Alex Preston in The Guardian:

Ramallah, in the heart of the West Bank, is only a few miles north of Jerusalem, its nose pressed up against the dashes of Palestine’s borders on the maps, official markers of the city’s – and the country’s – provisional nature. It is a place of scarcely 30,000 inhabitants, historically a Christian city (although now the majority are Muslim) and also one of cold winters and carefully tended gardens, chosen by the PLO as its de facto headquarters following the Oslo accords of 1993 and 1995. It is, above all, a city of authors, home to Palestine’s greatest poet, the late Mahmoud Darwish, and the man we can now recognise as its greatest prose writer, Raja Shehadeh.

Ramallah, in the heart of the West Bank, is only a few miles north of Jerusalem, its nose pressed up against the dashes of Palestine’s borders on the maps, official markers of the city’s – and the country’s – provisional nature. It is a place of scarcely 30,000 inhabitants, historically a Christian city (although now the majority are Muslim) and also one of cold winters and carefully tended gardens, chosen by the PLO as its de facto headquarters following the Oslo accords of 1993 and 1995. It is, above all, a city of authors, home to Palestine’s greatest poet, the late Mahmoud Darwish, and the man we can now recognise as its greatest prose writer, Raja Shehadeh.

Shehadeh won the Orwell prize for his 2007 book Palestinian Walks and published a powerful memoir of a cross-border friendship, Where the Line Is Drawn, in 2017. These books built on earlier memoirs, Strangers in the Houseand When the Bulbul Stopped Singing, written at the beginning of the century, during the second intifada, when any optimism that the Oslo agreements might bring peace had died, and a new kind of hope gripped Palestine – that desperate and violent resistance might succeed where political negotiation had failed.

Palestinian Walks was the story of 27 years’ worth of walking in the hills of the West Bank, while Going Hometakes place on a single day, 5 June 2017, the 50th anniversary of the Israeli invasion of Palestine. Shehadeh sets out to walk to a meeting at his office – he’s a practicing lawyer as well as the founder of Al-Haq, the human rights campaign group – and strolls through the city in which he has spent most of his life. Normally, the walk to his office takes only 45 minutes, but he stretches it out to four hours, chewing over the history of his city. After the meeting, he walks home, reflecting on “how the city I grew up in has remained with me”. Going Home is a travelogue, a lament, a record of a vanishing city and its near-vanished inhabitants, most of whom (despite World Bank incentives) have fled to the US or Europe.

More here.

TSAKANE, South Africa — When she joined a trial of new tuberculosis drugs, the dying young woman weighed just 57 pounds. Stricken with a deadly strain of the disease, she was mortally terrified. Local nurses told her the Johannesburg hospital to which she must be transferred was very far away — and infested with vervet monkeys. “I cried the whole way in the ambulance,” Tsholofelo Msimango recalled recently. “They said I would live with monkeys and the sisters there were not nice and the food was bad and there was no way I would come back. They told my parents to fix the insurance because I would die.” Five years later, Ms. Msimango, 25, is now tuberculosis-free. She is healthy at 103 pounds, and has a young son. The trial she joined was small — it enrolled only 109 patients — but experts are calling the preliminary results groundbreaking. The drug regimen tested on Ms. Msimango has shown a 90 percent success rate against a deadly plague, extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis.

TSAKANE, South Africa — When she joined a trial of new tuberculosis drugs, the dying young woman weighed just 57 pounds. Stricken with a deadly strain of the disease, she was mortally terrified. Local nurses told her the Johannesburg hospital to which she must be transferred was very far away — and infested with vervet monkeys. “I cried the whole way in the ambulance,” Tsholofelo Msimango recalled recently. “They said I would live with monkeys and the sisters there were not nice and the food was bad and there was no way I would come back. They told my parents to fix the insurance because I would die.” Five years later, Ms. Msimango, 25, is now tuberculosis-free. She is healthy at 103 pounds, and has a young son. The trial she joined was small — it enrolled only 109 patients — but experts are calling the preliminary results groundbreaking. The drug regimen tested on Ms. Msimango has shown a 90 percent success rate against a deadly plague, extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis.

