Category: Archives

Tuesday Poem

Brown Small Bird

The Nightingale will always be a mythical bird.

Did you ever see one outside poetry?

The Nightingale is named into anonymity, like a Monk,

like the celebrated girl who is only beautiful.

What a different thing it was when

Wild-Bird took

actual berries from my hand.

Blessed, I wanted statues made of it, a

city named, or something

Brown, small, bird.

Not to be known by his name anymore

than you, or me

by Lew Welsh

from Ring of Bone

Grey Fox Press,1979

Sunday, February 18, 2024

Thirteen Ways of Looking at Art

William Deresiewicz in Salmagundi:

Art is useless, said Wilde. Art is for art’s sake—that is, for beauty’s sake. But why do we possess a sense of beauty to begin with? A question we will never answer. Perhaps it’s just a kind of superfluity of sexual attraction. Nature needs us to feel drawn to other human bodies, but evolution is imprecise. In order to go far enough, to make that feeling strong enough, it went too far. Others are powerfully lovely to us, but so, in a strangely different, strangely similar way, are flowers and sunsets. Art, in turn, this line of thought might go, is a response to natural beauty. Stunned by it, we seek to rival it, to reproduce it, to prolong it. Flowers fade, sunsets melt from moment to moment; the love of bodies brings us grief. Art abides. “When old age shall this generational waste, / Thou shalt remain.”

Art is useless, said Wilde. Art is for art’s sake—that is, for beauty’s sake. But why do we possess a sense of beauty to begin with? A question we will never answer. Perhaps it’s just a kind of superfluity of sexual attraction. Nature needs us to feel drawn to other human bodies, but evolution is imprecise. In order to go far enough, to make that feeling strong enough, it went too far. Others are powerfully lovely to us, but so, in a strangely different, strangely similar way, are flowers and sunsets. Art, in turn, this line of thought might go, is a response to natural beauty. Stunned by it, we seek to rival it, to reproduce it, to prolong it. Flowers fade, sunsets melt from moment to moment; the love of bodies brings us grief. Art abides. “When old age shall this generational waste, / Thou shalt remain.”

Art is for truth. Even Wilde suggests as much, though he, and we, don’t call it truth but meaning. Art points beyond itself. At what? At us. The role of art is to compile the endless atlas of human experience. It’s often not a pretty picture for, as Solzhenitsyn said, the line between good and evil runs through every human heart. Except it’s not a line; it’s a tangle. The gurus want to solve human nature; so do the utopians, the ideologues and revolutionaries. The artist, wiser, observes it, above all in herself.

More here.

Ella Fitzgerald & Louis Armstrong – The Nearness Of You

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2024 theme of “African Americans and the Arts” throughout the month of February)

Hatred Alone Is Immortal

Alan Jacobs in The Hedgehog Review:

Many Americans, as far as I can tell, don’t want to shape their views in accordance with the data; many Americans, again as far as I can tell, don’t want to create an environment in which a broad range of perspectives are freely articulated and peacefully debated. They don’t want to be hopeful about the possibilities of America. Nor do they want academic freedom in our universities. What many people want, what they earnestly and passionately desire, is to hate their enemies. A few years ago J.D. Vance—now a senator, then a political neophyte—uttered The Creed of Our Age: “I think our people hate the right people.”

Many Americans, as far as I can tell, don’t want to shape their views in accordance with the data; many Americans, again as far as I can tell, don’t want to create an environment in which a broad range of perspectives are freely articulated and peacefully debated. They don’t want to be hopeful about the possibilities of America. Nor do they want academic freedom in our universities. What many people want, what they earnestly and passionately desire, is to hate their enemies. A few years ago J.D. Vance—now a senator, then a political neophyte—uttered The Creed of Our Age: “I think our people hate the right people.”

And that’s why the essential text for our time is an essay written almost exactly two hundred years ago by the English writer William Hazlitt: “On the Pleasure of Hating.”

More here.

Highly repetitive regions of junk DNA may be the key to a newly discovered mechanism for gene regulation

Philip Ball in Quanta:

Initially, it was suspected that gene regulation was a simple matter of one gene product acting as an on/off switch for another gene, in digital fashion. In the 1960s, the French biologists François Jacob and Jacques Monod first elucidated a gene regulatory process in mechanistic detail: In Escherichia coli bacteria, when a repressor protein binds to a certain segment of DNA, it blocks the transcription and translation of an adjacent suite of genes that encode enzymes for digesting the sugar lactose. This regulatory circuit, which Monod and Jacob dubbed the lac operon, has a neat, transparent logic.

