Viviane Callier in The Scientist:

From Alaska down to the Baja Peninsula, the rocky tide pools of North America’s West Coast are separated by hundreds of kilometers of sandy beaches. Inside those tide pools live Tigriopus californicus copepods, small shrimp-like animals that evolutionary biologist Ron Burton has been studying since he was an undergraduate at Stanford University in the 1970s. During those early days of DNA technology, Burton became curious how the genomes of the isolated copepod populations compared.

From Alaska down to the Baja Peninsula, the rocky tide pools of North America’s West Coast are separated by hundreds of kilometers of sandy beaches. Inside those tide pools live Tigriopus californicus copepods, small shrimp-like animals that evolutionary biologist Ron Burton has been studying since he was an undergraduate at Stanford University in the 1970s. During those early days of DNA technology, Burton became curious how the genomes of the isolated copepod populations compared.

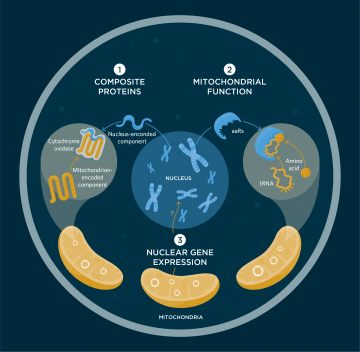

While still at Stanford, Burton sequenced the mitochondrial gene cytochrome c oxidase subunit one, the standard marker people used at the time for species identification, and discovered that the copepod populations were strongly differentiated: on average, there was a 20 percent sequence divergence in this gene between populations. When he crossed Santa Cruz copepods with animals from San Diego, the hybrids did fine, but when he bred them to one another, their offspring did not do well, taking longer to develop, producing fewer offspring, and having lower survival. “That was the first indication that there was some sort of genetic incompatibility developing between these isolated populations,” says Burton, now a professor at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego.

More here. [Thanks to Jonathan Beams.]

According to the

According to the  IN 1940, FOUR TEENAGE BOYS

IN 1940, FOUR TEENAGE BOYS As anyone

As anyone The submarine

The submarine  Dan Nexon over at the book’s website:

Dan Nexon over at the book’s website: “Trust me”: It’s a tired cliché, a throwaway line, but when you first encounter it in “A Warning,” the

“Trust me”: It’s a tired cliché, a throwaway line, but when you first encounter it in “A Warning,” the  In 1928 Margaret Mead published Coming of Age in Samoa in which she argued that the sulks and slammed doors of American teens had nothing to do with their hormones and everything to do with their picket-fenced parents. By way of evidence 27-year-old Mead used the findings from her recent anthropological fieldwork in the South Pacific. Samoan adolescents, she explained, were happy growing up to be just like Mum and Dad. There was no thought of rebellion, because there was nothing to rebel against. Gender was generously accommodating to girly-boys and boyish girls and, while monogamy was fine in principle, it was nothing to get steamed up about if you fell a bit short. As if this weren’t all thrilling enough, Mead’s publisher put a picture of a topless Samoan woman on the cover of her book. Naturally, it was a bestseller.

In 1928 Margaret Mead published Coming of Age in Samoa in which she argued that the sulks and slammed doors of American teens had nothing to do with their hormones and everything to do with their picket-fenced parents. By way of evidence 27-year-old Mead used the findings from her recent anthropological fieldwork in the South Pacific. Samoan adolescents, she explained, were happy growing up to be just like Mum and Dad. There was no thought of rebellion, because there was nothing to rebel against. Gender was generously accommodating to girly-boys and boyish girls and, while monogamy was fine in principle, it was nothing to get steamed up about if you fell a bit short. As if this weren’t all thrilling enough, Mead’s publisher put a picture of a topless Samoan woman on the cover of her book. Naturally, it was a bestseller. In the late 1950s, Marcel Breuer took on a commission to design a church in Minnesota. He was working with the engineer Pier Luigi Nervi. The result of Breuer and Nevi’s efforts is one of the most terrifying structures ever built.

In the late 1950s, Marcel Breuer took on a commission to design a church in Minnesota. He was working with the engineer Pier Luigi Nervi. The result of Breuer and Nevi’s efforts is one of the most terrifying structures ever built.

