Michael Prodger in New Statesman:

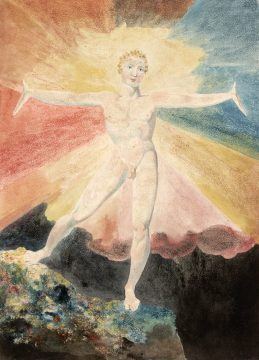

On February 1818, Samuel Taylor Cole-ridge was sent a copy of Songs of Innocence, William Blake’s first illustrated book of poems, which had been published some 30 years earlier. He was both impressed and discomfited by what he read. “You may smile at my calling another Poet a Mystic,” Coleridge, by then a fully fledged opium addict, wrote to a friend, “but verily I am in the very mire of commonplace common sense compared with Mr Blake.” Coleridge was not, of course, the first or last person to be mired.

On February 1818, Samuel Taylor Cole-ridge was sent a copy of Songs of Innocence, William Blake’s first illustrated book of poems, which had been published some 30 years earlier. He was both impressed and discomfited by what he read. “You may smile at my calling another Poet a Mystic,” Coleridge, by then a fully fledged opium addict, wrote to a friend, “but verily I am in the very mire of commonplace common sense compared with Mr Blake.” Coleridge was not, of course, the first or last person to be mired.

Blake’s offbeat character – from his naturism and convoluted, self-invented cosmology to his visions of angels sitting in trees and his political and religious nonconformism – forms a carapace so tough as to be nigh-on impenetrable. The fact that his quirks were not so much elements of the man but the man himself means that he can be too daunting to comprehend properly. He once said of his illustrated poems that “My style of designing is a species by itself” and Blake too can perhaps be best characterised as a species in himself.

Whatever Blake was – poet, prophet and sage, or “Rebel, Radical, Revolutionary” as the poster to Tate Britain’s extraordinary new survey of his career somewhat sensationally puts it – he was primarily, and from first to last, a professional artist. For much of his life he spent his days as a highly regarded freelance commercial engraver; his evenings he gave over to his watercolours and relief etchings – intended as saleable products; and it was only late at night that he became a poet, composing in snatches when he had a few moments to spare.

More here.

Nearly one-third of the wild birds in the United States and Canada have vanished since 1970, a staggering loss that suggests the very fabric of North America’s ecosystem is unraveling. The disappearance of 2.9 billion birds over the past nearly 50 years

Nearly one-third of the wild birds in the United States and Canada have vanished since 1970, a staggering loss that suggests the very fabric of North America’s ecosystem is unraveling. The disappearance of 2.9 billion birds over the past nearly 50 years

Back in 1996, a quantum physicist at Bell Labs in New Jersey published a new recipe for searching through a database of N entries. Computer scientists have long known that this process takes around N steps because in the worst case, the last item on the list could be the one of interest.

Back in 1996, a quantum physicist at Bell Labs in New Jersey published a new recipe for searching through a database of N entries. Computer scientists have long known that this process takes around N steps because in the worst case, the last item on the list could be the one of interest.

Six hours’ drive north of Disneyland, a building in downtown Oakland houses a kind of computer scientist’s version of the storied children’s amusement park. Its digital magic is of a less spectacular flavor, though; while Hollywood dreams of technofuturia in the style of vapory holograms, and Elon Musk promises to launch us skyward in