Initially, it was suspected that gene regulation was a simple matter of one gene product acting as an on/off switch for another gene, in digital fashion. In the 1960s, the French biologists François Jacob and Jacques Monod first elucidated a gene regulatory process in mechanistic detail: In Escherichia coli bacteria, when a repressor protein binds to a certain segment of DNA, it blocks the transcription and translation of an adjacent suite of genes that encode enzymes for digesting the sugar lactose. This regulatory circuit, which Monod and Jacob dubbed the lac operon, has a neat, transparent logic.

But gene regulation in complex metazoans — animals like humans, with complex eukaryotic cells — doesn’t generally seem to work this way. Instead, it involves a gang of molecules, including proteins, RNAs and pieces of DNA from throughout a chromosome, that somehow collaborate to control the expression of a gene.

More here.

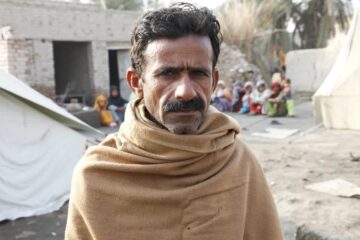

Pakistan needs a plan

Noah Smith at Noahpinion:

Pakistan is a vast country of 231.4 million people. It’s one of only nine countries in the world with nuclear weapons. It’s located in South Asia, which is now one of the world’s most dynamic and fast-growing regions. It has generally favorable relationships with both the United States and China. It has a long coastline in a generally peaceful region of the ocean. It has plenty of talented people, as evidenced by the fact that Pakistani Americans, on average, out-earn almost all other ethnic groups in the U.S.

Pakistan is a vast country of 231.4 million people. It’s one of only nine countries in the world with nuclear weapons. It’s located in South Asia, which is now one of the world’s most dynamic and fast-growing regions. It has generally favorable relationships with both the United States and China. It has a long coastline in a generally peaceful region of the ocean. It has plenty of talented people, as evidenced by the fact that Pakistani Americans, on average, out-earn almost all other ethnic groups in the U.S.

And yet despite these natural advantages, Pakistan is one of the world’s biggest economic basket cases. It’s a poor country, and its income is growing only very slowly; it has now been passed up by India and Bangladesh, despite starting out significantly richer…

More here.

Frontier AI ethics

Seth Lazar in Aeon:

Much of the attention being paid to generative AI systems has focused on how they replicate the pathologies of already widely deployed AI systems, arguing that they centralise power and wealth, ignore copyright protections, depend on exploitative labour practices, and use excessive resources. Other critics highlight how they foreshadow vastly more powerful future systems that might threaten humanity’s survival. The first group says there is nothing new here; the other looks through the present to a perhaps distant horizon.

Much of the attention being paid to generative AI systems has focused on how they replicate the pathologies of already widely deployed AI systems, arguing that they centralise power and wealth, ignore copyright protections, depend on exploitative labour practices, and use excessive resources. Other critics highlight how they foreshadow vastly more powerful future systems that might threaten humanity’s survival. The first group says there is nothing new here; the other looks through the present to a perhaps distant horizon.

I want instead to pay attention to what makes these particular systems distinctive: both their remarkable scientific achievement, and the most likely and consequential ways in which they will change society over the next five to 10 years.

More here.

Cecilia Gentili (1972 – 2024) Transgender Activist, Performer, and Author

Wilhelmenia Wiggins Fernandez (1949 – 2024) Diva

Sunday Poem

Wind and Water and Stone

—for Roger Caillois

The water hollowed the stone,

the wind dispersed the water,

the stone stopped the wind.

Water and wind and stone.

The wind sculpted the stone,

the stone is a cup of water,

the water runs off and is wind.

Stone and wind and water.

The wind sings in its turnings,

the water murmurs as it goes,

the motionless stone is quiet.

Wind and water and stone.

One is the other, and is neither:

among their empty names

they pass and disappear,

water and stone and wind.

by Oactavio Paz

from The Collected Poems 1957-1987

Carcanet Press Limited, 1988

Saturday, February 17, 2024

The Campaign to Abolish UNRWA

Peter Beinart in Jewish Currents:

THE UNITED NATIONS RELIEF AND WORKS AGENCY (UNRWA), which has provided education, health care, and other essential services to Palestinian refugees since 1949, could soon disappear. In recent weeks, the United States and at least 18 other countries have suspended aid to the agency, which operates in the Gaza Strip as well as the West Bank, East Jerusalem, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria, serving more than five million people. The House and Senate are both considering legislation to prevent the US—which is UNRWA’s largest donor—from ever resuming that funding. UNRWA officials have said that if funding is not restored, the organization will likely halt operations as early as the end of this month.

