Kerry Grens in The Scientist:

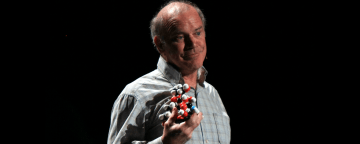

Kary Mullis, whose invention of the polymerase chain reaction technique earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993, died of pneumonia on August 7, according to MyNewsLA.com. He was 74 years old. According to a 1998 profile in The Washington Post, Mullis was known as a “weird” figure in science and “flamboyant” philanderer who evangelized the use of LSD, denied the evidence for both global warming and HIV as a cause of AIDS, consulted for O.J. Simpson’s legal defense, and formed a company that sold jewelry embedded with celebrities’ DNA. The opening paragraph of his Nobel autobiography includes a scene depicting a visit from Mullis’s dying grandfather in “non-substantial form.” “He was personally and professionally one of the more iconic personalities science has ever witnessed,” Rich Robbins, the founder and CEO of Wareham Development, a real estate developer for a number of biotech companies, tells the Emeryville, California-based paper, the E’ville Eye.

Kary Mullis, whose invention of the polymerase chain reaction technique earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993, died of pneumonia on August 7, according to MyNewsLA.com. He was 74 years old. According to a 1998 profile in The Washington Post, Mullis was known as a “weird” figure in science and “flamboyant” philanderer who evangelized the use of LSD, denied the evidence for both global warming and HIV as a cause of AIDS, consulted for O.J. Simpson’s legal defense, and formed a company that sold jewelry embedded with celebrities’ DNA. The opening paragraph of his Nobel autobiography includes a scene depicting a visit from Mullis’s dying grandfather in “non-substantial form.” “He was personally and professionally one of the more iconic personalities science has ever witnessed,” Rich Robbins, the founder and CEO of Wareham Development, a real estate developer for a number of biotech companies, tells the Emeryville, California-based paper, the E’ville Eye.

Mullis was born in North Carolina in 1944 and earned a chemistry degree from Georgia Tech and a PhD in biochemistry from the University of California, Berkeley. In the early 1980s, when Mullis was working for the biotech company Cetus Corp in Emeryville, he developed the DNA replication technique polymerase chain reaction (PCR)—one of the most widely used methods in molecular biology. Writing in The Scientist in 2003, Mullis described his first attempt at PCR in 1983 as “a long-shot experiment. . . . so [at midnight] I poured myself a cold Becks into a prechilled 500 ml beaker from the isotope freezer for luck, and went home. I ran a gel the next afternoon [and] stained it with ethidium. It took several months to arrive at conditions [that] would produce a convincing result.” Both Science and Nature rejected the resulting manuscript, which was ultimately published in Methods in Enzymology in 1987.

More here.

Climate scientists’ worst-case scenarios back in 2007, the first year the Northwest Passage became navigable without an icebreaker (today, you can book a cruise through it), have all been overtaken by the unforeseen acceleration of events. No one imagined that twelve years later the United Nations would report that we have just twelve years left to avert global catastrophe, which would involve cutting fossil-fuel use nearly by half. Since 2007, the UN now says, we’ve done everything wrong. New coal plants built since the 2015 Paris climate agreement have already doubled the equivalent coal-energy output of Russia and Japan, and 260 more are underway.

Climate scientists’ worst-case scenarios back in 2007, the first year the Northwest Passage became navigable without an icebreaker (today, you can book a cruise through it), have all been overtaken by the unforeseen acceleration of events. No one imagined that twelve years later the United Nations would report that we have just twelve years left to avert global catastrophe, which would involve cutting fossil-fuel use nearly by half. Since 2007, the UN now says, we’ve done everything wrong. New coal plants built since the 2015 Paris climate agreement have already doubled the equivalent coal-energy output of Russia and Japan, and 260 more are underway. The recent revolutions in Algeria and Sudan remind us that bottom-up movements of people power can create sweeping political transformations. They did this in part by mobilizing huge numbers of active protestors—

The recent revolutions in Algeria and Sudan remind us that bottom-up movements of people power can create sweeping political transformations. They did this in part by mobilizing huge numbers of active protestors— The Hindu-supremacist government of

The Hindu-supremacist government of  Writers have their pet themes, favorite words, stubborn obsessions. But their signature, the essence of their style, is felt someplace deeper — at the level of pulse. Style is first felt in rhythm and cadence, from how sentences build and bend, sag or snap. Style, I’d argue, is 90 percent punctuation.

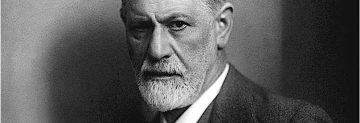

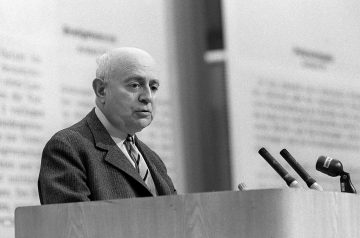

Writers have their pet themes, favorite words, stubborn obsessions. But their signature, the essence of their style, is felt someplace deeper — at the level of pulse. Style is first felt in rhythm and cadence, from how sentences build and bend, sag or snap. Style, I’d argue, is 90 percent punctuation. One of the explanations for the rise of populist nationalist myths today goes back to the complicated dynamics between the individual and society, and between reason and fantasy. The thinker who might help us understand our current political storms is no other than Sigmund Freud. Freud is best known for his more controversial theories on sexuality. But we need not buy Freudian mechanics or his clinical theories. Enough of value remains without Oedipus. Freudian theory explores the tension between unconscious desires and the controlling ego, whose rational faculties, while fallible, may be marshalled to scrutinise our emotional drives. On this account, the freedom that humans possess rests solely in recognising and controlling fantasies and the passions that accompany them. With such awareness we are, at least, in a better position to judge and direct our actions – mitigating those that are destructive and strengthening the beneficial. This isn’t a new idea for western philosophy, and it goes at least as far back as Plato and Aristotle.

