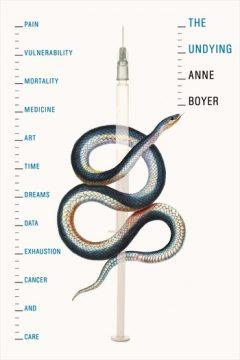

Sarah Resnick in Bookforum:

“I was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014, at the age of forty-one,” the poet Anne Boyer writes early in her panoramic, book-length essay The Undying. Elemental and unadorned, the sentence does not leap out for quotation, and in the context of a review of some other essay, some other book, summary would be adequate (“At the age of forty-one, the poet Anne Boyer . . .”). But in a story about breast cancer, the voice of the speaker is consequential and Boyer makes this plain when, in consulting other women writers who suffered from the disease, she observes whether or not they have used the first person. Audre Lorde, for example, in The Cancer Journals (1980), her cancer memoir avant la lettre, has. Susan Sontag, who wrote Illness as Metaphor (1978) while being treated for the disease, has not. Boyer remarks on these choices not to find fault with them but to stress that decisions regarding whether and how to write about breast cancer are among its many agonies. The disease, she tells us, presents as “a disordering question of form.”

“I was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014, at the age of forty-one,” the poet Anne Boyer writes early in her panoramic, book-length essay The Undying. Elemental and unadorned, the sentence does not leap out for quotation, and in the context of a review of some other essay, some other book, summary would be adequate (“At the age of forty-one, the poet Anne Boyer . . .”). But in a story about breast cancer, the voice of the speaker is consequential and Boyer makes this plain when, in consulting other women writers who suffered from the disease, she observes whether or not they have used the first person. Audre Lorde, for example, in The Cancer Journals (1980), her cancer memoir avant la lettre, has. Susan Sontag, who wrote Illness as Metaphor (1978) while being treated for the disease, has not. Boyer remarks on these choices not to find fault with them but to stress that decisions regarding whether and how to write about breast cancer are among its many agonies. The disease, she tells us, presents as “a disordering question of form.”

Before the 1970s, the subject of breast cancer was all but taboo, the disease stigmatized. Written traces of the illness could be found mostly in medical narratives, where men (doctors) were the actors and women mere hosts to the drama’s antagonists (tumors, metastases). Those who had been diagnosed would scarcely utter “I” and “breast cancer” in the same sentence. Women said little on the subject in part because they were not asked to. They were also fearful: A stubborn, long-standing conviction branded the ill personally responsible for what ailed them. (This is, of course, in part the subject of Sontag’s book.) The medical treatment then most common, the radical mastectomy, was disfiguring and, what’s more, seemed not to influence the outcome of a diagnosis. Death from the disease was reputed to be stealthy—and terrifying.

It was into this void, this vacant room, that women began to speak: first in the columns of women’s magazines (Ladies’ Home Journal, McCall’s, and Vogue), then in the headlines of national newspapers; first lady Betty Ford’s candor about her diagnosis and radical mastectomy, in 1974, made front-page news. Over time, the pronoun “I” would become essential, its invocation seemingly sure to lead to awareness, early detection, fewer women falling ill—and to fewer women acquiescing to life-altering, unnecessary surgeries. The logic, empowering and intoxicating, was soon formalized into charities and fundraising events, among the first of these the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation’s inaugural Race for the Cure in Dallas in 1983.

More here.