Olivia Laing in IAI News:

Loss is a cousin of loneliness. They intersect and overlap, and so it’s not surprising that a work of mourning might invoke a feeling of aloneness, of separation. Mortality is lonely. Physical existence is lonely by its nature, stuck in a body that’s moving inexorably towards decay, shrinking, wastage and fracture. Then there’s the loneliness of bereavement, the loneliness of lost or damaged love, of missing one or many specific people, the loneliness of mourning.

Loss is a cousin of loneliness. They intersect and overlap, and so it’s not surprising that a work of mourning might invoke a feeling of aloneness, of separation. Mortality is lonely. Physical existence is lonely by its nature, stuck in a body that’s moving inexorably towards decay, shrinking, wastage and fracture. Then there’s the loneliness of bereavement, the loneliness of lost or damaged love, of missing one or many specific people, the loneliness of mourning.

Loneliness as a desire for closeness, for joining up, joining in, joining together, for gathering what has otherwise been sundered, abandoned, broken or left in isolation. Loneliness as a longing for integration, for a sense of feeling whole. It’s a funny business, threading things together, patching them up with cotton or string. Practical, but also symbolic, a work of the hands and the psyche alike. One of the most thoughtful accounts of the meanings contained in activities of this kind is provided by the psychoanalyst and paediatrician D. W. Winnicott, an heir to the work of Melanie Klein. Winnicott began his psychoanalytic career treating evacuee children during the Second World War. He worked lifelong on attachment and separation, developing along the way the concept of the transitional object, of holding, and of false and real selves, and how they develop in response to environments of danger and of safety.

In Playing and Reality, he describes the case of a small boy whose mother repeatedly left him to go into hospital, first to have his baby sister and then to receive treatment for depression. In the wake of these experiences, the boy became obsessed with string, using it to tie the furniture in the house together, knotting tables to chairs, yoking cushions to the fireplace. On one alarming occasion, he even tied a string around the neck of his infant sister.

More here.

The word “science” typically evokes epistemic ambitions to explore the fundamental laws of the natural world. This is the stuff of philosophical reflection and documentary specials—and it is unquestionably important. This ethereal vision of science appears starkly divorced from the messy fray of “politics,” however you might want to understand the term.

The word “science” typically evokes epistemic ambitions to explore the fundamental laws of the natural world. This is the stuff of philosophical reflection and documentary specials—and it is unquestionably important. This ethereal vision of science appears starkly divorced from the messy fray of “politics,” however you might want to understand the term. In 1915, Albert Einstein wrote a letter to the philosopher and physicist Moritz Schlick, who had recently composed an article on the theory of relativity. Einstein praised it: ‘From the philosophical perspective, nothing nearly as clear seems to have been written on the topic.’ Then he went on to express his intellectual debt to ‘Hume, whose Treatise of Human Nature I had studied avidly and with admiration shortly before discovering the theory of relativity. It is very possible that without these philosophical studies I would not have arrived at the solution.’

In 1915, Albert Einstein wrote a letter to the philosopher and physicist Moritz Schlick, who had recently composed an article on the theory of relativity. Einstein praised it: ‘From the philosophical perspective, nothing nearly as clear seems to have been written on the topic.’ Then he went on to express his intellectual debt to ‘Hume, whose Treatise of Human Nature I had studied avidly and with admiration shortly before discovering the theory of relativity. It is very possible that without these philosophical studies I would not have arrived at the solution.’ Women in loose robes dragged toddlers, babies propped upon their hips. Men carrying parents and grandparents on their shoulders stepped ahead, calling back for assurances as women collapsed in the heat. Flimsy plastic bags, crammed with clothes and other belongings, dangled off shoulders and wrists. In the midday glaze, as light shimmered off the desert like water droplets, the scene at the Syrian-Iraqi border seemed almost biblical. My Iraqi colleague Ali, who had already tasted the wrath of displacement from his own country, squatted in the shade of our car and cried.