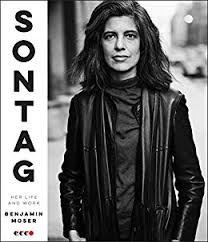

Six hours’ drive north of Disneyland, a building in downtown Oakland houses a kind of computer scientist’s version of the storied children’s amusement park. Its digital magic is of a less spectacular flavor, though; while Hollywood dreams of technofuturia in the style of vapory holograms, and Elon Musk promises to launch us skyward in  ‘Many who encountered the actual woman were disappointed to discover a reality far short of the glorious myth,’ Moser writes in his introduction. ‘Disappointment with her, indeed, is a prominent theme in memoirs of Sontag, not to mention in her own private writings.’ It is a salutary warning to readers who have bought into the notion of the dazzling, supremely confident intellectual. Eight hundred exhausting pages later, Sontag emerges as one of those irredeemably unhappy people, endlessly lurching between narcissism and self-hatred, who leave a string of uncomprehending friends, relatives and lovers in their wake. She wasn’t even interested in personal hygiene or health, forgetting to wash, wearing the same clothes for days at a time, smoking heavily and gorging herself on food at other people’s expense. A friend once arrived late for dinner with her at Petrossian on 58th Street, only to find that Sontag had already gone home, leaving him with the bill for the ‘sumptuous, multi-course caviar dinner’ she had consumed.

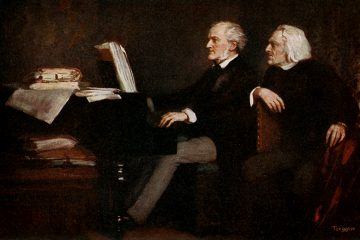

‘Many who encountered the actual woman were disappointed to discover a reality far short of the glorious myth,’ Moser writes in his introduction. ‘Disappointment with her, indeed, is a prominent theme in memoirs of Sontag, not to mention in her own private writings.’ It is a salutary warning to readers who have bought into the notion of the dazzling, supremely confident intellectual. Eight hundred exhausting pages later, Sontag emerges as one of those irredeemably unhappy people, endlessly lurching between narcissism and self-hatred, who leave a string of uncomprehending friends, relatives and lovers in their wake. She wasn’t even interested in personal hygiene or health, forgetting to wash, wearing the same clothes for days at a time, smoking heavily and gorging herself on food at other people’s expense. A friend once arrived late for dinner with her at Petrossian on 58th Street, only to find that Sontag had already gone home, leaving him with the bill for the ‘sumptuous, multi-course caviar dinner’ she had consumed. This focus on drama was fostered by Wagner’s upbringing, which included relatively little musical education. A painter and actor, his step-father Ludwig Geyer had taken young Richard to the theatre. Wagner did for a short while study composition in his home town of Leipzig. But he was never a proficient instrumentalist, which narrowed his path to a musical career. With what became his typical mixture of determination and cunning, he made a virtue out of necessity and simply declared the orchestra the grandest of instruments. (Indeed, he later wrote one of the first modern conducting manuals.) Above all, though, he learned on the job. In early 1833, at the age of nineteen, he began a series of seasonal engagements as chorus master and music director at various minor theatres as well as a touring company. These gave him valuable insights into the state of provincial opera performances, introduced him to the actress Minna Planer (soon to become his first wife), and opened the opportunity to mount a first operatic attempt. But he could not support the comfortable, silk-bedecked lifestyle he craved. Escaping his creditors, he spent two poverty-stricken but formative years in Paris, then the centre of the operatic world.

This focus on drama was fostered by Wagner’s upbringing, which included relatively little musical education. A painter and actor, his step-father Ludwig Geyer had taken young Richard to the theatre. Wagner did for a short while study composition in his home town of Leipzig. But he was never a proficient instrumentalist, which narrowed his path to a musical career. With what became his typical mixture of determination and cunning, he made a virtue out of necessity and simply declared the orchestra the grandest of instruments. (Indeed, he later wrote one of the first modern conducting manuals.) Above all, though, he learned on the job. In early 1833, at the age of nineteen, he began a series of seasonal engagements as chorus master and music director at various minor theatres as well as a touring company. These gave him valuable insights into the state of provincial opera performances, introduced him to the actress Minna Planer (soon to become his first wife), and opened the opportunity to mount a first operatic attempt. But he could not support the comfortable, silk-bedecked lifestyle he craved. Escaping his creditors, he spent two poverty-stricken but formative years in Paris, then the centre of the operatic world. Peter McNaughton, a professor of pharmacology at King’s College London, is a devoted optimist. He acknowledges that his positivity can sometimes seem irrational, but he also knows that without it he wouldn’t have achieved all that he has. And what he’s achieved is quite possibly monumental. After decades of research into the cellular basis of chronic pain, McNaughton believes he has discovered the fundamentals of a drug that might eradicate it. If he’s right, he could transform millions, even billions, of lives. What more could anyone hope for than a world without pain?

