Jerry A. Coyne in Quillette:

These days you can dismiss anything you don’t like by calling it “a religion.” Science, for instance, has been deemed essentially religious, despite the huge difference between a method of finding truth based on empirical verification and one based on unevidenced faith, revelation, authority, and scripture. Atheism, the direct opposite of religion, has also been characterized in this way, though believers who criticize secular worldviews as religious seem unaware of the irony of implying, “See—you’re just as bad as we are!” Even environmentalism has been described as a religion.

These days you can dismiss anything you don’t like by calling it “a religion.” Science, for instance, has been deemed essentially religious, despite the huge difference between a method of finding truth based on empirical verification and one based on unevidenced faith, revelation, authority, and scripture. Atheism, the direct opposite of religion, has also been characterized in this way, though believers who criticize secular worldviews as religious seem unaware of the irony of implying, “See—you’re just as bad as we are!” Even environmentalism has been described as a religion.

The latest false analogy between religious and nonreligious belief systems is John Staddon’s essay “Is Secular Humanism a Religion?” for Quillette. Staddon’s answer is “Yes,” but his reasoning is bizarre. One would think that it should be “Clearly not” for, after all, “secular” means “not religious,” and secular humanism is an areligious philosophy whose goal is to advance human welfare and morality without invoking gods or the supernatural.

Nevertheless, Staddon makes an oddly tendentious argument for the religious character of secular humanism.

More here.

How should we make sense of the Easter Sunday church and hotel

How should we make sense of the Easter Sunday church and hotel

After the shock and tears, the feelings of personal loss and collective grief, as well as after the dutiful if hagiographic journalism, one is left wondering how Carolee Schneemann’s life’s work is likely to be seen over time. There are many things I could say, but two things above all else occur to me to suggest here as ways forward.

After the shock and tears, the feelings of personal loss and collective grief, as well as after the dutiful if hagiographic journalism, one is left wondering how Carolee Schneemann’s life’s work is likely to be seen over time. There are many things I could say, but two things above all else occur to me to suggest here as ways forward. We’re often told that today’s North American critics are missing something vital. But what? Ever self-reliant, American critics often identify the missing element as a certain intensity, as though the questing knight has grown flabby and a little domestic. In American Audacity: In defense of literary daring, an impressive new collection of essays, the Boston-based critic and novelist William Giraldi sounds the alarm. “The danger is real now”, he writes, “godlike and unprecedented, all- powerful and everywhere. The Internet has zapped us all into obliging zombies; it makes yesterday’s threat from television look whimsical and rather cute.” Against these stupefying forces, Giraldi calls for the critic to return to fundamentals. “The critic’s chief loyalty is to the duet of beauty and wisdom”, he writes, “to the well-made and usefully wise, and to the ligatures between style and meaning.” Giraldi is the sort of critic – often the most helpful when one is choosing what to read – who insists on the paramount importance of a work’s aesthetic features. He is hostile to those who would perceive literature through a political or theoretical lens. “Ideology is the enemy of art because ideology is the end of imagination”, he avers.

We’re often told that today’s North American critics are missing something vital. But what? Ever self-reliant, American critics often identify the missing element as a certain intensity, as though the questing knight has grown flabby and a little domestic. In American Audacity: In defense of literary daring, an impressive new collection of essays, the Boston-based critic and novelist William Giraldi sounds the alarm. “The danger is real now”, he writes, “godlike and unprecedented, all- powerful and everywhere. The Internet has zapped us all into obliging zombies; it makes yesterday’s threat from television look whimsical and rather cute.” Against these stupefying forces, Giraldi calls for the critic to return to fundamentals. “The critic’s chief loyalty is to the duet of beauty and wisdom”, he writes, “to the well-made and usefully wise, and to the ligatures between style and meaning.” Giraldi is the sort of critic – often the most helpful when one is choosing what to read – who insists on the paramount importance of a work’s aesthetic features. He is hostile to those who would perceive literature through a political or theoretical lens. “Ideology is the enemy of art because ideology is the end of imagination”, he avers. We know a little of what the social novel was. At the very least, we know of Charles Dickens and what the literary historian Louis Cazamian calls that author’s “philosophy of Christmas.” I hope you will laugh a little here, as I think Cazamian is attempting to be at once ironic and precise. Dickens was arguably the first author to bring the urban lower middle class into the European novel as more than scenic decor; reflecting in various ways on his father’s time in debtor’s prison as well as his own stint as a factory laborer during that parent’s absence, Dickens described the precariousness produced by industrialization in generally moving detail—even if Americans are more apt to remember the amusing eccentricities of Tiny Tim and Miss Havisham than the sociological achievement of a work like 1854’s Hard Times, which stands as a sort of anatomy of the imaginary mill town of Coketown. Changes in the British political system and economy during the earlier part of the nineteenth century (expanded suffrage after 1832 and increasing readership of the press) meant that there was an eager audience for fiction that touched upon the organization of society. In the early 1830s, Harriet Martineau, a young, unmarried woman, became the author of a series of bestselling serial parables that explained basic economic concepts such as free trade, via “The Loom and the Lugger,” and unions, via “A Manchester Strike.” Martineau’s Illustrations of Political Economy (1832–34) emerged out of her conviction that the economic and the personal were not separate spheres, and her more than slightly didactic bent was surely influential for the style of serialized novel Dickens would first produce in 1836 with the Pickwick Papers. Dickens’s work built on Romanticism’s convictions regarding the importance of national history to contemporary identity, with the difference that the influence of modern (i.e., mechanized) systems on the individual were explored. In addition, unlike Sir Walter Scott, he of the sweeping national-historical romance, Dickens dealt unabashedly in coincidence, cuteness, and sentimentality—apparently hoping to motivate readers to philanthropic attitudes and works through minor styles of depiction designed to inspire pity.

