Phil Christman in The Hedgehog Review:

I watch bad movies, a pastime and a passion I have long shared with my father. When I was a child, we would sit on one of a series of couches scavenged from yard sales or curbsides, eating microwave popcorn while watching, say, Teenagers from Outer Space (1959) or Zontar, the Thing from Venus (1962). My father would set the VCR to tape movies like these in the middle of the night from the sorts of TV channels that programmed them, with palpable desperation, between reruns of The Incredible Hulk and camcordered ads for local mattress-store chains. Amusement, like couches, had to be taken where found.

I watch bad movies, a pastime and a passion I have long shared with my father. When I was a child, we would sit on one of a series of couches scavenged from yard sales or curbsides, eating microwave popcorn while watching, say, Teenagers from Outer Space (1959) or Zontar, the Thing from Venus (1962). My father would set the VCR to tape movies like these in the middle of the night from the sorts of TV channels that programmed them, with palpable desperation, between reruns of The Incredible Hulk and camcordered ads for local mattress-store chains. Amusement, like couches, had to be taken where found.

Ours was neither a wholly singular nor widely shared hobby. A few years later, the television series Mystery Science Theater 3000 made text of this subtext: Its framing device consisted of a man and two robots cracking wise over the soundtrack as bad movies played onscreen. It was important that the man wasn’t simply alone, and that, at the same time, he was somewhat isolated: a Crusoe-like figure alone on a satellite, forced to build himself a minisociety of talking robots. Watching bad movies was a social yet marginal activity; it was a way of watching that orbited the normal enjoyment of film.

In the canon of bad films, Ed Wood’s Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959) is the anticlassic. On the satellite where bad-movie watchers gather, it is our Citizen Kane, our Seven Samurai, and in the ages before Amazon, you had to really search to find it.

More here.

In 1882, linguists were electrified by the publication of a lost language—one supposedly spoken by the extinct Taensa people of Louisiana—because it bore hardly any relation to the languages of other Native American peoples of that region. The Taensa grammar was so unusual they were convinced it could teach them something momentous either about the region’s history, or the way that languages evolve, or both.

In 1882, linguists were electrified by the publication of a lost language—one supposedly spoken by the extinct Taensa people of Louisiana—because it bore hardly any relation to the languages of other Native American peoples of that region. The Taensa grammar was so unusual they were convinced it could teach them something momentous either about the region’s history, or the way that languages evolve, or both. The crowd at Elizabeth Warren’s rally in New York City in September was enthusiastic throughout, but it was her proposed new wealth tax—2 percent on wealth above $50 million, rising to 3 percent above $1 billion—that got them chanting: “Two cents! Two Cents! Two Cents!” Bernie Sanders has proposed a similar wealth tax, with rates peaking at 8 percent above $5 billion. In the October Democratic debate, a number of centrist candidates were open to it, and even Joe Biden, who seemed to reject one, argued for eliminating the favorable tax treatment of capital gains and raising income tax rates for the rich.

The crowd at Elizabeth Warren’s rally in New York City in September was enthusiastic throughout, but it was her proposed new wealth tax—2 percent on wealth above $50 million, rising to 3 percent above $1 billion—that got them chanting: “Two cents! Two Cents! Two Cents!” Bernie Sanders has proposed a similar wealth tax, with rates peaking at 8 percent above $5 billion. In the October Democratic debate, a number of centrist candidates were open to it, and even Joe Biden, who seemed to reject one, argued for eliminating the favorable tax treatment of capital gains and raising income tax rates for the rich. Many of us desperately want to preserve the thing we call nature or wilderness. But because we’ve destroyed so much, it is a slippery business to save what remains. If we don’t erect predator-proof fences, the world will lose the rabbit-eared bandicoot, a marsupial rodent with giant ears and a long pink nose. And we’ll lose the Newell’s shearwater, a seabird that brays like a donkey and dives down 150feet to catch squid. If we dobuild the fences, we lose the luxuriant creative abandon that produced these creatures. We create a demonstration plot of what once was.

