Arianne Chernok at Public Books:

In part, the distaste for thinking critically about the monarchy stems from an unlikely source. In the 1960s and 70s, social history and women’s history pioneered a “history from below,” ushering in not only a disciplinary but also an ethical imperative, one that quickly spread to neighboring fields both inside and outside the academy. A balancing swing has begun in recent years—Clarissa Campbell Orr, a historian of queenship, proclaimed in 2002 that “much is to be gained for women’s history and feminist history by looking at women at the social apex, including their roles, representations and symbolic importance for other men and women”—though studies of the elite, and especially of the monarchy (the ultra-elite), can still be regarded with considerable suspicion.4 Taking on the monarchy is too often mistakenly viewed as a willingness to embrace rather than to interrogate. This is particularly true for those conducting research in modern history, where records are available for subjects from a range of social classes and backgrounds. (Few, for example, would object to using Queen Elizabeth I as a focal point for a study of gender in Tudor England, given the paucity of other sources about women’s lives from that period.) In this context, to write about Queen Elizabeth II, or about the Windsors more generally, smacks not just of elitism but also of commercialism—a crass bid to boost sales and gain a broader readership.

In part, the distaste for thinking critically about the monarchy stems from an unlikely source. In the 1960s and 70s, social history and women’s history pioneered a “history from below,” ushering in not only a disciplinary but also an ethical imperative, one that quickly spread to neighboring fields both inside and outside the academy. A balancing swing has begun in recent years—Clarissa Campbell Orr, a historian of queenship, proclaimed in 2002 that “much is to be gained for women’s history and feminist history by looking at women at the social apex, including their roles, representations and symbolic importance for other men and women”—though studies of the elite, and especially of the monarchy (the ultra-elite), can still be regarded with considerable suspicion.4 Taking on the monarchy is too often mistakenly viewed as a willingness to embrace rather than to interrogate. This is particularly true for those conducting research in modern history, where records are available for subjects from a range of social classes and backgrounds. (Few, for example, would object to using Queen Elizabeth I as a focal point for a study of gender in Tudor England, given the paucity of other sources about women’s lives from that period.) In this context, to write about Queen Elizabeth II, or about the Windsors more generally, smacks not just of elitism but also of commercialism—a crass bid to boost sales and gain a broader readership.

more here.

And, indeed, Gibson stopped setting his novels mainly in the far future around the turn of the millennium. He changed mode. “Since Pattern Recognition I’ve been writing novels of the recent past. They’ve tended to be published in the year after they actually take place. After the publication of All Tomorrow’s Parties [1999] I had a feeling that my game was sagging a bit. Not that there’s anything particularly wrong with that book – but I felt that I was losing a sense of how weird the real world around me was. Because I was busy writing novels and whatever, and I’d sort of glance out of the window at the day’s reality and I’d go: ‘Whoah! That was really strange.’ Then I’d look back down at my page and realise that that was stranger than my page, and I began to feel … uneasy.”

And, indeed, Gibson stopped setting his novels mainly in the far future around the turn of the millennium. He changed mode. “Since Pattern Recognition I’ve been writing novels of the recent past. They’ve tended to be published in the year after they actually take place. After the publication of All Tomorrow’s Parties [1999] I had a feeling that my game was sagging a bit. Not that there’s anything particularly wrong with that book – but I felt that I was losing a sense of how weird the real world around me was. Because I was busy writing novels and whatever, and I’d sort of glance out of the window at the day’s reality and I’d go: ‘Whoah! That was really strange.’ Then I’d look back down at my page and realise that that was stranger than my page, and I began to feel … uneasy.”

Social perception bias

Social perception bias A great deal of recent public debate about artificial intelligence has been driven by apocalyptic visions of the future. Humanity, we are told, is engaged in an existential struggle against its own creation. Such worries are fueled in large part by tech industry leaders and futurists, who anticipate systems so sophisticated that they can perform general tasks and operate autonomously, without human control. Stephen Hawking, Elon Musk, and Bill Gates have all publicly

A great deal of recent public debate about artificial intelligence has been driven by apocalyptic visions of the future. Humanity, we are told, is engaged in an existential struggle against its own creation. Such worries are fueled in large part by tech industry leaders and futurists, who anticipate systems so sophisticated that they can perform general tasks and operate autonomously, without human control. Stephen Hawking, Elon Musk, and Bill Gates have all publicly  I didn’t know it

I didn’t know it The great French historian and resistance martyr, Marc Bloch, is supposed to have said that history was like a knife: You can cut bread with it, but you could also kill. This is even more true of historical derivatives like analogies; they can provide either illumination or poisonous polemic. The first requirement for an acceptable historical analogy is plausibility; the two situations compared must have striking similarities, and the image of the historic antecedent must be as clearly understood as possible. This becomes an unlikely presupposition when the analogy is proposed by partisans working in an age of stunning historical ignorance. Nowadays, politicians and partisans use analogies instead of arguments, convenient shorthand for their defenses of dubious policies.

