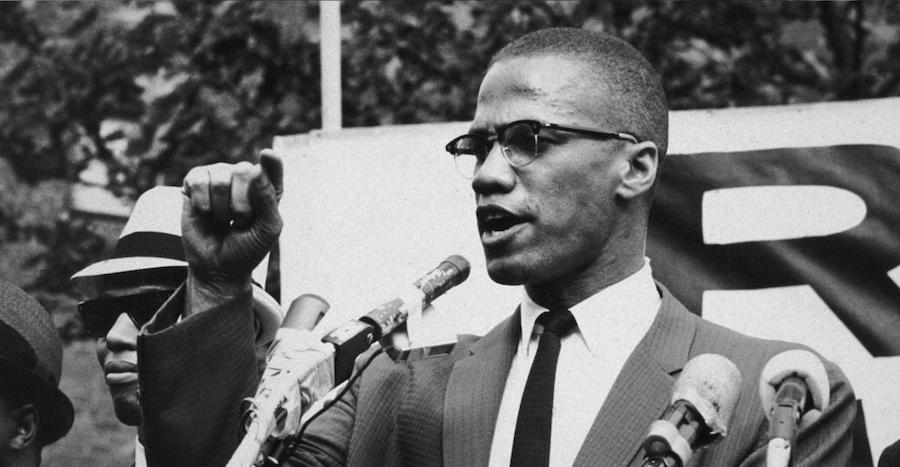

The video clip, slightly pixelated and shot in black and white, shows two men in the throes of laughter. One, white, leans closer, holding a microphone near his companion’s mouth. The other, Black, who was laughing with his head turned away, exposing a handsome set of teeth, composes himself, facing his interviewer, yet he is unable to hide his boyish smile.

The video clip, slightly pixelated and shot in black and white, shows two men in the throes of laughter. One, white, leans closer, holding a microphone near his companion’s mouth. The other, Black, who was laughing with his head turned away, exposing a handsome set of teeth, composes himself, facing his interviewer, yet he is unable to hide his boyish smile. In 1984, bacteria started showing up in patients’ blood at the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinic. Bacteria do not belong in the blood and such infections can quickly escalate into septic shock, a life threatening condition. Ultimately, blood samples revealed the culprit: A microbe that normally lives in the gut called

In 1984, bacteria started showing up in patients’ blood at the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinic. Bacteria do not belong in the blood and such infections can quickly escalate into septic shock, a life threatening condition. Ultimately, blood samples revealed the culprit: A microbe that normally lives in the gut called  The US government’s indictment of

The US government’s indictment of  Before I got sick, I’d been making plans for a place for public weeping, hoping to install in major cities a temple where anyone who needed it could get together to cry in good company and with the proper equipment. It would be a precisely imagined architecture of sadness: gargoyles made of night sweat, moldings made of longest minutes, support beams made of I-can’t-go-on-I-must-go-on. When planning the temple, I remembered the existence of people who hate those they call crybabies, and how they might respond with rage to a place full of distraught strangers—a place that exposed suffering as what is shared. It would have been something tremendous to offer those sufferers the exquisite comforts of stately marble troughs in which to collectivize their tears. But I never did this.

Before I got sick, I’d been making plans for a place for public weeping, hoping to install in major cities a temple where anyone who needed it could get together to cry in good company and with the proper equipment. It would be a precisely imagined architecture of sadness: gargoyles made of night sweat, moldings made of longest minutes, support beams made of I-can’t-go-on-I-must-go-on. When planning the temple, I remembered the existence of people who hate those they call crybabies, and how they might respond with rage to a place full of distraught strangers—a place that exposed suffering as what is shared. It would have been something tremendous to offer those sufferers the exquisite comforts of stately marble troughs in which to collectivize their tears. But I never did this. A “call to order” is taking place in political and intellectual life in Europe and abroad. This “rappel à l’ordre” has sounded before, in France after World War I, when it was directed at avant-garde artists, demanding that they put aside their experiments and create reassuring representations for those whose worlds had been torn apart by the war. But now it is directed toward those intellectuals, politicians, and citizens who still cling to the supposedly politically correct culture of postmodernism.