Adam Shatz in The New Yorker:

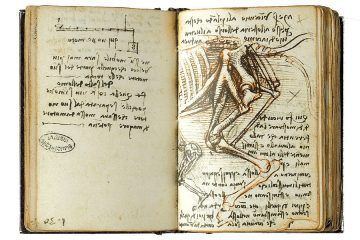

Adam Shatz in The New Yorker: As someone who appreciates Leonardo da Vinci’s painting skills, I’ve long marveled at how crowds rush past his most sublime painting, “The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne,” to line up in front of the “Mona Lisa” at the Louvre Museum in Paris. The art critic in me wants to say, “Wait! Look at this one. See the poses of entwining bodies and gazes, the melting regard of the mother for her child, the translucent folds of cloth, the baby’s chubby legs.” It’s a perfect combination of humanity and divinity. Now, at the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death, scholars, art lovers, and the public are taking a far-reaching look at his career. Exhibitions in Italy and England, as well as the largest-ever survey of his work that opens at the Louvre this fall, are celebrating the master’s achievements not only in art but also in science.

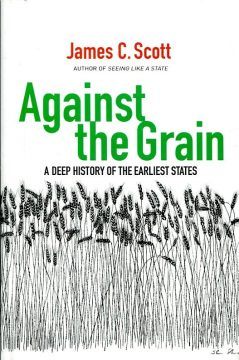

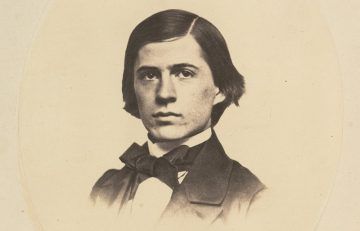

As someone who appreciates Leonardo da Vinci’s painting skills, I’ve long marveled at how crowds rush past his most sublime painting, “The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne,” to line up in front of the “Mona Lisa” at the Louvre Museum in Paris. The art critic in me wants to say, “Wait! Look at this one. See the poses of entwining bodies and gazes, the melting regard of the mother for her child, the translucent folds of cloth, the baby’s chubby legs.” It’s a perfect combination of humanity and divinity. Now, at the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death, scholars, art lovers, and the public are taking a far-reaching look at his career. Exhibitions in Italy and England, as well as the largest-ever survey of his work that opens at the Louvre this fall, are celebrating the master’s achievements not only in art but also in science. The roll of scientists born in the 19th century is as impressive as any century in history. Names such as Albert Einstein, Nikola Tesla, George Washington Carver, Alfred North Whitehead, Louis Agassiz, Benjamin Peirce, Leo Szilard, Edwin Hubble, Katharine Blodgett, Thomas Edison, Gerty Cori, Maria Mitchell, Annie Jump Cannon and Norbert Wiener created a legacy of knowledge and scientific method that fuels our modern lives. Which of these, though, was ‘the best’? Remarkably, in the brilliant light of these names, there was in fact a scientist who surpassed all others in sheer intellectual virtuosity. Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914), pronounced ‘purse’, was a solitary eccentric working in the town of Milford, Pennsylvania, isolated from any intellectual centre. Although many of his contemporaries shared the view that Peirce was a genius of historic proportions, he is little-known today. His current obscurity belies the prediction of the German mathematician Ernst Schröder, who said that Peirce’s ‘fame [will] shine like that of Leibniz or Aristotle into all the thousands of years to come’.

The roll of scientists born in the 19th century is as impressive as any century in history. Names such as Albert Einstein, Nikola Tesla, George Washington Carver, Alfred North Whitehead, Louis Agassiz, Benjamin Peirce, Leo Szilard, Edwin Hubble, Katharine Blodgett, Thomas Edison, Gerty Cori, Maria Mitchell, Annie Jump Cannon and Norbert Wiener created a legacy of knowledge and scientific method that fuels our modern lives. Which of these, though, was ‘the best’? Remarkably, in the brilliant light of these names, there was in fact a scientist who surpassed all others in sheer intellectual virtuosity. Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914), pronounced ‘purse’, was a solitary eccentric working in the town of Milford, Pennsylvania, isolated from any intellectual centre. Although many of his contemporaries shared the view that Peirce was a genius of historic proportions, he is little-known today. His current obscurity belies the prediction of the German mathematician Ernst Schröder, who said that Peirce’s ‘fame [will] shine like that of Leibniz or Aristotle into all the thousands of years to come’. Cassavetes felt galvanized by the looseness and freedom he (mis)read into jazz, which enabled him to make a film with little knowledge or money. At the very least, he shared one quality with Mingus — an ability to bully the people he worked with into doing what he wanted them to do. In a functional sense, both the radical filmmaker and the radical jazz composer were as domineering and rigid as the mainstream structures they railed against.