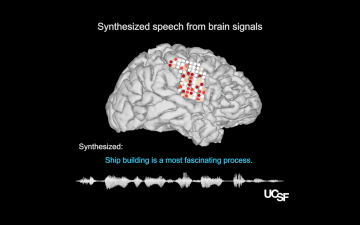

We know a little of what the social novel was. At the very least, we know of Charles Dickens and what the literary historian Louis Cazamian calls that author’s “philosophy of Christmas.” I hope you will laugh a little here, as I think Cazamian is attempting to be at once ironic and precise. Dickens was arguably the first author to bring the urban lower middle class into the European novel as more than scenic decor; reflecting in various ways on his father’s time in debtor’s prison as well as his own stint as a factory laborer during that parent’s absence, Dickens described the precariousness produced by industrialization in generally moving detail—even if Americans are more apt to remember the amusing eccentricities of Tiny Tim and Miss Havisham than the sociological achievement of a work like 1854’s Hard Times, which stands as a sort of anatomy of the imaginary mill town of Coketown. Changes in the British political system and economy during the earlier part of the nineteenth century (expanded suffrage after 1832 and increasing readership of the press) meant that there was an eager audience for fiction that touched upon the organization of society. In the early 1830s, Harriet Martineau, a young, unmarried woman, became the author of a series of bestselling serial parables that explained basic economic concepts such as free trade, via “The Loom and the Lugger,” and unions, via “A Manchester Strike.” Martineau’s Illustrations of Political Economy (1832–34) emerged out of her conviction that the economic and the personal were not separate spheres, and her more than slightly didactic bent was surely influential for the style of serialized novel Dickens would first produce in 1836 with the Pickwick Papers. Dickens’s work built on Romanticism’s convictions regarding the importance of national history to contemporary identity, with the difference that the influence of modern (i.e., mechanized) systems on the individual were explored. In addition, unlike Sir Walter Scott, he of the sweeping national-historical romance, Dickens dealt unabashedly in coincidence, cuteness, and sentimentality—apparently hoping to motivate readers to philanthropic attitudes and works through minor styles of depiction designed to inspire pity. Stroke, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and other medical conditions can rob people of their ability to speak. Their communication is limited to the speed at which they can move a cursor with their eyes (just eight to 10 words per minute), in contrast with the natural spoken pace of 120 to 150 words per minute. Now, although still a long way from restoring natural speech, researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, have generated intelligible sentences from the thoughts of people without speech difficulties.

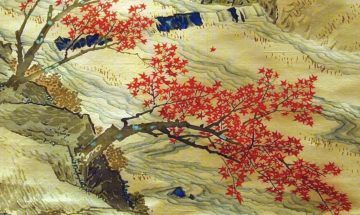

Stroke, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and other medical conditions can rob people of their ability to speak. Their communication is limited to the speed at which they can move a cursor with their eyes (just eight to 10 words per minute), in contrast with the natural spoken pace of 120 to 150 words per minute. Now, although still a long way from restoring natural speech, researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, have generated intelligible sentences from the thoughts of people without speech difficulties. I long to be in Japan in the autumn. For much of the year, my job, reporting on foreign conflicts and globalism on a human scale, forces me out onto the road; and with my mother in her eighties, living alone in the hills of California, I need to be there much of the time, too. But I try each year to be back in Japan for the season of fire and farewells. Cherry blossoms, pretty and frothy as schoolgirls’ giggles, are the face the country likes to present to the world, all pink and white eroticism; but it’s the reddening of the maple leaves under a blaze of ceramic-blue skies that is the place’s secret heart.