Many of us desperately want to preserve the thing we call nature or wilderness. But because we’ve destroyed so much, it is a slippery business to save what remains. If we don’t erect predator-proof fences, the world will lose the rabbit-eared bandicoot, a marsupial rodent with giant ears and a long pink nose. And we’ll lose the Newell’s shearwater, a seabird that brays like a donkey and dives down 150feet to catch squid. If we dobuild the fences, we lose the luxuriant creative abandon that produced these creatures. We create a demonstration plot of what once was. Re-reading is often deemed comfort reading, and of course it can be. But books that are embedded in your history are rich in association, and picking them up often retriggers the emotions they provoked the first time, emotions allied to the feeling of being young. Comfort reading can be the most uncomfortable kind of all. I remember buying The Honourable Schoolboy at a bookshop in Newcastle that no longer exists; I remember taking it on a marathon coach journey, the length of the country; and I remember reading much of it in my first ever hammock in blistering sunshine – my first foreign holiday, not far from Nîmes. Similarly, it matters to me that my copy of Smiley’s People – a first edition given to me as a birthday gift – is identical to the one I borrowed from my local library in 1979 or 80. When I pick it up, I feel my younger self tugging at my sleeve, asking for his book back.

Re-reading is often deemed comfort reading, and of course it can be. But books that are embedded in your history are rich in association, and picking them up often retriggers the emotions they provoked the first time, emotions allied to the feeling of being young. Comfort reading can be the most uncomfortable kind of all. I remember buying The Honourable Schoolboy at a bookshop in Newcastle that no longer exists; I remember taking it on a marathon coach journey, the length of the country; and I remember reading much of it in my first ever hammock in blistering sunshine – my first foreign holiday, not far from Nîmes. Similarly, it matters to me that my copy of Smiley’s People – a first edition given to me as a birthday gift – is identical to the one I borrowed from my local library in 1979 or 80. When I pick it up, I feel my younger self tugging at my sleeve, asking for his book back.

I

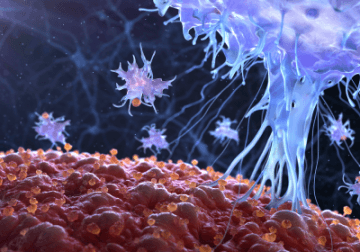

I Preliminary research suggests that using CRISPR to treat cancer is safe in humans and could become a feasible therapeutic method in the future, although its efficacy is still unknown. Results from an ongoing clinical trial, led by hematologist Edward Stadtmauer of the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, will be presented at the American Society of Hematology meeting in December. The presentation abstract was published

Preliminary research suggests that using CRISPR to treat cancer is safe in humans and could become a feasible therapeutic method in the future, although its efficacy is still unknown. Results from an ongoing clinical trial, led by hematologist Edward Stadtmauer of the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, will be presented at the American Society of Hematology meeting in December. The presentation abstract was published  Once upon a time in Italy, a prominent citizen declared: “It is unacceptable that sometimes in certain parts of Milan there is such a presence of non-Italians that instead of thinking you are in an Italian or European city, you think you are in an African city.”

Once upon a time in Italy, a prominent citizen declared: “It is unacceptable that sometimes in certain parts of Milan there is such a presence of non-Italians that instead of thinking you are in an Italian or European city, you think you are in an African city.” The author of blueprint, Robert Plomin is an American psychologist, geneticist and neuroscientist and perhaps the most important voice, over many years, in the field of behavioral genetics. It is difficult today to imaging how scientifically taboo it was to study the genetics of human behavior after the racist horrors, bogus research and eugenics projects carried out by the Germans in the Nazi period. The field of behavioral genetics got off to a politically rocky beginning in the 1960s, but has gradually gained respectability, although some of its applications, particularly in the area of race, have been controversial (I would argue, misguided). The great achievement of the field is to show without any doubt that understanding human behavior must include the factor of genetic predispositions. Robert Plomin is to be admired for his contributions and his courage. What he writes deserves attention.

The author of blueprint, Robert Plomin is an American psychologist, geneticist and neuroscientist and perhaps the most important voice, over many years, in the field of behavioral genetics. It is difficult today to imaging how scientifically taboo it was to study the genetics of human behavior after the racist horrors, bogus research and eugenics projects carried out by the Germans in the Nazi period. The field of behavioral genetics got off to a politically rocky beginning in the 1960s, but has gradually gained respectability, although some of its applications, particularly in the area of race, have been controversial (I would argue, misguided). The great achievement of the field is to show without any doubt that understanding human behavior must include the factor of genetic predispositions. Robert Plomin is to be admired for his contributions and his courage. What he writes deserves attention. Is the deepening animosity between Democrats and Republicans based on genuine differences over policy and ideology or is it a form of tribal warfare rooted in an atavistic us-versus-them mentality?