Women in loose robes dragged toddlers, babies propped upon their hips. Men carrying parents and grandparents on their shoulders stepped ahead, calling back for assurances as women collapsed in the heat. Flimsy plastic bags, crammed with clothes and other belongings, dangled off shoulders and wrists. In the midday glaze, as light shimmered off the desert like water droplets, the scene at the Syrian-Iraqi border seemed almost biblical. My Iraqi colleague Ali, who had already tasted the wrath of displacement from his own country, squatted in the shade of our car and cried. To put it mildly, Christianity has a complicated relationship with flesh. The same Paul who declared the Lord’s ownership of the body also bequeathed to subsequent Christian history a disdain for physicality through his—misunderstood, as most interpreters now think, but no less influential for being so—sharp contrast between the life of the flesh and the new life bestowed by and in the Spirit of Jesus. Stark affirmations such as the one he wrote to the Corinthians—“flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God”—at minimum lent confidence to later Christian denigrators of the body who imagined salvation as an escape from fleshly imprisonment and, at maximum, convinced generations of Christians that following Jesus ought to entail hating the body.

To put it mildly, Christianity has a complicated relationship with flesh. The same Paul who declared the Lord’s ownership of the body also bequeathed to subsequent Christian history a disdain for physicality through his—misunderstood, as most interpreters now think, but no less influential for being so—sharp contrast between the life of the flesh and the new life bestowed by and in the Spirit of Jesus. Stark affirmations such as the one he wrote to the Corinthians—“flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God”—at minimum lent confidence to later Christian denigrators of the body who imagined salvation as an escape from fleshly imprisonment and, at maximum, convinced generations of Christians that following Jesus ought to entail hating the body. For a brief moment,

For a brief moment,  The eminent art historian Michael Fried has set out, in his own energetic and independent style, to answer this question—what was literary impressionism?—and to do so unencumbered by the general principles that have so far cohered around the term in the work of literary critics and art historians. This may bother some readers who expect a more direct engagement with the critical history of the term. Fried’s approach is to start the inquiry afresh, using detailed readings of passages in individual works to derive his own answer to his title’s question. “If my specific readings and my overall argument cumulatively gain traction on their own terms,” he writes, “I shall consider this book a success.”

The eminent art historian Michael Fried has set out, in his own energetic and independent style, to answer this question—what was literary impressionism?—and to do so unencumbered by the general principles that have so far cohered around the term in the work of literary critics and art historians. This may bother some readers who expect a more direct engagement with the critical history of the term. Fried’s approach is to start the inquiry afresh, using detailed readings of passages in individual works to derive his own answer to his title’s question. “If my specific readings and my overall argument cumulatively gain traction on their own terms,” he writes, “I shall consider this book a success.” It consists of nothing more than an intermittent correspondence between two friends. Yet the epistolary form is deceptively efficient, supplying backstory, plot, character, dialogue and more than one narrative voice before a conventional novel might have cleared its throat. Within a page or two, we are in the world of Martin and Max, both German, the latter a Jew now living in San Francisco, the former now back in Munich – two men who have been business partners, friends and whose families have, as we shall discover, been intimately connected.

It consists of nothing more than an intermittent correspondence between two friends. Yet the epistolary form is deceptively efficient, supplying backstory, plot, character, dialogue and more than one narrative voice before a conventional novel might have cleared its throat. Within a page or two, we are in the world of Martin and Max, both German, the latter a Jew now living in San Francisco, the former now back in Munich – two men who have been business partners, friends and whose families have, as we shall discover, been intimately connected. Is there anything CRISPR can’t do? Scientists have wielded

Is there anything CRISPR can’t do? Scientists have wielded  A living room in Grantwood, N.J., has a good claim to being the birthplace, in the late 1920s and early 1930s, of a new science of humankind. Amid the demands of advising and fund-raising, the chair of the Columbia University anthropology department, Franz Boas, had decided to host regular Tuesday evening seminars at his suburban home. His students, passing plates of oatmeal cookies, were elaborating a way of seeing the world. They called it cultural relativity. Their essential finding was that societies did not come rank-ordered as civilized or primitive, moral or deviant. Each culture was only a sampling taken from the vast inventory of possible human beliefs and practices.

A living room in Grantwood, N.J., has a good claim to being the birthplace, in the late 1920s and early 1930s, of a new science of humankind. Amid the demands of advising and fund-raising, the chair of the Columbia University anthropology department, Franz Boas, had decided to host regular Tuesday evening seminars at his suburban home. His students, passing plates of oatmeal cookies, were elaborating a way of seeing the world. They called it cultural relativity. Their essential finding was that societies did not come rank-ordered as civilized or primitive, moral or deviant. Each culture was only a sampling taken from the vast inventory of possible human beliefs and practices. Just about everything we know that decreases the risk of developing cancer — exercise, healthful eating, not smoking, and the like — is associated with healthier tissues, which favor normal cell types.

