A Greeting on the Trail

Turning fifty, at last I come to understand,

belatedly, unexpectedly, and quite suddenly,

that poetry is not going to save anybody’s life,

least of all my own. Nonetheless I choose to believe

the journey is not a descent but a climb,

as when, in a forest of golden-green morning sunlight,

one sees another hiker on the trail, who calls out,

where are you bound, friend, to the valley or the mountaintop?

Many things—seaweed, pollen, attention—drift.

News of the universe’s origin infiltrates atom by atom

the oxygenated envelope of the atmosphere.

My sense of purpose vectors away on rash currents

like the buoys I find tossed on the beach after a storm,

cork bobbers torn from old crab traps.

And what befalls the woebegotten crabs,

caged and forgotten at the bottom of the sea?

Are the labors to which we are summoned by dreams

so different from the tasks to which the sunlight of reality

enslaves us? One tires of niceties. We sleep now

surrounded by books, books piled in heaps

by the bedside, stacked along the walls of the room.

Let dust accrue on their spines and colophons,

let their ragged towers rise and wobble.

Of course the Chinese poets were familiar with all this,

T’ao Ch’ien, Hsieh Ling-yün, Po Chü-i,

masterful sophisticates adopting common accents

for their nostalgic drinking songs and laments

to age and temple ruins, imperial avarice,

autumn leaves caught in a tumbling stream.

As the river flows at the urging of gravity, as a flower

blooms after April rain, we are implements

of the unseen, always working for someone else.

The boss is a tall woman in a sky-blue shirt

or a man with one thumb lost to a cross-cut saw

or science or art or the emperor, what matter?

We scrabble within the skin of time

like mice in the belly of a boa constrictor,

Jonah within leviathan, pacing the keel, rib to rib,

surrounded by the pulse of that enormous, compassionate heart.

Later we dance in orchards of guava and lychee nuts

to the shifting registers of distant music,

a clattering of plates as great fish are lifted from the grill,

seared black with bitter orange and lemongrass.

Orchid trees bloom here, Tulip trees and Flame trees,

but no Idea trees, no trees of Mercy,

for these are human capacities, human occasions.

Because it has about it something of the old village magic,

the crop made to rise by seed of words,

by spell or incantation—

because it frightens and humbles us to recall

our submission to such protocols—

for this do we fear poetry, for the unresolved darkness

of the past. Where are you bound, friend,

on this bright and fruitful morning—to the valley

or the mountaintop? To the mountaintop.

.

by Campbell McGrath

from the Kenyon Review

Throughout modern history, the weight of Western colonialism in the name of freedom and religious liberty has distorted the nature of the Middle East. It has transformed the political geography of the region by creating a series of small and dependent Middle Eastern states and emirates where once stood a large interconnected Ottoman sultanate. It introduced a new – and still unresolved – conflict between ‘Arab’ and ‘Jew’ in Palestine just when a new Arab identity that included Muslim, Christian and Jewish Arabs appeared most promising. This late – last – Western colonialism has obscured the fact that the shift from Ottoman imperial rule to post-Ottoman Arab national rule was neither natural nor inevitable. European colonialism abruptly interrupted and reshaped a vital anti-sectarian Arab cultural and political path that had begun to take shape during the last century of Ottoman rule. Despite European colonialism, the ecumenical ideal, and the dream of creating sovereign societies greater than the sum of their communal or sectarian parts, survived well into the 20th-century Arab world.

Throughout modern history, the weight of Western colonialism in the name of freedom and religious liberty has distorted the nature of the Middle East. It has transformed the political geography of the region by creating a series of small and dependent Middle Eastern states and emirates where once stood a large interconnected Ottoman sultanate. It introduced a new – and still unresolved – conflict between ‘Arab’ and ‘Jew’ in Palestine just when a new Arab identity that included Muslim, Christian and Jewish Arabs appeared most promising. This late – last – Western colonialism has obscured the fact that the shift from Ottoman imperial rule to post-Ottoman Arab national rule was neither natural nor inevitable. European colonialism abruptly interrupted and reshaped a vital anti-sectarian Arab cultural and political path that had begun to take shape during the last century of Ottoman rule. Despite European colonialism, the ecumenical ideal, and the dream of creating sovereign societies greater than the sum of their communal or sectarian parts, survived well into the 20th-century Arab world. The major cause of cancer-related deaths is the spread of cancer cells from their primary site to other parts of the body