Is the deepening animosity between Democrats and Republicans based on genuine differences over policy and ideology or is it a form of tribal warfare rooted in an atavistic us-versus-them mentality? Kerschen’s depiction of the on-the-ground historical conditions that produced the Romantics’ most radical poetry—Shelley’s “Epipsychidion” and “The Masque of Anarchy,” Byron’s Don Juan—is a major achievement. But the book also offers an appealingly intimate view into Keats’s more mundane realities. The convalescent poet is forced to reckon with his debts, both financial and emotional: his life in Italy is dependent on his friends’ charity, and he is pressured to honor his engagement to Fanny Brawne, back in London. The author’s research is impeccable: the fictional Keats’s traits are all supported by what manuscript evidence tells us about the poet’s character. Even so, his choices often come as a pleasant surprise.

Kerschen’s depiction of the on-the-ground historical conditions that produced the Romantics’ most radical poetry—Shelley’s “Epipsychidion” and “The Masque of Anarchy,” Byron’s Don Juan—is a major achievement. But the book also offers an appealingly intimate view into Keats’s more mundane realities. The convalescent poet is forced to reckon with his debts, both financial and emotional: his life in Italy is dependent on his friends’ charity, and he is pressured to honor his engagement to Fanny Brawne, back in London. The author’s research is impeccable: the fictional Keats’s traits are all supported by what manuscript evidence tells us about the poet’s character. Even so, his choices often come as a pleasant surprise. J

J Halfway through Sorry We Missed You, Ken Loach’s latest excursion into breadline Britain and a companion piece to his career-rejuvenating I, Daniel Blake, Abby (Debbie Honeywood) is recounting a nightmare in which she and her husband Ricky (Kris Hitchen) are stuck in quicksand. Their children, 11-year-old Lisa Jane (Katie Proctor) and 15-year-old Seb (Rhys Stone), try to pull them out but the more the adults struggle, the deeper they sink. There’s not much point in Abby mulling over the meaning of this, and no need to run it past a therapist. She and Ricky are workers in the gig economy, the instability of employment eating away at their wellbeing. “It’ll be different in six months,” is their plaintive mantra as they pile more hours on to their working week.

Halfway through Sorry We Missed You, Ken Loach’s latest excursion into breadline Britain and a companion piece to his career-rejuvenating I, Daniel Blake, Abby (Debbie Honeywood) is recounting a nightmare in which she and her husband Ricky (Kris Hitchen) are stuck in quicksand. Their children, 11-year-old Lisa Jane (Katie Proctor) and 15-year-old Seb (Rhys Stone), try to pull them out but the more the adults struggle, the deeper they sink. There’s not much point in Abby mulling over the meaning of this, and no need to run it past a therapist. She and Ricky are workers in the gig economy, the instability of employment eating away at their wellbeing. “It’ll be different in six months,” is their plaintive mantra as they pile more hours on to their working week. There’s no Wuthering Heights, no Moby-Dick, no Ulysses, but there is Half of a Yellow Sun, Bridget Jones’s Diary and Discworld: so announced the panel of experts assembled by the

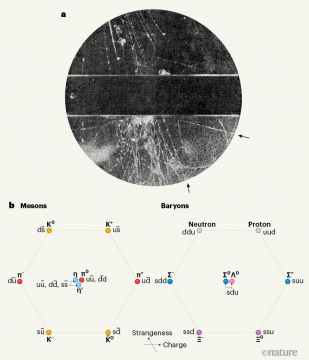

There’s no Wuthering Heights, no Moby-Dick, no Ulysses, but there is Half of a Yellow Sun, Bridget Jones’s Diary and Discworld: so announced the panel of experts assembled by the  In the late 1940s, the physicists George Rochester and Clifford Butler

In the late 1940s, the physicists George Rochester and Clifford Butler

James Duesterberg at The Point:

Holloway invokes the story of Frankenstein’s monster, which is often taken as an allegory for capitalism. Frankenstein, a mad scientist who creates an artificial man, spends most of his story chasing after his invention or being chased by him; like a regulatory agency, the best he can do is damage control.

more here.