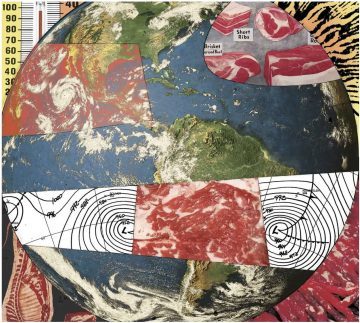

Over the last few years we have seen a veritable cottage industry of essays by novelists turned climate catastrophists: Jonathan Franzen in The New Yorker writing on birds and how inevitable the coming collapse is, Michael Chabon in The Paris Review lamenting that his art residency has not changed the world, Nathaniel Rich in The New York Times Magazine offering us an obituary for climate policy-making. The climate sad bois abound, bringing us an important truth that they believe they alone have discovered and that alone can deliver the world from catastrophe, or at least confer on them some sort of personal absolution as the planet burns. Stop hoping and start growing kale and strawberries, Franzen tells us. Make art, Chabon suggests. All of this is to say that there are a great many voices that have been missing from the public conversation about the climate crisis, but none of them are Jonathan Safran Foer’s.

Over the last few years we have seen a veritable cottage industry of essays by novelists turned climate catastrophists: Jonathan Franzen in The New Yorker writing on birds and how inevitable the coming collapse is, Michael Chabon in The Paris Review lamenting that his art residency has not changed the world, Nathaniel Rich in The New York Times Magazine offering us an obituary for climate policy-making. The climate sad bois abound, bringing us an important truth that they believe they alone have discovered and that alone can deliver the world from catastrophe, or at least confer on them some sort of personal absolution as the planet burns. Stop hoping and start growing kale and strawberries, Franzen tells us. Make art, Chabon suggests. All of this is to say that there are a great many voices that have been missing from the public conversation about the climate crisis, but none of them are Jonathan Safran Foer’s. Emily and I exchange techniques to stop crying. There comes a time, we say, when one is simply not in the mood. Pick a color, she tells me, and find every instance of it in the room. I pick blue. I pick dark green. One day I call her and say that if I start to cry I want her to squawk like a chicken. When my voice starts to shake she panics and quacks like a duck. Then I am laughing and crying all at once—wet and loud and thankful—and it feels as if my heart has turned itself inside out.

Emily and I exchange techniques to stop crying. There comes a time, we say, when one is simply not in the mood. Pick a color, she tells me, and find every instance of it in the room. I pick blue. I pick dark green. One day I call her and say that if I start to cry I want her to squawk like a chicken. When my voice starts to shake she panics and quacks like a duck. Then I am laughing and crying all at once—wet and loud and thankful—and it feels as if my heart has turned itself inside out. In the same season that Human Flow was making the rounds of art house theaters in the United States, the great French Nouvelle Vague filmmaker Agnès Varda was collaborating with the artist JR on Faces Places (Visages, Villages). In the film, Varda and JR (like Weiwei, an installation artist) travel rural France meeting with waitresses, mailmen, miners, and factory workers, and photographing them in JR’s mobile photo booth. These portraits are then enlarged and pasted to the buildings that they work and live in—barns, abandoned homes, shipping containers—creating dramatic pop-up artworks.

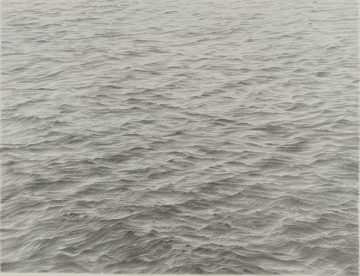

In the same season that Human Flow was making the rounds of art house theaters in the United States, the great French Nouvelle Vague filmmaker Agnès Varda was collaborating with the artist JR on Faces Places (Visages, Villages). In the film, Varda and JR (like Weiwei, an installation artist) travel rural France meeting with waitresses, mailmen, miners, and factory workers, and photographing them in JR’s mobile photo booth. These portraits are then enlarged and pasted to the buildings that they work and live in—barns, abandoned homes, shipping containers—creating dramatic pop-up artworks. Such work, mimetic in nature, necessitates an abandonment of the world. To scribe, to spend hours of one’s day, every day, copying the words of another artist or, as in Celmins’s practice, painstakingly copying the details of an object and, at the same time, attempting to remove all trace of one’s self, requires the artist to enter the object, and, in doing so, to leave the world. Akin to a small death, this practice is meditative in nature. In trauma, the mind leaves the body, dissociating, as a means to protect one’s psyche from the traumatic event. One antidote to this is to focus on one object: grounding one’s self in the present moment. Over the years, Celmins’s work has become more committed to the practice of fixing herself to the image. In this way, she folds herself into the work the same way the object she is copying is folded into the artwork. As Walter Benjamin writes in “On Copy,” “a copy can be understood as a memory.” Literally, when one makes a copy, one creates a memory of the original object. Indeed, Celmins’s art is deeply rooted in the work of memory: both the labor-intensive work of scribing, which presses the work being copied into the memory of scribe’s mind, and the act of copying, which results, as Benjamin writes, in a memory.