Peter McNaughton, a professor of pharmacology at King’s College London, is a devoted optimist. He acknowledges that his positivity can sometimes seem irrational, but he also knows that without it he wouldn’t have achieved all that he has. And what he’s achieved is quite possibly monumental. After decades of research into the cellular basis of chronic pain, McNaughton believes he has discovered the fundamentals of a drug that might eradicate it. If he’s right, he could transform millions, even billions, of lives. What more could anyone hope for than a world without pain? Several years ago, my father died as he had done most things throughout his life: without preparation and without consulting anyone. He simply went to bed one night, yielded his brain to a monstrous blood clot, and was found the next morning lying amidst the sheets like his own stone monument. It was hard for me not to take my father’s abrupt exit as a rebuke. For years, he’d been begging me to visit him in the Czech Republic, where I’d been born and where he’d gone back to live in 1992. Each year, I delayed. I was in that part of my life when the marriage-grad-school-children-career-divorce current was sweeping me along with breath-sucking force, and a leisurely trip to the fatherland seemed as plausible as pausing the flow of time. Now my dad was shrugging at me from beyond— “You see, you’ve run out of time.”

Several years ago, my father died as he had done most things throughout his life: without preparation and without consulting anyone. He simply went to bed one night, yielded his brain to a monstrous blood clot, and was found the next morning lying amidst the sheets like his own stone monument. It was hard for me not to take my father’s abrupt exit as a rebuke. For years, he’d been begging me to visit him in the Czech Republic, where I’d been born and where he’d gone back to live in 1992. Each year, I delayed. I was in that part of my life when the marriage-grad-school-children-career-divorce current was sweeping me along with breath-sucking force, and a leisurely trip to the fatherland seemed as plausible as pausing the flow of time. Now my dad was shrugging at me from beyond— “You see, you’ve run out of time.” In

In  Most people rarely deal with irrational numbers—it would be, well, irrational, as they run on forever, and representing them accurately requires an infinite amount of space. But irrational constants such as π and √2—numbers that cannot be reduced to a simple fraction—frequently crop up in science and engineering. These unwieldy numbers have plagued mathematicians since the ancient Greeks; indeed, legend has it that Hippasus was

Most people rarely deal with irrational numbers—it would be, well, irrational, as they run on forever, and representing them accurately requires an infinite amount of space. But irrational constants such as π and √2—numbers that cannot be reduced to a simple fraction—frequently crop up in science and engineering. These unwieldy numbers have plagued mathematicians since the ancient Greeks; indeed, legend has it that Hippasus was  Across the world, the right has, for the past decades, celebrated a remarkable string of successes. Far-right populists are now in power in countries from the United States to India, and from Turkey to Brazil. Even most of the democracies in which right-wing extremists remain comparatively weak are ruled by right-of-center, or at most centrist, leaders: Angela Merkel is now in the 14th year of her chancellorship in Germany, Scott Morrison was recently reelected in Australia, and Emmanuel Macron is the President of France.

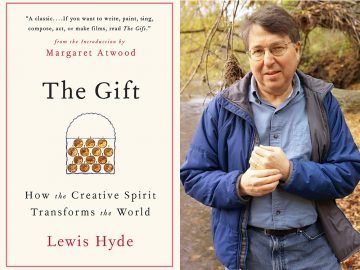

Across the world, the right has, for the past decades, celebrated a remarkable string of successes. Far-right populists are now in power in countries from the United States to India, and from Turkey to Brazil. Even most of the democracies in which right-wing extremists remain comparatively weak are ruled by right-of-center, or at most centrist, leaders: Angela Merkel is now in the 14th year of her chancellorship in Germany, Scott Morrison was recently reelected in Australia, and Emmanuel Macron is the President of France. The Gift has never been out of print; it moves like an underground current among artists of all kinds, through word of mouth and bestowal. It is the one book I recommend without fail to aspiring writers and painters and musicians, for it is not a how-to book—there are many of these—but a book about the core nature of what it is that artists do, and also about the relation of these activities to our overwhelmingly commercial society. If you want to write, paint, sing, compose, act, or make films, read The Gift. It will help to keep you sane.