A “call to order” is taking place in political and intellectual life in Europe and abroad. This “rappel à l’ordre” has sounded before, in France after World War I, when it was directed at avant-garde artists, demanding that they put aside their experiments and create reassuring representations for those whose worlds had been torn apart by the war. But now it is directed toward those intellectuals, politicians, and citizens who still cling to the supposedly politically correct culture of postmodernism. The brain is a computer’ – this claim is as central to our scientific understanding of the mind as it is baffling to anyone who hears it. We are either told that this claim is just a metaphor or that it is in fact a precise, well-understood hypothesis. But it’s neither. We have clear reasons to think that it’s literally true that the brain is a computer, yet we don’t have any clear understanding of what this means. That’s a common story in science. To get the obvious out of the way: your brain is not made up of silicon chips and transistors. It doesn’t have separable components that are analogous to your computer’s hard drive, random-access memory (RAM) and central processing unit (CPU). But none of these things are essential to something’s being a computer. In fact, we don’t know what is essential for the brain to be a computer. Still, it is almost certainly true that it is one.

The brain is a computer’ – this claim is as central to our scientific understanding of the mind as it is baffling to anyone who hears it. We are either told that this claim is just a metaphor or that it is in fact a precise, well-understood hypothesis. But it’s neither. We have clear reasons to think that it’s literally true that the brain is a computer, yet we don’t have any clear understanding of what this means. That’s a common story in science. To get the obvious out of the way: your brain is not made up of silicon chips and transistors. It doesn’t have separable components that are analogous to your computer’s hard drive, random-access memory (RAM) and central processing unit (CPU). But none of these things are essential to something’s being a computer. In fact, we don’t know what is essential for the brain to be a computer. Still, it is almost certainly true that it is one.

A moonshot is on the rise on the Trump administration’s foreign policy agenda. At last month’s meeting of the National Space Council in Huntsville, Alabama, Vice President Mike Pence laid out an

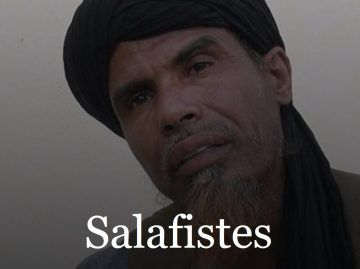

A moonshot is on the rise on the Trump administration’s foreign policy agenda. At last month’s meeting of the National Space Council in Huntsville, Alabama, Vice President Mike Pence laid out an  There’s a scene early on in the French documentary Salafistes (“Jihadists”) where the camera spans over a throng of people gathered in a village in northern Mali: the crowd is there to watch as the “Islamic Police” cut off a 25-year-old man’s hand. The shot zooms in as the young man, tethered in ropes around a chair, slumps over, unconscious, while his hand is sawed off with a small, serrated blade. Young boys in the background howl incoherently. In the next scene, the same young man is filmed lying in a bed cocooned by a lime green mosquito net, his severed limb wrapped in thick white bandages. “This is the application of sharia,” he tells the camera. “I committed a theft; in accordance with sharia my hand was amputated. Once I recover I will be purified and all my sins erased.” The trace of a drugged smile lingers across his face.

There’s a scene early on in the French documentary Salafistes (“Jihadists”) where the camera spans over a throng of people gathered in a village in northern Mali: the crowd is there to watch as the “Islamic Police” cut off a 25-year-old man’s hand. The shot zooms in as the young man, tethered in ropes around a chair, slumps over, unconscious, while his hand is sawed off with a small, serrated blade. Young boys in the background howl incoherently. In the next scene, the same young man is filmed lying in a bed cocooned by a lime green mosquito net, his severed limb wrapped in thick white bandages. “This is the application of sharia,” he tells the camera. “I committed a theft; in accordance with sharia my hand was amputated. Once I recover I will be purified and all my sins erased.” The trace of a drugged smile lingers across his face. I