The current effort to abolish UNRWA dates from late January, when Israel alleged that 12 of the agency’s staff members took part in the October 7th massacre, and that roughly 1200 employees—10% of UNRWA’s workforce in Gaza—have ties to Hamas or other militant groups. But Israel and its supporters in the US have been seeking to undermine the agency for at least a decade. In 2018, when leaked emails revealed that then-President Donald Trump’s son-in-law and senior advisor Jared Kushner was attempting to “disrupt UNRWA” because the agency “perpetuates a status quo” and “is corrupt, inefficient and doesn’t help peace,” a number of mainstream Jewish groups praised Kushner’s efforts. The Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations declared that UNRWA “is not the answer” to Palestinians’ humanitarian needs. (The Trump administration later cut off US aid to UNRWA; Joe Biden restored the funding soon after entering office.) In 2021, Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations, Gilad Erdan, urged that “this UN agency for so-called ‘refugees’ should not exist in its current format.”

More here.

Rafah May Prove the Most Dire Moment in Israel’s War on Gaza

Sarah Burch in Jacobin:

On Sunday, while one hundred million Americans were watching the kickoff of the Super Bowl, Israel took the opportunity to unleash the next stage in its genocide of Palestinians. Air strikes over Rafah killed at least sixty-seven Palestinians, while Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu ordered soldiers to prepare for a ground entry into the city.

Rafah, on Gaza’s southern border with Egypt, is the last refuge for nearly 1.5 million Palestinians displaced by the ongoing Israeli genocide.

Since Israeli bombs began decimating Northern Gaza in October, Palestinians have been told to evacuate to the south. Rafah is as far south as anyone can go. With a ground invasion imminent, the Israeli government is calling for the population to “evacuate” — even though they have nowhere to evacuate to.

An Israeli invasion of Rafah would be the most dangerous stage of the genocide yet, causing death on a scale unseen even in these four months of sheer brutality.

After indiscriminately flattening Gaza and pushing Palestinians toward famine, now the Israeli military is seeking to remove the Palestinians from Gaza permanently, whether by displacement, disease, hunger, or execution.

More here.

Is the State Here to Stay?

Jonathan S. Blake in Boston Review:

In early 2022, the Economist decried “governments’ widespread new fondness for interventionism.” The state was “becoming bossier” and “more meddlesome,” it complained. In fact, the state’s punitive arm was plenty active in the United States and the United Kingdom during the decades that neoliberalism shredded public investment and public goods, to say nothing of the foreign interventions of these states over this period. But on the economic front, at least, the Economist was right: state spending and regulation are back after years of retrenchment.

In the United States, the federal government has recently spent $5 trillion under two presidents to act against public health and economic threats, and the Biden administration is boastfully pursuing “industrial policy” to remedy problems created by four decades of deference to the private sector, especially around climate. Add to this a more aggressive approach to antitrust enforcement and regulation in general, and the administrative and development elements of today’s American state looks very different than they did in 1990 or even 2010. This new statism is a direct response to the rise of China as well as a rejection of the anemic policies rolled out to combat the 2008 financial crisis. Many left-of-center officials and policy intellectuals have concluded that both national security and the preservation of democracy against populist threats require more vigorous government control over markets.

More here.

How Quickly Do Large Language Models Learn Unexpected Skills?

Stephen Ornes in Quanta:

Two years ago, in a project called the Beyond the Imitation Game benchmark, or BIG-bench, 450 researchers compiled a list of 204 tasks designed to test the capabilities of large language models, which power chatbots like ChatGPT. On most tasks, performance improved predictably and smoothly as the models scaled up — the larger the model, the better it got. But with other tasks, the jump in ability wasn’t smooth. The performance remained near zero for a while, then performance jumped. Other studies found similar leaps in ability.

The authors described this as “breakthrough” behavior; other researchers have likened it to a phase transition in physics, like when liquid water freezes into ice. In a paper published in August 2022, researchers noted that these behaviors are not only surprising but unpredictable, and that they should inform the evolving conversations around AI safety, potential and risk. They called the abilities “emergent,” a word that describes collective behaviors that only appear once a system reaches a high level of complexity.

But things may not be so simple. A new paper by a trio of researchers at Stanford University posits that the sudden appearance of these abilities is just a consequence of the way researchers measure the LLM’s performance. The abilities, they argue, are neither unpredictable nor sudden.

More here.

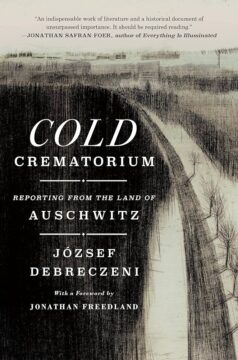

Reporting From The Land Of Auschwitz

Joe Moshenska at The Guardian:

József Debreczeni’s memoir of the Nazi death camps, translated into English from Hungarian for the first time, frequently echoes Edgar’s claim. After being moved from “the capital of the Great Land of Auschwitz” to one of the networks of sub-camps, Eule, he discovers that he is to be moved again: “Surely I couldn’t end up in a place much worse, I thought – and how tragically wrong I was.” By the end of his remarkable set of observational writings, the word “worse” has lost all meaning; comparing the depths of human experiences of depravity and suffering feels obscene in itself. Is typhoid worse than starvation? Is being crushed to death while mining a subterranean tunnel worse than wasting away in a pool of one’s own filth?