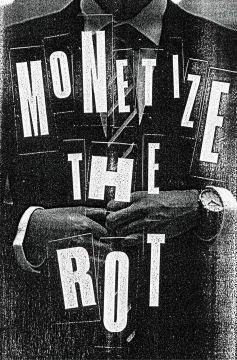

The Gift has never been out of print; it moves like an underground current among artists of all kinds, through word of mouth and bestowal. It is the one book I recommend without fail to aspiring writers and painters and musicians, for it is not a how-to book—there are many of these—but a book about the core nature of what it is that artists do, and also about the relation of these activities to our overwhelmingly commercial society. If you want to write, paint, sing, compose, act, or make films, read The Gift. It will help to keep you sane. Mainstream media outlets tend to skip those details when they talk about privatization, as if a corporation is a sentient monolith and not run by individual human beings like McKesson chief executive officer John H. Hammergren, who in 2011 was paid more money than any other CEO in America. He retired at the end of March and will reportedly receive a $114 million pension, in addition to other benefits worth nearly $25 million. While vets struggle to get competent treatment for depression and service members live in houses with mice and mold, Hammergren’s home, until recently, was a 23,000-square-foot compound in Contra Costa County that included a rock climbing wall; courts for tennis, bocce ball, racquetball, and squash; a car wash; and a yoga center. He sold it last year for three times the $3 million he bought it for in 1996. (He had been hoping to sell it for seven times as much.)

Mainstream media outlets tend to skip those details when they talk about privatization, as if a corporation is a sentient monolith and not run by individual human beings like McKesson chief executive officer John H. Hammergren, who in 2011 was paid more money than any other CEO in America. He retired at the end of March and will reportedly receive a $114 million pension, in addition to other benefits worth nearly $25 million. While vets struggle to get competent treatment for depression and service members live in houses with mice and mold, Hammergren’s home, until recently, was a 23,000-square-foot compound in Contra Costa County that included a rock climbing wall; courts for tennis, bocce ball, racquetball, and squash; a car wash; and a yoga center. He sold it last year for three times the $3 million he bought it for in 1996. (He had been hoping to sell it for seven times as much.) And it’s his music, and his equally affecting artwork, that Johnston should be remembered for. That’s why I’ve resisted till now touching upon what the word “outsider” really means when we speak of him. It’s a euphemism, a somewhat awkward way of acknowledging his schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Since Jeff Feuerzeig’s powerful 2005 documentary The Devil and Daniel Johnston, the singer’s mental health issues have been central to his myth, to the point that the knowledge of them threatens to overshadow his accomplishments. What I mean is that “True Love Will Find You in the End” is a great song – not just “great for a crazy guy”. I think Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy said it best a couple of years ago in an interview with the New York Times: “Daniel has managed to create in spite of his mental illness, not because of it. He’s been honest in his portrayal of what he’s been struggling with without overtly drawing attention to it.”

And it’s his music, and his equally affecting artwork, that Johnston should be remembered for. That’s why I’ve resisted till now touching upon what the word “outsider” really means when we speak of him. It’s a euphemism, a somewhat awkward way of acknowledging his schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Since Jeff Feuerzeig’s powerful 2005 documentary The Devil and Daniel Johnston, the singer’s mental health issues have been central to his myth, to the point that the knowledge of them threatens to overshadow his accomplishments. What I mean is that “True Love Will Find You in the End” is a great song – not just “great for a crazy guy”. I think Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy said it best a couple of years ago in an interview with the New York Times: “Daniel has managed to create in spite of his mental illness, not because of it. He’s been honest in his portrayal of what he’s been struggling with without overtly drawing attention to it.”