One of the explanations for the rise of populist nationalist myths today goes back to the complicated dynamics between the individual and society, and between reason and fantasy. The thinker who might help us understand our current political storms is no other than Sigmund Freud. Freud is best known for his more controversial theories on sexuality. But we need not buy Freudian mechanics or his clinical theories. Enough of value remains without Oedipus. Freudian theory explores the tension between unconscious desires and the controlling ego, whose rational faculties, while fallible, may be marshalled to scrutinise our emotional drives. On this account, the freedom that humans possess rests solely in recognising and controlling fantasies and the passions that accompany them. With such awareness we are, at least, in a better position to judge and direct our actions – mitigating those that are destructive and strengthening the beneficial. This isn’t a new idea for western philosophy, and it goes at least as far back as Plato and Aristotle. In Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer, Richard Holmes described how, aged 18, he followed the route taken by Robert Louis Stevenson and his donkey almost 100 years earlier as they walked through the Massif Central in France. Sleeping, as Stevenson did, beneath the stars, bathing in rivers, and feeling half mad on the excess of liberty, Holmes learned that his vocation was to live like a ghost crab in another man’s shell. No one has described better the strange and obsessive nature of biographical pursuit, and the business of “footstepping” has since become associated with the Holmesian style of method-biography, in which the biographical subject returns from the dead with a palpable physical presence.

In Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer, Richard Holmes described how, aged 18, he followed the route taken by Robert Louis Stevenson and his donkey almost 100 years earlier as they walked through the Massif Central in France. Sleeping, as Stevenson did, beneath the stars, bathing in rivers, and feeling half mad on the excess of liberty, Holmes learned that his vocation was to live like a ghost crab in another man’s shell. No one has described better the strange and obsessive nature of biographical pursuit, and the business of “footstepping” has since become associated with the Holmesian style of method-biography, in which the biographical subject returns from the dead with a palpable physical presence.

Marshall Sahlins in Counterpunch:

Marshall Sahlins in Counterpunch: The late Anges Heller in Public Seminar:

The late Anges Heller in Public Seminar: Joy James in Boston Review:

Joy James in Boston Review: Andreas Huyssen in n+1:

Andreas Huyssen in n+1:

However, it was an invention seven years earlier that restructured not just how language appears, but indeed the very rhythm of sentences; for, in 1496, Manutius introduced a novel bit of punctuation, a jaunty little man with leg splayed to the left as if he was pausing to hold open a door for the reader before they entered the next room, the odd mark at the caesura of this byzantine sentence that is known to posterity as the semicolon. Punctuation exists not in the wild; it is not a function of how we hear the word, but rather of how we write the Word. What the theorist Walter Ong described in his classic

However, it was an invention seven years earlier that restructured not just how language appears, but indeed the very rhythm of sentences; for, in 1496, Manutius introduced a novel bit of punctuation, a jaunty little man with leg splayed to the left as if he was pausing to hold open a door for the reader before they entered the next room, the odd mark at the caesura of this byzantine sentence that is known to posterity as the semicolon. Punctuation exists not in the wild; it is not a function of how we hear the word, but rather of how we write the Word. What the theorist Walter Ong described in his classic  Some claim that the idea of human freedom is built on illusions about human specialness that are a holdover from a religious conception of the world, and that they should be swept aside with the advancing tides of science. This position has been trumpeted loudly by people who present themselves as brave defenders of science: by scientists such as Einstein, Stephen Hawking and Richard Dawkins, and by philosophers including Alexander Rosenberg and Sam Harris. To most people, however, it seems literally unbelievable that the scales of fate don’t hang in the balance when making a difficult decision. And it is not just those dark nights of the soul where this matters. You think that you could cross the street here or there, pick these socks or those, go to bed at a reasonable hour or stay up, howl at the moon and eat donuts till dawn. Every choice is a juncture in history and it is up to you to determine which way to go.

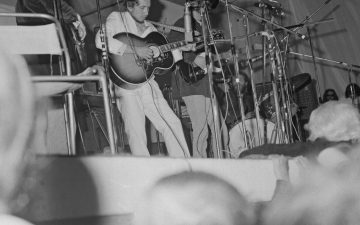

Some claim that the idea of human freedom is built on illusions about human specialness that are a holdover from a religious conception of the world, and that they should be swept aside with the advancing tides of science. This position has been trumpeted loudly by people who present themselves as brave defenders of science: by scientists such as Einstein, Stephen Hawking and Richard Dawkins, and by philosophers including Alexander Rosenberg and Sam Harris. To most people, however, it seems literally unbelievable that the scales of fate don’t hang in the balance when making a difficult decision. And it is not just those dark nights of the soul where this matters. You think that you could cross the street here or there, pick these socks or those, go to bed at a reasonable hour or stay up, howl at the moon and eat donuts till dawn. Every choice is a juncture in history and it is up to you to determine which way to go. Fifty years ago this month, Bob Dylan played the Isle of Wight Festival. They say if you can remember 1969 you weren’t there, but I do and I was, boomerphobes. I can even tell you what half a century feels like if you’re interested, although it’s a bit layered. A bit contradictory.

Fifty years ago this month, Bob Dylan played the Isle of Wight Festival. They say if you can remember 1969 you weren’t there, but I do and I was, boomerphobes. I can even tell you what half a century feels like if you’re interested, although it’s a bit layered. A bit contradictory. It’s hard to overstate the significance of

It’s hard to overstate the significance of