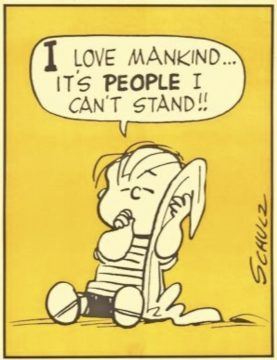

The major cause of cancer-related deaths is the spread of cancer cells from their primary site to other parts of the body Here’s where it begins for me: a four-panel strip, Lucy and Linus, simplest narrative in the universe. As the sequence starts, we see Lucy skipping rope and, like an older sister, giving Linus a hard time. “You a doctor! Ha! That’s a big laugh!” she mocks. “You could never be a doctor! You know why?” Before he can respond, she turns away, as if to say she knows him better than he knows himself. “Because you don’t love mankind, that’s why!” she answers, seeking (as usual) the final word. Linus, however, he defies her, standing alone in the last frame, shouting his rejoinder out into the distance: “I love mankind . . . it’s people I can’t stand!!”

Here’s where it begins for me: a four-panel strip, Lucy and Linus, simplest narrative in the universe. As the sequence starts, we see Lucy skipping rope and, like an older sister, giving Linus a hard time. “You a doctor! Ha! That’s a big laugh!” she mocks. “You could never be a doctor! You know why?” Before he can respond, she turns away, as if to say she knows him better than he knows himself. “Because you don’t love mankind, that’s why!” she answers, seeking (as usual) the final word. Linus, however, he defies her, standing alone in the last frame, shouting his rejoinder out into the distance: “I love mankind . . . it’s people I can’t stand!!” As a doctor who treats cancer, I think a lot about how to frame new treatments to my patients. I never want to give false hope. But the uncertainty inherent to my field also cautions me against closing the door on optimism prematurely. We take it as a point of pride that no field of medicine evolves as rapidly as cancer — the FDA approves dozens of new treatments a year. One of my biggest challenges is staying up to date on every development and teasing apart what should — and shouldn’t — change my practice. I am often a mediator for my patients, tempering theoretical promises with everyday realism. To accept a research finding into medical practice, I prefer slow steps showing me proof of concept, safety, and efficacy.

As a doctor who treats cancer, I think a lot about how to frame new treatments to my patients. I never want to give false hope. But the uncertainty inherent to my field also cautions me against closing the door on optimism prematurely. We take it as a point of pride that no field of medicine evolves as rapidly as cancer — the FDA approves dozens of new treatments a year. One of my biggest challenges is staying up to date on every development and teasing apart what should — and shouldn’t — change my practice. I am often a mediator for my patients, tempering theoretical promises with everyday realism. To accept a research finding into medical practice, I prefer slow steps showing me proof of concept, safety, and efficacy. I was raised as a Quaker, but around the age of 20 my faith faded. It would be easiest to say that this was because I took up philosophy – my lifelong occupation as a teacher and scholar. This is not true. More accurately, I joke that having had one headmaster in this life, I’ll be damned if I want another in the next. I was convinced back then that, by the age of 70, I would be getting back onside with the Powers That Be. But faith did not then return and, as I approach 80, is nowhere on the horizon. I feel more at peace with myself than ever before. It’s not that I don’t care about the meaning or purpose of life – I am a philosopher! Nor does my sense of peace mean that I am complacent or that I have delusions about my achievements and successes. Rather, I feel that deep contentment that religious people tell us is the gift or reward for proper living.

I was raised as a Quaker, but around the age of 20 my faith faded. It would be easiest to say that this was because I took up philosophy – my lifelong occupation as a teacher and scholar. This is not true. More accurately, I joke that having had one headmaster in this life, I’ll be damned if I want another in the next. I was convinced back then that, by the age of 70, I would be getting back onside with the Powers That Be. But faith did not then return and, as I approach 80, is nowhere on the horizon. I feel more at peace with myself than ever before. It’s not that I don’t care about the meaning or purpose of life – I am a philosopher! Nor does my sense of peace mean that I am complacent or that I have delusions about my achievements and successes. Rather, I feel that deep contentment that religious people tell us is the gift or reward for proper living. Ptacin, the author of the memoir “Poor Your Soul,” herself hovers somewhere between curiosity and the edge of belief. As she tells us, she wants to believe, wishes she could see the ghosts that float so readily around the Maine mediums in this “enchanted hamlet.” But the hovering serves a purpose. She is on a quest to understand the peculiar nature of belief, the power of faith — pure, unquestioning and even unreasoning — to shape the way we see the world around us.

