Jonathan Wolff in Aeon:

Jonathan Wolff in Aeon:

Ours is the age of the rule by ‘strong men’: leaders who believe that they have been elected to deliver the will of the people. Woe betide anything that stands in the way, be it the political opposition, the courts, the media or brave individuals. While these demonised guardians of freedom are belittled, brushed aside or destroyed, vulnerable groups, such as refugees, immigrants, minorities and those living in poverty, bear the brunt. What can be done to halt or reverse this process? And what will happen if we simply stand by and watch? Some commentators see parallels with the rise of fascism in the 1930s. Others agree that democracy is under threat but suggest that the threats are new. A fair point, but with its dangers. Yes, we must attend to new threats, but old ones can reoccur too.

Stefan Zweig, the Austrian author of Jewish descent, saw his books burnt in university towns across Germany in 1933. His memoirs paint a picture in which everything was normal until it wasn’t. But it would be wrong to think that we can predict how things will turn out. Who foresaw where we are now? The French philosopher Simone Weil, writing in 1934, probably had it right: ‘We are in a period of transition; but a transition towards what? No one has the slightest idea.’

Liberal democratic institutions, such as those we have now, exist only so long as people believe in them. When that belief evaporates, change can be rapid. Beware leaders riding a wave of crude nationalism. Beware democracy submerging into a vague notion of the will of the people. But why now?

More here.

John Cassidy in The New Yorker:

John Cassidy in The New Yorker: Reading “Burn It Down!,” an anthology of feminist manifestos edited by Breanne Fahs, I couldn’t decide whether the book amounted to a celebration or an elegy. In her learned and impassioned introduction, Fahs starts out by enumerating a litany of feminist accomplishments only to pair most of them with their backlash. Federally supported family leave? Typically unpaid. Women’s studies programs? They exist, but they’re dwindling. Abortion access may have expanded worldwide; in the United States, though,

Reading “Burn It Down!,” an anthology of feminist manifestos edited by Breanne Fahs, I couldn’t decide whether the book amounted to a celebration or an elegy. In her learned and impassioned introduction, Fahs starts out by enumerating a litany of feminist accomplishments only to pair most of them with their backlash. Federally supported family leave? Typically unpaid. Women’s studies programs? They exist, but they’re dwindling. Abortion access may have expanded worldwide; in the United States, though,

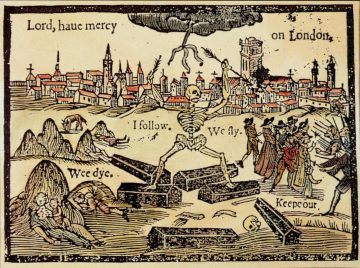

Toward the end of January, I began to notice a strange echo between my work and the news. A mysterious virus had appeared in the city of Wuhan, and though the virus resembled previous diseases, there was something novel about it. But I’m not a doctor, an epidemiologist or a public health expert; I’m a literary translator. Usually my work moves more slowly than the events of the moment, since translation involves lingering over the patterns of a sentence or the connotations of a word. But this time the pace of my work and the pace of the virus were eerily similar. That’s because I’m translating Albert Camus’s novel “The Plague.”

Toward the end of January, I began to notice a strange echo between my work and the news. A mysterious virus had appeared in the city of Wuhan, and though the virus resembled previous diseases, there was something novel about it. But I’m not a doctor, an epidemiologist or a public health expert; I’m a literary translator. Usually my work moves more slowly than the events of the moment, since translation involves lingering over the patterns of a sentence or the connotations of a word. But this time the pace of my work and the pace of the virus were eerily similar. That’s because I’m translating Albert Camus’s novel “The Plague.” Impotence and incontinence are common side effects of treatment for prostate cancer. For men with aggressive forms of the disease, these treatment consequences will outweigh the alternative — prostate cancer is one of the biggest cancer killers in men. But a large proportion of people diagnosed with prostate cancer are treated for slow-growing tumours that would have been unlikely to cause harm if left alone — the potential side effects of treatment overshadow the gains. These people are treated because their cancers are flagged by screening programmes. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment are also common outcomes of breast-cancer screening, leading researchers to question whether screening for these cancers is doing more harm than good.