Just about everything we know that decreases the risk of developing cancer — exercise, healthful eating, not smoking, and the like — is associated with healthier tissues, which favor normal cell types.

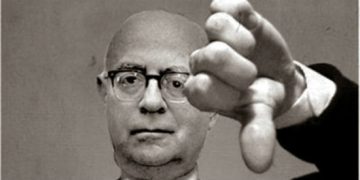

Academic, stuffy, German – Theodor W. Adorno has become emblematic of a certain sense of unfeeling in art. He was critical of TV, partial to Schoenberg, and aggrieved by the crassness of life in exile in 1940s America. Some of his students, infatuated with the youthful spontaneity of 1968, supposed that Adorno represented the old institutions that continued into post-war Europe, seeing his criticisms of mass culture being ‘pre-digested’ as identical to the conservative dismissal of contemporary art, culture, and even values. Determined to take action, they scrawled ‘If Adorno is left in peace, capitalism will never cease’ on the blackboard. Three of them surrounded him and exposed their breasts as others handed out leaflets proclaiming, ‘Adorno as an institution is dead.’ Adorno would confide in Max Horkheimer, writing: ‘To have picked me of all people, I who have always spoken out against every type of erotic repression and sexual taboo!’

Academic, stuffy, German – Theodor W. Adorno has become emblematic of a certain sense of unfeeling in art. He was critical of TV, partial to Schoenberg, and aggrieved by the crassness of life in exile in 1940s America. Some of his students, infatuated with the youthful spontaneity of 1968, supposed that Adorno represented the old institutions that continued into post-war Europe, seeing his criticisms of mass culture being ‘pre-digested’ as identical to the conservative dismissal of contemporary art, culture, and even values. Determined to take action, they scrawled ‘If Adorno is left in peace, capitalism will never cease’ on the blackboard. Three of them surrounded him and exposed their breasts as others handed out leaflets proclaiming, ‘Adorno as an institution is dead.’ Adorno would confide in Max Horkheimer, writing: ‘To have picked me of all people, I who have always spoken out against every type of erotic repression and sexual taboo!’ And yet the issues on which Boas and Mead made their interventions, issues around race and gender, are now at the center of public life, and they bring all the nature-nurture confusion back with them. The focus of the conversation today is identity, and identity seems to be a concept that lies beyond both culture and biology. Is identity innate, or is it socially constructed? Is it fated, or can it be chosen or performed? Are our identities defined by the existing state of social relations, or do we carry them with us wherever we go?

And yet the issues on which Boas and Mead made their interventions, issues around race and gender, are now at the center of public life, and they bring all the nature-nurture confusion back with them. The focus of the conversation today is identity, and identity seems to be a concept that lies beyond both culture and biology. Is identity innate, or is it socially constructed? Is it fated, or can it be chosen or performed? Are our identities defined by the existing state of social relations, or do we carry them with us wherever we go? A

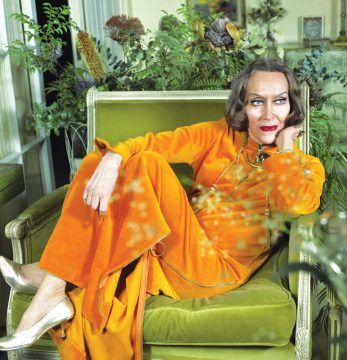

A One evening in early 1950, the film mogul Louis B. Mayer hosted a small dinner party for the actress Gloria Swanson. She was fifty-one years old, which was not considered an ancient, crone-like age, even in an industry that values youth above all else. Still, she was in need of a professional boost. Mayer’s small soiree was something of a ceremonial gesture. Here was one of the last tycoons of classic Hollywood extending his hand and his hospitality to an actress who was tottering, on marabou-covered heels, back into the business after a decade-long fermata.

One evening in early 1950, the film mogul Louis B. Mayer hosted a small dinner party for the actress Gloria Swanson. She was fifty-one years old, which was not considered an ancient, crone-like age, even in an industry that values youth above all else. Still, she was in need of a professional boost. Mayer’s small soiree was something of a ceremonial gesture. Here was one of the last tycoons of classic Hollywood extending his hand and his hospitality to an actress who was tottering, on marabou-covered heels, back into the business after a decade-long fermata.