Kate Kelly and Robin Pogrebin in The Atlantic:

Years ago, when she was practicing her closing arguments at the family dinner table, Martha Kavanaugh often returned to her signature line as a state prosecutor. “Use your common sense,” she’d say. “What rings true? What rings false?” Those words made a strong impression on her young son, Brett. They also made a strong impression on us, as we embarked on our 10-month investigation of the Supreme Court justice. We conducted hundreds of interviews with principal players in Kavanaugh’s education, career, and confirmation. We read thousands of documents. We reviewed hours of television interviews, along with reams of newspaper, magazine, and digital coverage. We studied maps of Montgomery Country, Maryland, as well as housing-renovation plans and court records. We watched Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearings multiple times. In reviewing our findings, we looked at them in two ways: through the prism of reporting and through the lens of common sense.

As women, we know that many sexual assaults aren’t corroborated. Many happen without witnesses, and many victims avoid reporting them out of shame or fear. But as reporters, we need evidence; we rely on the facts. Without corroboration, the claims of Christine Blasey Ford and Deborah Ramirez would be hard to accept. As women, we could not help but be moved by the accounts of Ford and Ramirez, and understand why they made such a lasting impact. As reporters, we had a responsibility to test those predilections. We had to offer Kavanaugh the benefit of the doubt, venturing to empathize with his suffering if he were falsely accused.

As mothers of daughters, we were prone to believe and support the women who spoke up. As mothers of sons, we had to imagine what it would be like if the men we loved were wrongly charged with these offenses.

As people, our gut reaction was that the allegations of Ford and Ramirez from the past rang true. As reporters, we uncovered nothing to suggest that Kavanaugh has mistreated women in the years since.

More here.

Exoplanet science has literally opened new worlds to study, with planets populating the galaxy unlike anything in our small solar system. Hot Jupiters whip around their stars in just days, burning at thousands of degrees. Super Earths—rocky planets that are more massive than our own—offer intriguing targets to study for signs of life. One planet, called K2-18b, sits approximately 110 light-years away from Earth. It’s larger than our planet, about 8.6 times the mass, and bigger in size at about 2.7 times the radius. These types of planets are commonly referred to as mini-Neptunes, thought to have rocky or icy cores surrounded by expansive atmospheres, and in recent years, scientists have found that they are extremely common across the galaxy.

Exoplanet science has literally opened new worlds to study, with planets populating the galaxy unlike anything in our small solar system. Hot Jupiters whip around their stars in just days, burning at thousands of degrees. Super Earths—rocky planets that are more massive than our own—offer intriguing targets to study for signs of life. One planet, called K2-18b, sits approximately 110 light-years away from Earth. It’s larger than our planet, about 8.6 times the mass, and bigger in size at about 2.7 times the radius. These types of planets are commonly referred to as mini-Neptunes, thought to have rocky or icy cores surrounded by expansive atmospheres, and in recent years, scientists have found that they are extremely common across the galaxy. I went to a school in Pakistan’s Punjab province called government primary school, Chak 2/4-L. Chak means village; 2/4-L is the name of my village, 2/4 the number of the canal feed that irrigates it, and L because it’s on the left side of the canal. Most villages along the canal had named themselves after a local legend or a landmark. We never bothered. I always assumed that our people were so hardworking they forgot to name where we lived.

I went to a school in Pakistan’s Punjab province called government primary school, Chak 2/4-L. Chak means village; 2/4-L is the name of my village, 2/4 the number of the canal feed that irrigates it, and L because it’s on the left side of the canal. Most villages along the canal had named themselves after a local legend or a landmark. We never bothered. I always assumed that our people were so hardworking they forgot to name where we lived. The Earth is heating up, and it’s our fault. But human beings are not always complete idiots (occasional contrary evidence notwithstanding), and sometimes we can even be downright clever. Dare we imagine that we can bring our self-inflicted climate catastrophe under control, through a combination of technological advances and political willpower? Ramez Naam is optimistic, at least about the technological advances. He is a technologist, entrepreneur, and science-fiction author, who has been following advances in renewable energy. We talk about the present state of solar, wind, and other renewable energy sources, and what our current rate of progress bodes for the near and farther future. And maybe we sneak in a little discussion of brain-computer interfaces, a theme of the Nexus trilogy.