I long to be in Japan in the autumn. For much of the year, my job, reporting on foreign conflicts and globalism on a human scale, forces me out onto the road; and with my mother in her eighties, living alone in the hills of California, I need to be there much of the time, too. But I try each year to be back in Japan for the season of fire and farewells. Cherry blossoms, pretty and frothy as schoolgirls’ giggles, are the face the country likes to present to the world, all pink and white eroticism; but it’s the reddening of the maple leaves under a blaze of ceramic-blue skies that is the place’s secret heart. I was enthralled by Dennett and Chalmers’ recent discussion of the threats and prospects regarding artificial superintelligences. Dennett thinks we should protect ourselves by doing all we can to keep powerful AIs operating at the level of suggestion-making tools, while Chalmers is impressed by the market forces that will probably push us into devolving more and more responsibility to these opaque and alien minds. But I felt as if their picture of the space of possible AI minds could be usefully refined, and with that in mind I’d like to push on two further dimensions.

I was enthralled by Dennett and Chalmers’ recent discussion of the threats and prospects regarding artificial superintelligences. Dennett thinks we should protect ourselves by doing all we can to keep powerful AIs operating at the level of suggestion-making tools, while Chalmers is impressed by the market forces that will probably push us into devolving more and more responsibility to these opaque and alien minds. But I felt as if their picture of the space of possible AI minds could be usefully refined, and with that in mind I’d like to push on two further dimensions. I vividly remember the rush I felt after my first encounter with the

I vividly remember the rush I felt after my first encounter with the  There are, I think, three particularly striking things about Hark. First, it is not in the fanatical first-person. It features a multitude of centers of narrative consciousness, and this makes for a story that feels more spacious—less claustrophobically compulsive—than many of Lipsyte’s others. Second, and in direct relation to this, there is a spaciousness in the novel’s regard for what we might call its characters’ practices of belief. Hark himself, for instance, remains something of a well-drawn cipher in the book, a vivid blur, and in Lipsyte’s novel-wide willingness to demure from mercilessness, to withhold satirical fire and thus preserve some unvoided space of mystery about him—this unfunny man who professedly neither gets nor traffics in irony—we can feel a deliberate and, to my mind, telling recalibration of the novelist’s own marrow-deep impulses toward mockery. Page after page, and often through the lens of the hapless Fraz, the most familiar of Lipstye’s quasi-despairing middle-aged men, the novel turns over a new and startling question: What if a killing and all-devouring irony isn’t the way to survive the world?

There are, I think, three particularly striking things about Hark. First, it is not in the fanatical first-person. It features a multitude of centers of narrative consciousness, and this makes for a story that feels more spacious—less claustrophobically compulsive—than many of Lipsyte’s others. Second, and in direct relation to this, there is a spaciousness in the novel’s regard for what we might call its characters’ practices of belief. Hark himself, for instance, remains something of a well-drawn cipher in the book, a vivid blur, and in Lipsyte’s novel-wide willingness to demure from mercilessness, to withhold satirical fire and thus preserve some unvoided space of mystery about him—this unfunny man who professedly neither gets nor traffics in irony—we can feel a deliberate and, to my mind, telling recalibration of the novelist’s own marrow-deep impulses toward mockery. Page after page, and often through the lens of the hapless Fraz, the most familiar of Lipstye’s quasi-despairing middle-aged men, the novel turns over a new and startling question: What if a killing and all-devouring irony isn’t the way to survive the world? “To give the mundane its beautiful due” is how Updike described his own literary program, and in Carver the mundane is honed to ominous implication. You don’t often see Carver’s name hitched to Whitman’s, but consider the Whitmanian exuberance of the everyday: almost nothing is too insignificant to escape Whitman’s communion. Carver’s socially insignificant people, and the insignificant artifacts of their lives, are not insignificant to him. Wholly unlike Whitman, though, Carver’s literary program takes no stock of the sublime. His language achieves a demotic splendor, a conversational artfulness—always a grand talker, Carver wrote stories in an eminently spoken register; his art is as oral as Whitman’s—but his language cannot connect with that junction where this world rubs against the other. Though Carver’s characters often pine for exalted things, they cannot articulate their pining. The oppressive immediacy of their lives prevents such articulation. Transcendence is a privilege Carver’s people have perhaps heard rumor of but have not been granted access to.