Ptacin, the author of the memoir “Poor Your Soul,” herself hovers somewhere between curiosity and the edge of belief. As she tells us, she wants to believe, wishes she could see the ghosts that float so readily around the Maine mediums in this “enchanted hamlet.” But the hovering serves a purpose. She is on a quest to understand the peculiar nature of belief, the power of faith — pure, unquestioning and even unreasoning — to shape the way we see the world around us. It’s not just that Nesbit’s books are brilliant: her life is also brilliant material for one. She was in person at once quite awe-inspiring and a bit of a nightmare, able to weather tragedy and yet a queen of melodrama, a self-supporting writer who opposed women’s suffrage. Vibrantly attractive and adored by her many proteges and readers, she was what they called in those days “advanced” – a committed socialist (she and her husband Hubert Bland were among the earliest members of

It’s not just that Nesbit’s books are brilliant: her life is also brilliant material for one. She was in person at once quite awe-inspiring and a bit of a nightmare, able to weather tragedy and yet a queen of melodrama, a self-supporting writer who opposed women’s suffrage. Vibrantly attractive and adored by her many proteges and readers, she was what they called in those days “advanced” – a committed socialist (she and her husband Hubert Bland were among the earliest members of Dimitrina Petrova in Dissent:

Dimitrina Petrova in Dissent: Over at the Next System Project’s

Over at the Next System Project’s  Steven Wishnia in The Indypendent:

Steven Wishnia in The Indypendent: Robert Zaretsky in Foreign Affairs:

Robert Zaretsky in Foreign Affairs: This wonderful book might be read as a long meditation on WH Auden’s notorious throwaway comment in his elegy for WB Yeats: “Poetry makes nothing happen.” John Burnside’s first chapter engages directly with this maxim, patiently showing us what it does and does not mean in its context. Auden is not shrugging his shoulders and accepting a place for poetry at the neglected margins of social life. Rather he is making a stark distinction between the ways in which human beings try to “make things happen” – the feverish efforts at political and technological control – and the tough imperative to find ways of echoing “the music of what is” in word and gesture.

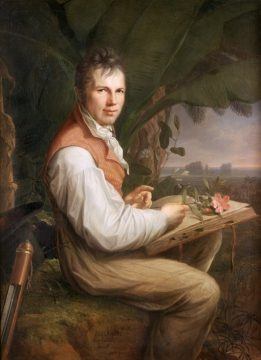

This wonderful book might be read as a long meditation on WH Auden’s notorious throwaway comment in his elegy for WB Yeats: “Poetry makes nothing happen.” John Burnside’s first chapter engages directly with this maxim, patiently showing us what it does and does not mean in its context. Auden is not shrugging his shoulders and accepting a place for poetry at the neglected margins of social life. Rather he is making a stark distinction between the ways in which human beings try to “make things happen” – the feverish efforts at political and technological control – and the tough imperative to find ways of echoing “the music of what is” in word and gesture. Who’s the “father” of environmentalism? Now that the human impact on nature is getting more attention than ever, it’s a question worth asking. Is it, for example, the Prussian naturalist, Alexander von Humboldt, as his biographer thinks?

Who’s the “father” of environmentalism? Now that the human impact on nature is getting more attention than ever, it’s a question worth asking. Is it, for example, the Prussian naturalist, Alexander von Humboldt, as his biographer thinks? “HU!! HU!! HU!!,” yelled the crowd, at escalating volume, for a full 20 minutes before the Hu kicked off their recent concert at the Brooklyn venue, Warsaw. The fans who packed the place, many of whom were decked out in de rigueur heavy metal gear of black T-shirts and leather, thrust their fists into the air in rhythm to their chants, which grew to a roar the moment the band appeared.

“HU!! HU!! HU!!,” yelled the crowd, at escalating volume, for a full 20 minutes before the Hu kicked off their recent concert at the Brooklyn venue, Warsaw. The fans who packed the place, many of whom were decked out in de rigueur heavy metal gear of black T-shirts and leather, thrust their fists into the air in rhythm to their chants, which grew to a roar the moment the band appeared. Scientists at Google on Wednesday declared,

Scientists at Google on Wednesday declared,