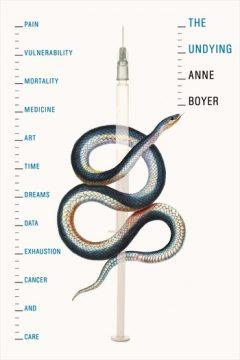

Such work, mimetic in nature, necessitates an abandonment of the world. To scribe, to spend hours of one’s day, every day, copying the words of another artist or, as in Celmins’s practice, painstakingly copying the details of an object and, at the same time, attempting to remove all trace of one’s self, requires the artist to enter the object, and, in doing so, to leave the world. Akin to a small death, this practice is meditative in nature. In trauma, the mind leaves the body, dissociating, as a means to protect one’s psyche from the traumatic event. One antidote to this is to focus on one object: grounding one’s self in the present moment. Over the years, Celmins’s work has become more committed to the practice of fixing herself to the image. In this way, she folds herself into the work the same way the object she is copying is folded into the artwork. As Walter Benjamin writes in “On Copy,” “a copy can be understood as a memory.” Literally, when one makes a copy, one creates a memory of the original object. Indeed, Celmins’s art is deeply rooted in the work of memory: both the labor-intensive work of scribing, which presses the work being copied into the memory of scribe’s mind, and the act of copying, which results, as Benjamin writes, in a memory. “I was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014, at the age of forty-one,” the poet Anne Boyer writes early in her panoramic, book-length essay The Undying. Elemental and unadorned, the sentence does not leap out for quotation, and in the context of a review of some other essay, some other book, summary would be adequate (“At the age of forty-one, the poet Anne Boyer . . .”). But in a story about breast cancer, the voice of the speaker is consequential and Boyer makes this plain when, in consulting other women writers who suffered from the disease, she observes whether or not they have used the first person. Audre Lorde, for example, in The Cancer Journals (1980), her cancer memoir avant la lettre, has. Susan Sontag, who wrote Illness as Metaphor (1978) while being treated for the disease, has not. Boyer remarks on these choices not to find fault with them but to stress that decisions regarding whether and how to write about breast cancer are among its many agonies. The disease, she tells us, presents as “a disordering question of form.”

“I was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014, at the age of forty-one,” the poet Anne Boyer writes early in her panoramic, book-length essay The Undying. Elemental and unadorned, the sentence does not leap out for quotation, and in the context of a review of some other essay, some other book, summary would be adequate (“At the age of forty-one, the poet Anne Boyer . . .”). But in a story about breast cancer, the voice of the speaker is consequential and Boyer makes this plain when, in consulting other women writers who suffered from the disease, she observes whether or not they have used the first person. Audre Lorde, for example, in The Cancer Journals (1980), her cancer memoir avant la lettre, has. Susan Sontag, who wrote Illness as Metaphor (1978) while being treated for the disease, has not. Boyer remarks on these choices not to find fault with them but to stress that decisions regarding whether and how to write about breast cancer are among its many agonies. The disease, she tells us, presents as “a disordering question of form.” Even if all the world agreed on the reality of anthropogenic global warming and on the gravity of the consequences for life on our planet, further difficult questions would arise. How are the needs of future generations to be balanced against the sufferings of people living today? How exactly are the potential perils of a seriously heated earth to be avoided? How are the burdens and costs to be distributed? How is the international cooperation required to be forged and sustained? As Evelyn Fox Keller and I argue in The Seasons Alter (2017), all these questions need to be posed, distinguished, and answered if the human population is to extricate itself from the mess some of its members have made (often unwittingly, though today in full consciousness).

Even if all the world agreed on the reality of anthropogenic global warming and on the gravity of the consequences for life on our planet, further difficult questions would arise. How are the needs of future generations to be balanced against the sufferings of people living today? How exactly are the potential perils of a seriously heated earth to be avoided? How are the burdens and costs to be distributed? How is the international cooperation required to be forged and sustained? As Evelyn Fox Keller and I argue in The Seasons Alter (2017), all these questions need to be posed, distinguished, and answered if the human population is to extricate itself from the mess some of its members have made (often unwittingly, though today in full consciousness).