Alicia Ault in Smithsonian:

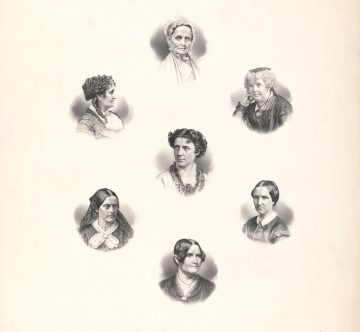

Elizabeth Cady Stanton started her activism as an ardent abolitionist. When the 1840 World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London devolved into a heated debate about whether or not women should be allowed to participate, Stanton lost some faith in the movement. It was there that she met Lucretia Mott, a longtime women’s activist, and the two bonded. Upon their return to the United States, they were determined to convene a women’s assembly of their own. It took until 1848 for that meeting, held in Seneca Falls, New York, to come together with a few hundred attendees, including Frederick Douglass. Douglass was pivotal in getting Stanton and Mott’s 12-item Declaration of Sentiments approved by the conventioneers.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton started her activism as an ardent abolitionist. When the 1840 World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London devolved into a heated debate about whether or not women should be allowed to participate, Stanton lost some faith in the movement. It was there that she met Lucretia Mott, a longtime women’s activist, and the two bonded. Upon their return to the United States, they were determined to convene a women’s assembly of their own. It took until 1848 for that meeting, held in Seneca Falls, New York, to come together with a few hundred attendees, including Frederick Douglass. Douglass was pivotal in getting Stanton and Mott’s 12-item Declaration of Sentiments approved by the conventioneers.

Three years later, Stanton recruited a Rochester, New York, resident, Susan B. Anthony, who had been advocating for temperance and abolition, to what was then primarily a women’s rights cause. Over the next two decades, the demands for women’s rights and the rights of free men and women of color, and then, post-Civil War, of former slaves, competed for primacy. Stanton and Anthony were on the verge of being cast out of the suffragist movement, in part, because of their alliance with the radical divorcée Victoria Woodhull, the first woman to run for president, in 1872. Woodhull was a flamboyant character, elegantly captured in a portrait by the famed photographer Mathew Brady. But it was Woodhull’s advocacy of “free love”—and her public allegation that one of the abolitionist movement’s leaders, Henry Ward Beecher, was having an affair—that made her kryptonite for the suffragists, including Stanton and Anthony.

More here.