“To give the mundane its beautiful due” is how Updike described his own literary program, and in Carver the mundane is honed to ominous implication. You don’t often see Carver’s name hitched to Whitman’s, but consider the Whitmanian exuberance of the everyday: almost nothing is too insignificant to escape Whitman’s communion. Carver’s socially insignificant people, and the insignificant artifacts of their lives, are not insignificant to him. Wholly unlike Whitman, though, Carver’s literary program takes no stock of the sublime. His language achieves a demotic splendor, a conversational artfulness—always a grand talker, Carver wrote stories in an eminently spoken register; his art is as oral as Whitman’s—but his language cannot connect with that junction where this world rubs against the other. Though Carver’s characters often pine for exalted things, they cannot articulate their pining. The oppressive immediacy of their lives prevents such articulation. Transcendence is a privilege Carver’s people have perhaps heard rumor of but have not been granted access to. The 18th century can seem like a boys’ club at the best of times, so writing a book about an actual all-male club requires delicate handling if it’s to offer something other than the usual narrative. Damrosch’s approach is to show that what makes the Club’s members worth revisiting is the fact that they weren’t always the ‘great men’ we picture them as being. In several cases they were dogged by anxieties or neuroses; often their cultivation of the intellect went hand in hand with an indulgence of powerful physical appetites.

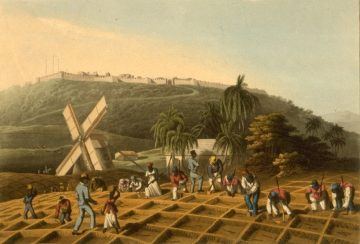

The 18th century can seem like a boys’ club at the best of times, so writing a book about an actual all-male club requires delicate handling if it’s to offer something other than the usual narrative. Damrosch’s approach is to show that what makes the Club’s members worth revisiting is the fact that they weren’t always the ‘great men’ we picture them as being. In several cases they were dogged by anxieties or neuroses; often their cultivation of the intellect went hand in hand with an indulgence of powerful physical appetites. Elizabeth Cady Stanton started her activism as an ardent abolitionist. When the 1840

Elizabeth Cady Stanton started her activism as an ardent abolitionist. When the 1840  You are what you eat. And when you eat a lot of dirt, the makeup of your gut will change—at least, if you’re a baboon. A new study shows local soils, not genetics, may be the primary determinant of baboons’ gut microbiota, the vast ecosystem of microorganisms that live in the gut, digesting food, fighting infections, and breaking down toxins. Past research has shown that the gut microbiota of baboons varies across different populations. Scientists wanted to know the cause: Is it the genes they share with other relatives, the distance between populations, or the environment that creates these internal changes? To find out, the researchers gathered poop from 14 different baboon populations in Kenya’s primate hybrid zone—an area where yellow baboons (Papio cynocephalus) and anubis baboons (P. anubis) mingle and interbreed (above). Along with analyzing the baboons’ DNA, researchers looked at 13 different characteristics of the environment where the stool was collected, including vegetation, elevation, climate, and soil.

You are what you eat. And when you eat a lot of dirt, the makeup of your gut will change—at least, if you’re a baboon. A new study shows local soils, not genetics, may be the primary determinant of baboons’ gut microbiota, the vast ecosystem of microorganisms that live in the gut, digesting food, fighting infections, and breaking down toxins. Past research has shown that the gut microbiota of baboons varies across different populations. Scientists wanted to know the cause: Is it the genes they share with other relatives, the distance between populations, or the environment that creates these internal changes? To find out, the researchers gathered poop from 14 different baboon populations in Kenya’s primate hybrid zone—an area where yellow baboons (Papio cynocephalus) and anubis baboons (P. anubis) mingle and interbreed (above). Along with analyzing the baboons’ DNA, researchers looked at 13 different characteristics of the environment where the stool was collected, including vegetation, elevation, climate, and soil. CAN POEMS TEACH US how to live? What does it mean to approach poetry as a source of self-help? It’s not hard to call to mind examples of poetry that rouse or soothe or refocus a reader, lifting or quieting the mind like a deep breath. Yet much of the poetry encountered in literature classrooms and canonical anthologies may not readily reflect the self that is reading it, and therefore may not readily become a tool of self-improvement. The work of many modernist poets in particular is placed under the banner of “art for art’s sake,” a motto meant to explicitly free such poetry from the responsibility of serving a didactic or utilitarian function. The poems of Wallace Stevens, for instance, are frequently taken to epitomize the kind of high modernist difficulty that in its slippery symbology and ambiguous affect would seemingly resist being reliably employed for any useful purpose.

CAN POEMS TEACH US how to live? What does it mean to approach poetry as a source of self-help? It’s not hard to call to mind examples of poetry that rouse or soothe or refocus a reader, lifting or quieting the mind like a deep breath. Yet much of the poetry encountered in literature classrooms and canonical anthologies may not readily reflect the self that is reading it, and therefore may not readily become a tool of self-improvement. The work of many modernist poets in particular is placed under the banner of “art for art’s sake,” a motto meant to explicitly free such poetry from the responsibility of serving a didactic or utilitarian function. The poems of Wallace Stevens, for instance, are frequently taken to epitomize the kind of high modernist difficulty that in its slippery symbology and ambiguous affect would seemingly resist being reliably employed for any useful purpose.