The Earth is heating up, and it’s our fault. But human beings are not always complete idiots (occasional contrary evidence notwithstanding), and sometimes we can even be downright clever. Dare we imagine that we can bring our self-inflicted climate catastrophe under control, through a combination of technological advances and political willpower? Ramez Naam is optimistic, at least about the technological advances. He is a technologist, entrepreneur, and science-fiction author, who has been following advances in renewable energy. We talk about the present state of solar, wind, and other renewable energy sources, and what our current rate of progress bodes for the near and farther future. And maybe we sneak in a little discussion of brain-computer interfaces, a theme of the Nexus trilogy. The first murder came as a shock; the second suggested there might be a larger plot; by the third there was talk of government collusion; and when the fourth happened one felt it would not be the last. The victims—Narendra Dabholkar, Govind Pansare, M.M. Kalburgi, and Gauri Lankesh—were all killed in the same way, shot point-blank with a 7.65mm pistol by a gunman who came and fled on a two-wheeler. All beloved activists and thinkers, who wrote in the vernacular press, they had been vocal opponents of the BJP and its brand of Hindu nationalism. Their assassinations were meant to send a message, and far-right trolls on social media duly rejoiced. “One bitch died a dog’s death,” a man from Gujarat wrote on Twitter, referring to Lankesh; his account was followed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

The first murder came as a shock; the second suggested there might be a larger plot; by the third there was talk of government collusion; and when the fourth happened one felt it would not be the last. The victims—Narendra Dabholkar, Govind Pansare, M.M. Kalburgi, and Gauri Lankesh—were all killed in the same way, shot point-blank with a 7.65mm pistol by a gunman who came and fled on a two-wheeler. All beloved activists and thinkers, who wrote in the vernacular press, they had been vocal opponents of the BJP and its brand of Hindu nationalism. Their assassinations were meant to send a message, and far-right trolls on social media duly rejoiced. “One bitch died a dog’s death,” a man from Gujarat wrote on Twitter, referring to Lankesh; his account was followed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Kanders’s role as vice chairman of the Whitney’s board became a subject of intense agitation in the run-up to the show. In November, nearly a hundred Whitney staff members submitted a letter asking for his resignation, a demand later amplified by a petition signed by critics (including myself), academics, and artists (many of them Biennial participants); between January and March, the art activist group Decolonize This Place led weekly demonstrations at the museum. The curators directly addressed the controversy through their inclusion of the interdisciplinary research group Forensic Architecture’s much-written-about video Triple-Chaser, 2019, which also implicates Kanders through another of his holdings, Sierra Bullets, in child deaths and other war crimes in Israeli-occupied Palestinian territories. Superimposed on this debate over funding structures and museum ethics were a series of online skirmishes over art criticism, identity, and representation, touched off by Simone Leigh’s Instagram-based challenge to unnamed white critics who had characterized the Biennial as safe or lacking in “radicality” to question their narrow, racially conditioned frames of reference. In July, three black critics, Ciarán Finlayson, Tobi Haslett, and Hannah Black (who was a key polemicist in the representation-oriented clashes around the 2017 Biennial) coauthored a clear and powerful statement calling on Biennial artists to push for Kanders’s resignation by removing their work from the show. The statement, titled “The Tear Gas Biennial” and published on artforum.com, sharpened the contradictions between “the disembodied, declarative politics of art” and the material politics of its production, patronage, and circulation. “The ease with which left rhetoric flows from art is matched by a real poverty of conditions,” they wrote, “in which artists seem convinced they lack power in relation to the institutions their labor sustains. Now the highest aspiration of avowedly radical work is its own display.”