József Debreczeni’s memoir of the Nazi death camps, translated into English from Hungarian for the first time, frequently echoes Edgar’s claim. After being moved from “the capital of the Great Land of Auschwitz” to one of the networks of sub-camps, Eule, he discovers that he is to be moved again: “Surely I couldn’t end up in a place much worse, I thought – and how tragically wrong I was.” By the end of his remarkable set of observational writings, the word “worse” has lost all meaning; comparing the depths of human experiences of depravity and suffering feels obscene in itself. Is typhoid worse than starvation? Is being crushed to death while mining a subterranean tunnel worse than wasting away in a pool of one’s own filth?

Debreczeni, an eminent journalist, thwarts any such comparisons by allowing the events that unfold to hover before the reader in the astonishing equipoise of his prose.

more here.

Filming ‘Virginia Woolf,’ the Battles Weren’t Just Onscreen

Alexandra Jacobs at the New York Times:

What a document dump!

What a document dump!

The most delicious parts of “Cocktails With George and Martha,” Philip Gefter’s unapologetically obsessive new book about “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” — the dark ’n’ stormy, oft-revived 1962 Broadway hit by Edward Albee that became a moneymaking movie and an eternal marriage meme — are diary excerpts from the screenwriter Ernest Lehman. (Gefter calls the diary “unpublished,” but at least some of it surfaced in the turn-of-the-millennium magazine Talk, now hard to find.)

That Lehman is no longer a household name, if he ever was, is one of showbiz history’s many injustices. Before the thankless task of condensing Albee’s three-hour play for the big screen (on top of producing), he wrote the scripts for “North by Northwest” (1959), arguably Hitchcock’s greatest, and with some help, “Sweet Smell of Success” (1957).

more here.

Philip Gefter with Lynne Tillman

Saturday Poem

Pelicans

Don’t fool yourself: you don’t know anything

about birds. So you’ve seen a documentary,

skimmed a book, can tell robins from chickadees.

You’ve stared across canyons, been pushed off a fence,

can guess what soaring is—falling in reverse—

but have you ever looked at a pelican?

Their beauty’s folded awkwardness, red

lidless eyes, mouths baggy as inflatable pants.

Their webbed feet push the brakes mid-air,

like cartoon ducks’. No cormorants,

no sleek-arrow hunters, they wheel above the surf

and drop like a stack of twenty pancakes,

gulp at foam and fish, then struggle to

take off again. Drying out on shore, they

wonder what they’ve done to deserve

such graceful wings.

You should wish to be so brainless,

inefficient, beautiful. You drove past

them once, on your way to catch a plane.

Flying alone, no longer among them,

you’ve returned to knowing nothing

about birds, or who you are. Just eyeing

other people, wondering what you’ve done

to deserve this life. Your only one.

by Derek Webster

from Mockingbird

Véhicule Press, 2015

Where Western and Indian philosophy meet

Chakravarthi Ram-Prasad in IAI:

We find similar ideas of a transcendent ego in both Kant and the Upanishads. We find a rejection of free will in Schopenhauer and Ramana Maharshi. What should we make of this overlap between Western and Indian philosophy? Chakravarthi Ram-Prasad argues both became gripped by the same question.

We find similar ideas of a transcendent ego in both Kant and the Upanishads. We find a rejection of free will in Schopenhauer and Ramana Maharshi. What should we make of this overlap between Western and Indian philosophy? Chakravarthi Ram-Prasad argues both became gripped by the same question.

Ricky Williamson: What do you think are the key differences and similarities between Western and Indian philosophy?

Chakravarthi Ram-Prasad: I don’t think that there is actually a global answer to the question of differences between what are, broadly speaking, historically constructed traditions. While we might intuitively think we recognise what Western philosophy is or what Indian philosophy is, in practice it’s more complicated.

A particularly potent example of the difficulty is the question of whether Arabic philosophy counts as Western philosophy. We know that the whole Aristotelian tradition was lost to the Latin-writing European philosophical tradition and was preserved by the Arabs and in Arabic. It only returned to the European tradition in the Renaissance, which launched a whole series of rediscoveries of Greek materials. Some people have therefore argued that Arabic philosophy is part of Western philosophy. But others would point out that within Islamic thought, as it was articulated in Arabic, Persian or Turkish, there was such a thing as Falsafah, which was a particular branch of philosophy and which was integrated into questions that were doctrinally based on Islamic revelation. So, they would conclude, of course what we might call Arabic philosophy is nothing like Western philosophy.

More here.