The great French historian and resistance martyr, Marc Bloch, is supposed to have said that history was like a knife: You can cut bread with it, but you could also kill. This is even more true of historical derivatives like analogies; they can provide either illumination or poisonous polemic. The first requirement for an acceptable historical analogy is plausibility; the two situations compared must have striking similarities, and the image of the historic antecedent must be as clearly understood as possible. This becomes an unlikely presupposition when the analogy is proposed by partisans working in an age of stunning historical ignorance. Nowadays, politicians and partisans use analogies instead of arguments, convenient shorthand for their defenses of dubious policies. On its surface, The House of Mirth reads like a 19th-century novel. Although the 20th century’s defining technologies had all been invented by the time it was published in 1905, they had yet to substantially alter even the affluent world of the novel’s protagonist, Lily Bart. Cars were exotic playthings; telephones hadn’t supplanted visiting cards; electric light was a harsher alternative to candles. The first world war was inconceivable. And there is, too, a lingering 19th-century feel to Wharton’s disembodied approach to human physicality – especially striking in a novel whose central conundrum is sexual: Lily, a pedigreed virgin without fortune, craves the sensual pleasures of life among the very rich but cannot bring herself to marry a wealthy man, her only means of securing those pleasures for life.

On its surface, The House of Mirth reads like a 19th-century novel. Although the 20th century’s defining technologies had all been invented by the time it was published in 1905, they had yet to substantially alter even the affluent world of the novel’s protagonist, Lily Bart. Cars were exotic playthings; telephones hadn’t supplanted visiting cards; electric light was a harsher alternative to candles. The first world war was inconceivable. And there is, too, a lingering 19th-century feel to Wharton’s disembodied approach to human physicality – especially striking in a novel whose central conundrum is sexual: Lily, a pedigreed virgin without fortune, craves the sensual pleasures of life among the very rich but cannot bring herself to marry a wealthy man, her only means of securing those pleasures for life. Australia is in the grip of its worst wildfire season on record. The human death toll stands at 27, and some 2,000 homes have been destroyed across more than 10 million hectares of land — an area larger than Portugal. An estimated 1 billion wild mammals, birds and reptiles have perished. Michael Clarke, an ecologist at La Trobe University in Bundoora, Melbourne, has been studying the effect of fires on native ecosystems — and how they recover — ever since a fire tore through his field site 15 years ago. Clarke spoke to Nature about how animals fare in the wake of wildfires, and why this season’s fires could prove particularly devastating.

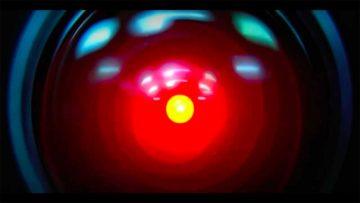

Australia is in the grip of its worst wildfire season on record. The human death toll stands at 27, and some 2,000 homes have been destroyed across more than 10 million hectares of land — an area larger than Portugal. An estimated 1 billion wild mammals, birds and reptiles have perished. Michael Clarke, an ecologist at La Trobe University in Bundoora, Melbourne, has been studying the effect of fires on native ecosystems — and how they recover — ever since a fire tore through his field site 15 years ago. Clarke spoke to Nature about how animals fare in the wake of wildfires, and why this season’s fires could prove particularly devastating. Last month at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art I saw “2001: A Space Odyssey” on the big screen for my 47th time. The fact that this masterpiece remains on nearly every relevant list of “top ten films” and is shown and discussed over a half-century after its 1968 release is a testament to the cultural achievement of its director Stanley Kubrick, writer Arthur C. Clarke, and their team of expert filmmakers.

Last month at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art I saw “2001: A Space Odyssey” on the big screen for my 47th time. The fact that this masterpiece remains on nearly every relevant list of “top ten films” and is shown and discussed over a half-century after its 1968 release is a testament to the cultural achievement of its director Stanley Kubrick, writer Arthur C. Clarke, and their team of expert filmmakers. Computers can now drive cars, beat world champions at board games like chess and Go, and even write prose. The revolution in artificial intelligence stems in large part from the power of one particular kind of artificial neural network, whose design is inspired by the connected layers of neurons in the mammalian visual cortex. These “convolutional neural networks” (CNNs) have proved surprisingly adept at learning patterns in two-dimensional data — especially in computer vision tasks like recognizing handwritten words and objects in digital images.

Computers can now drive cars, beat world champions at board games like chess and Go, and even write prose. The revolution in artificial intelligence stems in large part from the power of one particular kind of artificial neural network, whose design is inspired by the connected layers of neurons in the mammalian visual cortex. These “convolutional neural networks” (CNNs) have proved surprisingly adept at learning patterns in two-dimensional data — especially in computer vision tasks like recognizing handwritten words and objects in digital images. We are witnessing