Kanders’s role as vice chairman of the Whitney’s board became a subject of intense agitation in the run-up to the show. In November, nearly a hundred Whitney staff members submitted a letter asking for his resignation, a demand later amplified by a petition signed by critics (including myself), academics, and artists (many of them Biennial participants); between January and March, the art activist group Decolonize This Place led weekly demonstrations at the museum. The curators directly addressed the controversy through their inclusion of the interdisciplinary research group Forensic Architecture’s much-written-about video Triple-Chaser, 2019, which also implicates Kanders through another of his holdings, Sierra Bullets, in child deaths and other war crimes in Israeli-occupied Palestinian territories. Superimposed on this debate over funding structures and museum ethics were a series of online skirmishes over art criticism, identity, and representation, touched off by Simone Leigh’s Instagram-based challenge to unnamed white critics who had characterized the Biennial as safe or lacking in “radicality” to question their narrow, racially conditioned frames of reference. In July, three black critics, Ciarán Finlayson, Tobi Haslett, and Hannah Black (who was a key polemicist in the representation-oriented clashes around the 2017 Biennial) coauthored a clear and powerful statement calling on Biennial artists to push for Kanders’s resignation by removing their work from the show. The statement, titled “The Tear Gas Biennial” and published on artforum.com, sharpened the contradictions between “the disembodied, declarative politics of art” and the material politics of its production, patronage, and circulation. “The ease with which left rhetoric flows from art is matched by a real poverty of conditions,” they wrote, “in which artists seem convinced they lack power in relation to the institutions their labor sustains. Now the highest aspiration of avowedly radical work is its own display.” The most buried things about us, apart from our self-deceits, our dreams are what we nevertheless do not shrink from sharing with strangers. They remain for us the strangest and most fascinating things about ourselves. We share them because of their striking originality, of which we hesitate to claim authorship.

The most buried things about us, apart from our self-deceits, our dreams are what we nevertheless do not shrink from sharing with strangers. They remain for us the strangest and most fascinating things about ourselves. We share them because of their striking originality, of which we hesitate to claim authorship. This is a book about creativity in the arts. Its thesis is opposed to the Romantic view of the artist as a lone genius who creates completely original works in flashes of inspired insight from the depths of his soul or deeply personal emotion. For the Romantic, the true genius’s work will violate all past conventions and practices in embodying a radically new concept. She creates this work in a moment of divine-like inspiration ex nihilo.

This is a book about creativity in the arts. Its thesis is opposed to the Romantic view of the artist as a lone genius who creates completely original works in flashes of inspired insight from the depths of his soul or deeply personal emotion. For the Romantic, the true genius’s work will violate all past conventions and practices in embodying a radically new concept. She creates this work in a moment of divine-like inspiration ex nihilo. W

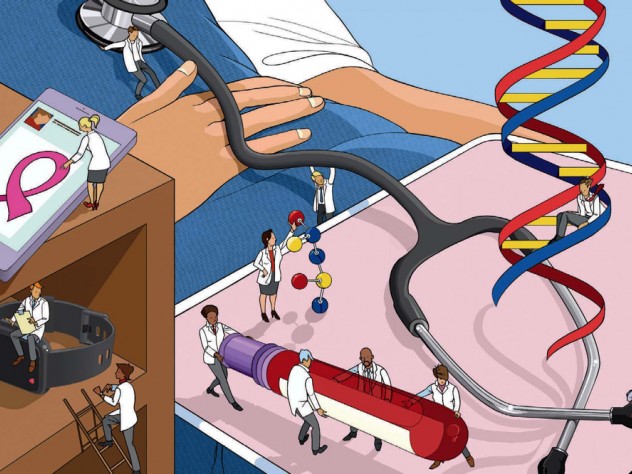

W Twenty years ago, the fight against cancer seemed as if it were about to take a dramatic turn.

Twenty years ago, the fight against cancer seemed as if it were about to take a dramatic turn. David Julius knows pain. The professor of physiology at the University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine has devoted his career to studying how the nervous system senses it and how chemicals such as capsaicin—the compound that gives chili peppers their heat—activates pain receptors. Julius was awarded a $3-million Breakthrough Prize in life sciences on Thursday for “discovering molecules, cells, and mechanisms underlying pain sensation.” Julius and his colleagues revealed how cell-membrane proteins called transient receptor potential (TRP) channels are involved in the perception of pain and heat or cold, as well as their role in inflammation and pain hypersensitivity. Much of his work has focused on the mechanism by which capsaicin exerts its potent effect on the human nervous system. His team identified the receptor responsive to capsaicin, TRPV1, and showed that it is also activated by heat and inflammatory chemicals. More recently, he has revealed how scorpion venom targets the “wasabi” receptor TRPA1. Drug developers are now investigating whether these receptors and others could be targeted to create nonopioid painkillers.