Impotence and incontinence are common side effects of treatment for prostate cancer. For men with aggressive forms of the disease, these treatment consequences will outweigh the alternative — prostate cancer is one of the biggest cancer killers in men. But a large proportion of people diagnosed with prostate cancer are treated for slow-growing tumours that would have been unlikely to cause harm if left alone — the potential side effects of treatment overshadow the gains. These people are treated because their cancers are flagged by screening programmes. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment are also common outcomes of breast-cancer screening, leading researchers to question whether screening for these cancers is doing more harm than good. How is the state supposed to deal with the economic consequences of a lockdown? What happens if supply chains break down? How are daily wagers supposed to feed themselves in the absence of economic activity? What happens if social order breaks down?

How is the state supposed to deal with the economic consequences of a lockdown? What happens if supply chains break down? How are daily wagers supposed to feed themselves in the absence of economic activity? What happens if social order breaks down? As I wrote

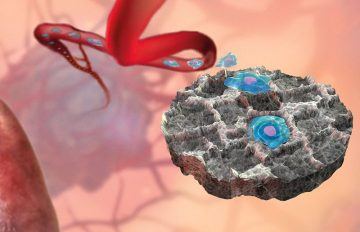

As I wrote An animal study has shown that implanting a tiny, cell-attracting scaffold below the skin can help physicians to track cancer progression, potentially reducing the need for tissue biopsy. Researchers have observed that before malignant tumours spread from their primary location to other parts of the body, they deploy circulating tumour molecules that suppress the body’s immune response — a strategy that makes it easier for the cancer to infiltrate distant organs. Bioengineer Lonnie Shea at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and his team developed a scaffold that could detect and trap circulating immune and cancer cells during the period before a cancer spreads.

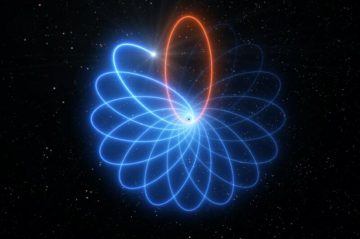

An animal study has shown that implanting a tiny, cell-attracting scaffold below the skin can help physicians to track cancer progression, potentially reducing the need for tissue biopsy. Researchers have observed that before malignant tumours spread from their primary location to other parts of the body, they deploy circulating tumour molecules that suppress the body’s immune response — a strategy that makes it easier for the cancer to infiltrate distant organs. Bioengineer Lonnie Shea at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and his team developed a scaffold that could detect and trap circulating immune and cancer cells during the period before a cancer spreads. It’s been nearly 30 years in the making, but scientists with the Very Large Telescope (VLT) collaboration in the Atacama Desert in Chile have now measured, for the very first time, the unique orbit of a star orbiting the supermassive black hole believed to lie at the center of our Milky Way galaxy. The path of the star (known as S2) traces a distinctive rosette-shaped pattern (similar to a spirograph), in keeping with one of the central predictions of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity. The international collaboration described their results

It’s been nearly 30 years in the making, but scientists with the Very Large Telescope (VLT) collaboration in the Atacama Desert in Chile have now measured, for the very first time, the unique orbit of a star orbiting the supermassive black hole believed to lie at the center of our Milky Way galaxy. The path of the star (known as S2) traces a distinctive rosette-shaped pattern (similar to a spirograph), in keeping with one of the central predictions of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity. The international collaboration described their results  Many religious people see something benevolent in nature, or at least see purpose dimly grasped in the interworking of biology. But there’s something even deeper than religious optimism. There is a broader conception of nature — shared by monotheists, polytheists, Indigenous animists, and now politicians and policymakers. It is the mythopoetic view of nature. It is the universal instinct to find (or project) a plot in nature. A mythopoetic paradigm or perspective sees the world primarily as a dramatic story of competing personal intentions, rather than a system of objective, impersonal laws. It’s a prescientific worldview, but it is also alive and well in the contemporary mind.