We are witnessing  Neiman’s book comprises two parts. The first is dedicated to the historical underpinnings of the German reckoning with Nazism and the Holocaust beginning in the early ’60s, with television broadcasts of the Eichmann and Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, which led a younger generation to ask, for seemingly the first time, about the complacency and complicity of teachers, politicians, and above all fathers. (“Being German in my generation,” the author Carolin Emcke, born in 1967, tells Neiman, “means distrusting yourself.”) Learning from the Germans narrates the subsequent political and cultural evolution, including Willy Brandt’s 1970 Kniefall in penance to the victims of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the Historians Debate of the 1980s, and the 2003–2005 construction of Peter Eisenman’s Holocaust Memorial, a site Neiman dislikes for the vagueness of its abstract form but whose gestation was admittedly long and difficult. Reunification posed a particular set of challenges to how Nazism and the Holocaust were publicly remembered; she contrasts the record of the former East Germany with that of West Germany and largely defends the avowed antifascist state from the charge that it failed to address the German past with anything comparable to Western efforts. Three decades after reunification, the extremist AfD party explicitly frames what it calls a “guilt cult” and threatens the success of the postwar project. Yet no other country (at least in Europe or North America) has made anything like the strides Germany has toward facing the legacy of national evils, whether colonialism in Britain and France or slavery and Jim Crow in America. Only in 2009 did the US Senate approve a resolution apologizing to black Americans for slavery.

Neiman’s book comprises two parts. The first is dedicated to the historical underpinnings of the German reckoning with Nazism and the Holocaust beginning in the early ’60s, with television broadcasts of the Eichmann and Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, which led a younger generation to ask, for seemingly the first time, about the complacency and complicity of teachers, politicians, and above all fathers. (“Being German in my generation,” the author Carolin Emcke, born in 1967, tells Neiman, “means distrusting yourself.”) Learning from the Germans narrates the subsequent political and cultural evolution, including Willy Brandt’s 1970 Kniefall in penance to the victims of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the Historians Debate of the 1980s, and the 2003–2005 construction of Peter Eisenman’s Holocaust Memorial, a site Neiman dislikes for the vagueness of its abstract form but whose gestation was admittedly long and difficult. Reunification posed a particular set of challenges to how Nazism and the Holocaust were publicly remembered; she contrasts the record of the former East Germany with that of West Germany and largely defends the avowed antifascist state from the charge that it failed to address the German past with anything comparable to Western efforts. Three decades after reunification, the extremist AfD party explicitly frames what it calls a “guilt cult” and threatens the success of the postwar project. Yet no other country (at least in Europe or North America) has made anything like the strides Germany has toward facing the legacy of national evils, whether colonialism in Britain and France or slavery and Jim Crow in America. Only in 2009 did the US Senate approve a resolution apologizing to black Americans for slavery. The glamour of both types of horsewoman was impeccable, their skill and bravery vertiginous. These long-dead performers became celebrities to me, fleshed out beyond the Impressionist postcards: Elvira Guerra, the first woman to compete against men at the Olympics in 1900; Caroline Loyo, “the diva of the crop” whose black eyes and disciplinaire riding brought the Jockey Club boys to the Paris circuses; and Suzanne Valadon, the acrobat of Toulouse-Lautrec’s paintings who went on to be an artist herself after an injury cost her her career in the ring.

The glamour of both types of horsewoman was impeccable, their skill and bravery vertiginous. These long-dead performers became celebrities to me, fleshed out beyond the Impressionist postcards: Elvira Guerra, the first woman to compete against men at the Olympics in 1900; Caroline Loyo, “the diva of the crop” whose black eyes and disciplinaire riding brought the Jockey Club boys to the Paris circuses; and Suzanne Valadon, the acrobat of Toulouse-Lautrec’s paintings who went on to be an artist herself after an injury cost her her career in the ring.

WHEN I WAS

WHEN I WAS The thought-provoking Israeli documentary “Advocate,” from the directors Rachel Leah Jones and Philippe Bellaïche, opens with its subject, the human-rights lawyer Lea Tsemel, making her way resolutely toward the elevators at the district court in Tel Aviv. A short and solidly built woman in her seventies, with a mop of dark hair and kohl-rimmed eyes, Tsemel is on her way to the courthouse’s detention cells to meet with a client. “Is it going down?” she asks as she approaches the elevator’s nearly closed doors, before sticking her leg between them and muscling her way in. “Lea, what will become of you? When will you mend your ways?” a man inside the elevator asks her. “Who, me? I’m a lost cause,” she answers.

The thought-provoking Israeli documentary “Advocate,” from the directors Rachel Leah Jones and Philippe Bellaïche, opens with its subject, the human-rights lawyer Lea Tsemel, making her way resolutely toward the elevators at the district court in Tel Aviv. A short and solidly built woman in her seventies, with a mop of dark hair and kohl-rimmed eyes, Tsemel is on her way to the courthouse’s detention cells to meet with a client. “Is it going down?” she asks as she approaches the elevator’s nearly closed doors, before sticking her leg between them and muscling her way in. “Lea, what will become of you? When will you mend your ways?” a man inside the elevator asks her. “Who, me? I’m a lost cause,” she answers. As the full extent of the devastation of the Holocaust became apparent, a Polish Jew whose entire family had been killed,

As the full extent of the devastation of the Holocaust became apparent, a Polish Jew whose entire family had been killed,