Antonia Malchik in Aeon:

Antonia Malchik in Aeon:

One evening in 1992, my parents, younger sister and I sat on the fold-out futon on the living room floor, petting our cats and watching fires consume buildings in Los Angeles. The images that spilled from the screen are only vague memories now: a dark night, broken windows, police sirens echoing, people rampaging across the city and leaving destruction in their wake. I was 16 years old. Having mostly grown up in small-town Montana without access to cable television, this was one of my first experiences watching a national news story on live TV.

The event we were watching, often called the LA riots, was triggered by the acquittal of police officers who had been filmed beating a construction worker named Rodney King. The eruption took its place in a long line of other violent uprisings against racial and gender injustice – the Watts riots, the Stonewall riots, and the 12th Street riot in Detroit. In my little hometown, TV viewers were prompted to view such riots through the lens of irrational ‘crowd contagion’ – a long-debunked perspective that nonetheless pervaded the media coverage in the first days of the LA event, until deeper analysis reflected on the searing racial tensions, inequality and poverty that triggered the uprising.

More here.

A “VISIONARY,” A “PROPHET,” A “MODERN-DAY LEONARDO”: Writers often resort to panegyrics when confronted with the eccentric, daunting intellect of Agnes Denes. Given the ambition of the octogenarian artist’s career, which spans fifty years and emerges from deep research into philosophy, mathematics, symbolic logic, and environmental science, it’s hard to fault them.

A “VISIONARY,” A “PROPHET,” A “MODERN-DAY LEONARDO”: Writers often resort to panegyrics when confronted with the eccentric, daunting intellect of Agnes Denes. Given the ambition of the octogenarian artist’s career, which spans fifty years and emerges from deep research into philosophy, mathematics, symbolic logic, and environmental science, it’s hard to fault them. I

I It’s astonishing that humans are expected to make our way in the world with language alone. “To speak is an incomparable act / of faith,” the poet Craig Morgan Teicher has written. “What proof do we have / that when I say mouse, you do not think / of a stop sign?”

It’s astonishing that humans are expected to make our way in the world with language alone. “To speak is an incomparable act / of faith,” the poet Craig Morgan Teicher has written. “What proof do we have / that when I say mouse, you do not think / of a stop sign?” Gordon Marino teaches philosophy at St. Olaf College and curates the Hong Kierkegaard Library. He has spent decades writing about the existentialists. His passion for them did not begin in the classroom, though. After a failed relationship, with derailed careers in both boxing and academic philosophy, a young Marino strugged with suicidal thoughts. While waiting for a counseling session, he spotted a copy of Søren Kierkegaard’s Works of Love on a coffee-shop bookshelf. He opened it to a passage in which Kierkegaard criticizes a “conceited sagacity” that refuses to believe in love. Intrigued, Marino hid Works of Love under his coat on the way out the door. He credits the book with saving his life. “At the risk of seeming histrionic,” Marino writes, “there was a time when Kierkegaard grabbed me by the shoulder and pulled me back from the crossbeam and the rope.” In Kierkegaard and other existentialists, Marino found philosophers who wrote in the first person, took moods and emotions seriously, and kept up a staring contest with despair. While these eclectic thinkers often had qualms about the professoriate, they led Marino back to academic philosophy. He returned with an older conception of philosophy as a way of life and a pursuit of wisdom, a conception the existentialists helped renew and one that animates this compelling study of them.