David Julius knows pain. The professor of physiology at the University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine has devoted his career to studying how the nervous system senses it and how chemicals such as capsaicin—the compound that gives chili peppers their heat—activates pain receptors. Julius was awarded a $3-million Breakthrough Prize in life sciences on Thursday for “discovering molecules, cells, and mechanisms underlying pain sensation.” Julius and his colleagues revealed how cell-membrane proteins called transient receptor potential (TRP) channels are involved in the perception of pain and heat or cold, as well as their role in inflammation and pain hypersensitivity. Much of his work has focused on the mechanism by which capsaicin exerts its potent effect on the human nervous system. His team identified the receptor responsive to capsaicin, TRPV1, and showed that it is also activated by heat and inflammatory chemicals. More recently, he has revealed how scorpion venom targets the “wasabi” receptor TRPA1. Drug developers are now investigating whether these receptors and others could be targeted to create nonopioid painkillers. Until I began the long and happy passage of reading all of Anton Chekhov’s short stories for the purpose of selecting the twenty for inclusion in The Essential Tales of Chekhov, I had read very little of Chekhov. It seems a terrible thing for a story writer to admit, and doubly worse for one whose own stories have been so thoroughly influenced by Chekhov through my relations with other writers who had been influenced by him directly: Sherwood Anderson. Isaac Babel. Hemingway. Cheever. Welty. Carver.

Until I began the long and happy passage of reading all of Anton Chekhov’s short stories for the purpose of selecting the twenty for inclusion in The Essential Tales of Chekhov, I had read very little of Chekhov. It seems a terrible thing for a story writer to admit, and doubly worse for one whose own stories have been so thoroughly influenced by Chekhov through my relations with other writers who had been influenced by him directly: Sherwood Anderson. Isaac Babel. Hemingway. Cheever. Welty. Carver. Nuclear energy is controversial among politicians, environmental activists, and investors. But new reactor designs, the immense energy-density of nuclear fuel, and the lack of carbon emissions make nuclear power attractive, if not crucial, amid growing energy demands and a changing climate.

Nuclear energy is controversial among politicians, environmental activists, and investors. But new reactor designs, the immense energy-density of nuclear fuel, and the lack of carbon emissions make nuclear power attractive, if not crucial, amid growing energy demands and a changing climate. There is a moment in Adrian Lyne’s film Lolita (1997) that is burned onto my memory. I was probably around 12, up late, watching it on terrestrial television. Lolita and her guardian, lover or captor have been moving between seedy motels, the romantic aesthetics waning until they wrestle on distressed sheets in a darkened room. The bed is covered with coins. Humbert has discovered Lolita has been stashing away the money he has ‘become accustomed’ to paying her, and he suddenly fears she is saving it in order to leave him, something that has not yet occurred to him. The shots are intimate, violent and jarring, ruptured by a later scene in which Lolita shouts: ‘I earned that money!’ We realise that Lolita has learned that sexual acts have monetary value.

There is a moment in Adrian Lyne’s film Lolita (1997) that is burned onto my memory. I was probably around 12, up late, watching it on terrestrial television. Lolita and her guardian, lover or captor have been moving between seedy motels, the romantic aesthetics waning until they wrestle on distressed sheets in a darkened room. The bed is covered with coins. Humbert has discovered Lolita has been stashing away the money he has ‘become accustomed’ to paying her, and he suddenly fears she is saving it in order to leave him, something that has not yet occurred to him. The shots are intimate, violent and jarring, ruptured by a later scene in which Lolita shouts: ‘I earned that money!’ We realise that Lolita has learned that sexual acts have monetary value. William Dalrymple’s

William Dalrymple’s