Many religious people see something benevolent in nature, or at least see purpose dimly grasped in the interworking of biology. But there’s something even deeper than religious optimism. There is a broader conception of nature — shared by monotheists, polytheists, Indigenous animists, and now politicians and policymakers. It is the mythopoetic view of nature. It is the universal instinct to find (or project) a plot in nature. A mythopoetic paradigm or perspective sees the world primarily as a dramatic story of competing personal intentions, rather than a system of objective, impersonal laws. It’s a prescientific worldview, but it is also alive and well in the contemporary mind. Heinrich von Kleist died by his own hand at the age of thirty-four. For a man whose life was plagued by failure, his suicide was a remarkable success. On November 20, 1811, two months after turning his eighth play over to the Prussian censors, Kleist and his friend Henriette Vogel retired to an inn outside Berlin, where for one night and one day they sang and prayed, composed final letters, and downed bottles of rum and wine (as well as, the London Times later reported, sixteen cups of coffee) before making their way to the banks of the Kleiner Wannsee. In these idyllic surroundings, as per their agreement, Kleist shot her in the chest, reloaded, and then fired at his own head. “I am blissfully happy,” he had written to his cousin that morning. “Now I can thank [God] for my life, the most tortured ever lived by any human being, since He makes it up to me with this most splendid and pleasurable of deaths.”

Heinrich von Kleist died by his own hand at the age of thirty-four. For a man whose life was plagued by failure, his suicide was a remarkable success. On November 20, 1811, two months after turning his eighth play over to the Prussian censors, Kleist and his friend Henriette Vogel retired to an inn outside Berlin, where for one night and one day they sang and prayed, composed final letters, and downed bottles of rum and wine (as well as, the London Times later reported, sixteen cups of coffee) before making their way to the banks of the Kleiner Wannsee. In these idyllic surroundings, as per their agreement, Kleist shot her in the chest, reloaded, and then fired at his own head. “I am blissfully happy,” he had written to his cousin that morning. “Now I can thank [God] for my life, the most tortured ever lived by any human being, since He makes it up to me with this most splendid and pleasurable of deaths.” Rainey and Smith, along with fellow blueswoman Lucille Bogan, set the stage for pop music’s tendency to incubate androgyny, queerness, and other taboos in plain view of the powers that would seek to snuff them out. They were joined by Gladys Bentley, the stone butch blues singer who performed in a top hat and tails throughout the Harlem Renaissance in New York and whose deep, gritty voice foreshadowed the guttural howls of rock stars.

Rainey and Smith, along with fellow blueswoman Lucille Bogan, set the stage for pop music’s tendency to incubate androgyny, queerness, and other taboos in plain view of the powers that would seek to snuff them out. They were joined by Gladys Bentley, the stone butch blues singer who performed in a top hat and tails throughout the Harlem Renaissance in New York and whose deep, gritty voice foreshadowed the guttural howls of rock stars. A lot has been written about how this pandemic is exacerbating social inequalities. But what if it’s because our societies are so unequal that this pandemic happened?

A lot has been written about how this pandemic is exacerbating social inequalities. But what if it’s because our societies are so unequal that this pandemic happened? It’s hard doing science when you only have one data point, especially when that data point is subject to an enormous selection bias. That’s the situation faced by people studying the nature and prevalence of life in the universe. The only biosphere we know about is our own, and our knowing anything at all is predicated on its existence, so it’s unclear how much it can teach us about the bigger picture. That’s why it’s so important to search for life elsewhere. Today’s guest is Kevin Hand, a planetary scientist and astrobiologist who knows as much as anyone about the prospects for finding life right in our planetary backyard, on moons and planets in the Solar System. We talk about how life comes to be, and reasons why it might be lurking on Europa, Titan, or elsewhere.

It’s hard doing science when you only have one data point, especially when that data point is subject to an enormous selection bias. That’s the situation faced by people studying the nature and prevalence of life in the universe. The only biosphere we know about is our own, and our knowing anything at all is predicated on its existence, so it’s unclear how much it can teach us about the bigger picture. That’s why it’s so important to search for life elsewhere. Today’s guest is Kevin Hand, a planetary scientist and astrobiologist who knows as much as anyone about the prospects for finding life right in our planetary backyard, on moons and planets in the Solar System. We talk about how life comes to be, and reasons why it might be lurking on Europa, Titan, or elsewhere.