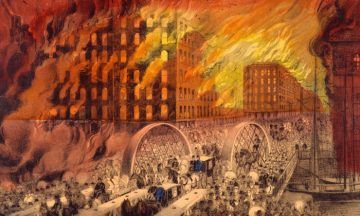

Gordon Marino teaches philosophy at St. Olaf College and curates the Hong Kierkegaard Library. He has spent decades writing about the existentialists. His passion for them did not begin in the classroom, though. After a failed relationship, with derailed careers in both boxing and academic philosophy, a young Marino strugged with suicidal thoughts. While waiting for a counseling session, he spotted a copy of Søren Kierkegaard’s Works of Love on a coffee-shop bookshelf. He opened it to a passage in which Kierkegaard criticizes a “conceited sagacity” that refuses to believe in love. Intrigued, Marino hid Works of Love under his coat on the way out the door. He credits the book with saving his life. “At the risk of seeming histrionic,” Marino writes, “there was a time when Kierkegaard grabbed me by the shoulder and pulled me back from the crossbeam and the rope.” In Kierkegaard and other existentialists, Marino found philosophers who wrote in the first person, took moods and emotions seriously, and kept up a staring contest with despair. While these eclectic thinkers often had qualms about the professoriate, they led Marino back to academic philosophy. He returned with an older conception of philosophy as a way of life and a pursuit of wisdom, a conception the existentialists helped renew and one that animates this compelling study of them. Called shikaakwa by the Miami-Illinois tribe for the skunky smell of the wild-onion that grew on the banks of Lake Michigan, “Chicago” is a French transcription of the earlier name for the area. Founded in 1833, with an initial population of 350, before the fire, it is said, Chicago’s streets curved around the Lake Michigan waterfront and followed the course of the Chicago River and a network of cattle paths lain over Native American migration routes. In contrast to the organic form of the city associated with the early settlers, modern Chicago would be organized as a grid, with address numbers (beginning in 1909) that could tell any pedestrian where they were in relationship to the central point (0,0) of State and Madison streets. According to plan, the modules of this new grid, great skyscrapers, grew up from the rubble like gigantic, up-stretched skeletons of cast iron and, later, steel. The grid, “a framework of spaced parallel bars” according to the Oxford American Dictionary, appears here as the image of an emerging modernity.

Called shikaakwa by the Miami-Illinois tribe for the skunky smell of the wild-onion that grew on the banks of Lake Michigan, “Chicago” is a French transcription of the earlier name for the area. Founded in 1833, with an initial population of 350, before the fire, it is said, Chicago’s streets curved around the Lake Michigan waterfront and followed the course of the Chicago River and a network of cattle paths lain over Native American migration routes. In contrast to the organic form of the city associated with the early settlers, modern Chicago would be organized as a grid, with address numbers (beginning in 1909) that could tell any pedestrian where they were in relationship to the central point (0,0) of State and Madison streets. According to plan, the modules of this new grid, great skyscrapers, grew up from the rubble like gigantic, up-stretched skeletons of cast iron and, later, steel. The grid, “a framework of spaced parallel bars” according to the Oxford American Dictionary, appears here as the image of an emerging modernity. Democracy is hard work. If it is to function well, citizens must do a lot of thinking and talking about politics. But democracy is demanding in another way as well. It requires us to maintain a peculiar moral posture toward our fellow citizens. We must acknowledge that they’re our equals and thus entitled to an equal say, even when their views are severely misguided. It seems a lot to ask.

Democracy is hard work. If it is to function well, citizens must do a lot of thinking and talking about politics. But democracy is demanding in another way as well. It requires us to maintain a peculiar moral posture toward our fellow citizens. We must acknowledge that they’re our equals and thus entitled to an equal say, even when their views are severely misguided. It seems a lot to ask. To search for Polanyi’s intellectual and political roots means coming into contact with a bewilderingly febrile left-wing intellectual milieu that appears to have little bearing on our present. However promising the current moment may seem with a self-described “democratic socialist” coming tantalizingly close to winning the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination, Gareth Dale’s new biography offers us a bracing reminder of a far richer world of socialist activity that once existed in much of the West. Debates over early-20th-century Hungarian socialism; the strategic plans of “Red Vienna”; the reformist 1961 platform of the Soviet Communist Party: These questions obsessed Polanyi and his contemporaries to a degree that seems almost inconceivable now and certainly residing in a sobering distance to our own immediate lives. Polanyi’s political activism and intellectual work were implicated in the widest questions debated on the left. The son of wealthy Hungarian Jews, he emerged as part of the “Great Generation” of Hungarian artists and intellectuals in Budapest at around the turn of the 20th century. John von Neumann, the mathematician, and Béla Bartók, the composer, were his contemporaries; so were the sociologist Karl Mannheim and the Marxist theoretician and literary critic György Lukács. Polanyi’s brother, Michael, became a philosopher of science, who for many years was better known than Karl.