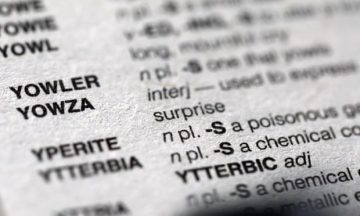

Cassavetes felt galvanized by the looseness and freedom he (mis)read into jazz, which enabled him to make a film with little knowledge or money. At the very least, he shared one quality with Mingus — an ability to bully the people he worked with into doing what he wanted them to do. In a functional sense, both the radical filmmaker and the radical jazz composer were as domineering and rigid as the mainstream structures they railed against. Each chapter explodes a common myth about language. Shariatmadari begins with the most common myth: that standards of English are declining. This is a centuries-old lament for which, he points out, there has never been any evidence. Older people buy into the myth because young people, who are more mobile and have wider social networks, are innovators in language as in other walks of life. Their habit of saying “aks” instead of “ask”, for instance, is a perfectly respectable example of metathesis, a natural linguistic process where the sounds in words swap round. (The word “wasp” used to be “waps” and “horse” used to be “hros”.) Youth is the driver of linguistic change. This means that older people feel linguistic alienation even as they control the institutions – universities, publishers, newspapers, broadcasters – that define standard English.

Each chapter explodes a common myth about language. Shariatmadari begins with the most common myth: that standards of English are declining. This is a centuries-old lament for which, he points out, there has never been any evidence. Older people buy into the myth because young people, who are more mobile and have wider social networks, are innovators in language as in other walks of life. Their habit of saying “aks” instead of “ask”, for instance, is a perfectly respectable example of metathesis, a natural linguistic process where the sounds in words swap round. (The word “wasp” used to be “waps” and “horse” used to be “hros”.) Youth is the driver of linguistic change. This means that older people feel linguistic alienation even as they control the institutions – universities, publishers, newspapers, broadcasters – that define standard English. Katia Moskvitch in Quanta:

Katia Moskvitch in Quanta: Thomas Meaney in The American Historical Review:

Thomas Meaney in The American Historical Review: Quinn Slobodian and William Callison in Dissent:

Quinn Slobodian and William Callison in Dissent: Nikole Hannah-Jones in the NYT:

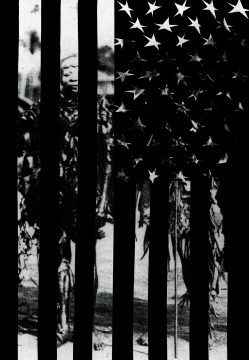

Nikole Hannah-Jones in the NYT: One of the occupational and intellectual hazards of being a historian is that current events often seem far less new to oneself than they do to others. Recently a leftish liberal friend told me that the United States under the Donald Trump had “become a lethal society.” My friend cited the neofascist Trump’s: horrible family separations and concentration camps on the border; openly white-nationalist assaults on four progressive nonwhite and female Congresswomen; real and threatened roundups of undocumented immigrants; fascist-style and hate-filled “Make America Great Again” rallies; encouragement of white supremacist terrorism; alliance with right-wing evangelical Christian fascists.

One of the occupational and intellectual hazards of being a historian is that current events often seem far less new to oneself than they do to others. Recently a leftish liberal friend told me that the United States under the Donald Trump had “become a lethal society.” My friend cited the neofascist Trump’s: horrible family separations and concentration camps on the border; openly white-nationalist assaults on four progressive nonwhite and female Congresswomen; real and threatened roundups of undocumented immigrants; fascist-style and hate-filled “Make America Great Again” rallies; encouragement of white supremacist terrorism; alliance with right-wing evangelical Christian fascists.