I The explosion on April 26, 1986, at the V.I. Lenin, or Chernobyl, Atomic Energy Station in what was then the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic is thought to have “vaporized” one worker on the spot. Another 30, drenched in fatal doses of radiation, died gruesome, lingering deaths. As of 2005, as many as 5,000 additional cancer deaths were projected locally — among 25,000 extra cancer cases Europe-wide. Contamination rendered 1,838-plus square miles “uninhabitable.” And a spectral column of radioactive gases escaped into the atmosphere, setting people on edge from Stockholm to San Francisco. It was the worst nuclear accident in history and could have been far worse.

The explosion on April 26, 1986, at the V.I. Lenin, or Chernobyl, Atomic Energy Station in what was then the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic is thought to have “vaporized” one worker on the spot. Another 30, drenched in fatal doses of radiation, died gruesome, lingering deaths. As of 2005, as many as 5,000 additional cancer deaths were projected locally — among 25,000 extra cancer cases Europe-wide. Contamination rendered 1,838-plus square miles “uninhabitable.” And a spectral column of radioactive gases escaped into the atmosphere, setting people on edge from Stockholm to San Francisco. It was the worst nuclear accident in history and could have been far worse. Gdańsk was a city of the borders for many years, with a prevailing influence of German culture, German music, German language, because even the Polish proletariat when they came from the villages were Germanized, because with the German language they had better chances. But there used to be about 15%-20% Polish speaking people, 3% French people, 2% English people, 3.5% Russians, Scottish people as well, a lot of Dutch people; this was a typical city of the borders. This was over after the Polish partition of 1795. And then Gdańsk, which used to be a rich merchant city, a merchant emporium, became a provincial Prussian city. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, these were periods of the great German nationalisms, which end up with the crime of 1939, because most of the Polish people here were murdered at that time. Surprisingly, the Jews could leave. Because this used to be the Free City of Gdańsk, the so-called ‘Free City’, and the authorities of Gdańsk signed an agreement with the Jewish Community in 1939, more or less, perhaps one year earlier, and while the war was still going on, until 1940 the Jewish population was still leaving. So, the multicultural city was over with the Prussian partition. Then, after the war, 99% of the German population left, and Polish people from various parts of former Poland came, from burned-down Warsaw, from Wilno, or from the Eastern borders, from those parts; so, people only came back to the idea of multiculturalism, after 1989, with the end of Communism. But, if ever we speak of multiculturalism in Gdańsk, we speak of the distant past. Of course, it’s a very good example of something to reach for, but it’s a deep past.

Gdańsk was a city of the borders for many years, with a prevailing influence of German culture, German music, German language, because even the Polish proletariat when they came from the villages were Germanized, because with the German language they had better chances. But there used to be about 15%-20% Polish speaking people, 3% French people, 2% English people, 3.5% Russians, Scottish people as well, a lot of Dutch people; this was a typical city of the borders. This was over after the Polish partition of 1795. And then Gdańsk, which used to be a rich merchant city, a merchant emporium, became a provincial Prussian city. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, these were periods of the great German nationalisms, which end up with the crime of 1939, because most of the Polish people here were murdered at that time. Surprisingly, the Jews could leave. Because this used to be the Free City of Gdańsk, the so-called ‘Free City’, and the authorities of Gdańsk signed an agreement with the Jewish Community in 1939, more or less, perhaps one year earlier, and while the war was still going on, until 1940 the Jewish population was still leaving. So, the multicultural city was over with the Prussian partition. Then, after the war, 99% of the German population left, and Polish people from various parts of former Poland came, from burned-down Warsaw, from Wilno, or from the Eastern borders, from those parts; so, people only came back to the idea of multiculturalism, after 1989, with the end of Communism. But, if ever we speak of multiculturalism in Gdańsk, we speak of the distant past. Of course, it’s a very good example of something to reach for, but it’s a deep past.