To search for Polanyi’s intellectual and political roots means coming into contact with a bewilderingly febrile left-wing intellectual milieu that appears to have little bearing on our present. However promising the current moment may seem with a self-described “democratic socialist” coming tantalizingly close to winning the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination, Gareth Dale’s new biography offers us a bracing reminder of a far richer world of socialist activity that once existed in much of the West. Debates over early-20th-century Hungarian socialism; the strategic plans of “Red Vienna”; the reformist 1961 platform of the Soviet Communist Party: These questions obsessed Polanyi and his contemporaries to a degree that seems almost inconceivable now and certainly residing in a sobering distance to our own immediate lives. Polanyi’s political activism and intellectual work were implicated in the widest questions debated on the left. The son of wealthy Hungarian Jews, he emerged as part of the “Great Generation” of Hungarian artists and intellectuals in Budapest at around the turn of the 20th century. John von Neumann, the mathematician, and Béla Bartók, the composer, were his contemporaries; so were the sociologist Karl Mannheim and the Marxist theoretician and literary critic György Lukács. Polanyi’s brother, Michael, became a philosopher of science, who for many years was better known than Karl.

Over the past decade, Americans have debated the best way to fix our broken healthcare system, one that allows

Over the past decade, Americans have debated the best way to fix our broken healthcare system, one that allows  Boris Orman, who worked at a bakery, provides a typical example. In mid-1937, even as the whirlwind of Stalin’s purges surged across the country, Orman shared the following anekdot (joke) with a colleague over tea in the bakery cafeteria:

Boris Orman, who worked at a bakery, provides a typical example. In mid-1937, even as the whirlwind of Stalin’s purges surged across the country, Orman shared the following anekdot (joke) with a colleague over tea in the bakery cafeteria: One of the most famous vehicles in literature is coming to the Smithsonian’s

One of the most famous vehicles in literature is coming to the Smithsonian’s  When I was a Jewish kid growing up in suburban Los Angeles, we thought being Jewish meant supporting Israel.

When I was a Jewish kid growing up in suburban Los Angeles, we thought being Jewish meant supporting Israel. This work attending to the fullness of creation has revealed astounding complexity. As we walk through the forest, we notice plants and animals around us, but often we literally miss the forest’s interconnections for the trees. The greatest part of its biodiversity lies below ground, where thousands upon thousands of species of worms, arthropods, and insects live, each hosting a different bacterial community in its gut. We used to think of soil as a test tube full of chemicals, but now know that it’s a complex biological network; we are only beginning to understand its thousands of parts. These are “trophic” networks: who eats what and whom. The complexity goes far beyond predator and prey. Everything from a fallen evergreen needle to a tree is consumed, and the droppings of the consumers are consumed by yet other species through cycles upon cycles.

This work attending to the fullness of creation has revealed astounding complexity. As we walk through the forest, we notice plants and animals around us, but often we literally miss the forest’s interconnections for the trees. The greatest part of its biodiversity lies below ground, where thousands upon thousands of species of worms, arthropods, and insects live, each hosting a different bacterial community in its gut. We used to think of soil as a test tube full of chemicals, but now know that it’s a complex biological network; we are only beginning to understand its thousands of parts. These are “trophic” networks: who eats what and whom. The complexity goes far beyond predator and prey. Everything from a fallen evergreen needle to a tree is consumed, and the droppings of the consumers are consumed by yet other species through cycles upon cycles.