Liz Fields on PBS:

The mesmerizing performance from Academy Award-nominated actress and singer Andra Day in “The United States Vs. Billie Holiday” has revived interest in the hauntingly beautiful and controversial song “Strange Fruit,” which Holiday first popularized in the late 1930s. The film details the numerous ways in which the US government terrorized the singer over her performances of the song right up until her untimely death in 1959, but it does not cover the unusual origins of the song, which was originally written as a poem by a Jewish American teacher from the Bronx, who was also a member of the Communist party.

The mesmerizing performance from Academy Award-nominated actress and singer Andra Day in “The United States Vs. Billie Holiday” has revived interest in the hauntingly beautiful and controversial song “Strange Fruit,” which Holiday first popularized in the late 1930s. The film details the numerous ways in which the US government terrorized the singer over her performances of the song right up until her untimely death in 1959, but it does not cover the unusual origins of the song, which was originally written as a poem by a Jewish American teacher from the Bronx, who was also a member of the Communist party.

Abel Meeropol, a son of Russian Jewish immigrants, taught English at Dewitt Clinton High School in the Bronx for 17 years before turning to music and motion pictures, writing under the pen name Lewis Allan. Meeropol was very disturbed by the persistence of systemic racism in America and was motivated to write the poem “Bitter Fruit” after seeing a photo depicting the lynching of two Black teens in Indiana in 1930. The poem was published in the journal The New York Teacher in 1937, and again later published in the Marxist journal, The New Masses, before Meeropol decided to turn the poem into lyrics and set it to music.

After that, Meeropol began to perform the song at several protest rallies and venues around the city along with his wife and African American singer Laura Duncan. The song first came to Holiday’s attention when she was working at New York’s first integrated nightclub, Café Society in Greenwich Village. Holiday was hesitant at first to sing it because she didn’t want to politicize her performances, and was (rightfully) concerned about being targeted at her performances. But the positive audience responses and frequent requests for “Strange Fruit” soon prompted Holiday to close out every performance with the song. Ahead of time, the waiters would stop serving so there was a deathly silence in the room, then a spotlight would shine on Holiday’s face and she would begin to sing:

“Southern trees bear a strange fruit/ Blood on the leaves and blood at the root/ Black bodies swingin’ in the Southern breeze/ Strange fruit hangin’ from the poplar trees…”

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2024 theme of “African Americans and the Arts” throughout the month of February)

Panpsychism is the view that consciousness is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of the physical world. It is the view that the basic building blocks of the physical universe – perhaps fundamental particles – have incredibly simple forms of experience, and that the very sophisticated experience of the human or animal brain is rooted in, derived from, more rudimentary forms of experience at the level of basic physics. Panpsychism has received a lot of attention of late. The world of academic philosophy has been rocked by the conversion of one of the most influential materialists of the last thirty years, Michael Tye, to a form of panpsychism (

Panpsychism is the view that consciousness is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of the physical world. It is the view that the basic building blocks of the physical universe – perhaps fundamental particles – have incredibly simple forms of experience, and that the very sophisticated experience of the human or animal brain is rooted in, derived from, more rudimentary forms of experience at the level of basic physics. Panpsychism has received a lot of attention of late. The world of academic philosophy has been rocked by the conversion of one of the most influential materialists of the last thirty years, Michael Tye, to a form of panpsychism ( Throughout cinematic history, legendary Black actors have shattered barriers and

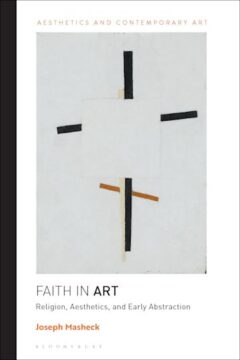

Throughout cinematic history, legendary Black actors have shattered barriers and  In the end, Faith in Art offers neither comprehensive views of these artists nor definitive conclusions about the religious bearings of their work. Nor is it concerned with establishing these artists’ faithful (or unfaithful) adherence to particular religious traditions—indeed, “none was religious in any conspicuous way.” Rather, Masheck seeks to show how “they believed that art had something formative to say about the possibility of a new, more humane society, by a faith ultimately based on scriptural, and sometimes surprisingly theological, intellectual formations.” This effectively pries open the critical histories of these artists, such that reducing these formations to either “materialism” or “spiritualism” becomes untenable.

In the end, Faith in Art offers neither comprehensive views of these artists nor definitive conclusions about the religious bearings of their work. Nor is it concerned with establishing these artists’ faithful (or unfaithful) adherence to particular religious traditions—indeed, “none was religious in any conspicuous way.” Rather, Masheck seeks to show how “they believed that art had something formative to say about the possibility of a new, more humane society, by a faith ultimately based on scriptural, and sometimes surprisingly theological, intellectual formations.” This effectively pries open the critical histories of these artists, such that reducing these formations to either “materialism” or “spiritualism” becomes untenable.

Evolution is sometimes described — not precisely, but with some justification — as being about the “survival of the fittest.” But that idea doesn’t work unless there is some way for one generation to pass down information about how best to survive. We now know that such information is passed down in a variety of ways: through our inherited genome, through epigenetic factors, and of course through cultural transmission. Chris Adami suggests that we update Dobzhansky’s maxim “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution” to “… except in the light of information.” We talk about information theory as a subject in its own right, and how it helps us to understand organisms, evolution, and the origin of life.

Evolution is sometimes described — not precisely, but with some justification — as being about the “survival of the fittest.” But that idea doesn’t work unless there is some way for one generation to pass down information about how best to survive. We now know that such information is passed down in a variety of ways: through our inherited genome, through epigenetic factors, and of course through cultural transmission. Chris Adami suggests that we update Dobzhansky’s maxim “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution” to “… except in the light of information.” We talk about information theory as a subject in its own right, and how it helps us to understand organisms, evolution, and the origin of life. Just days before October 7, President Joe Biden’s national security advisor, Jake Sullivan, was radiating confidence that Washington had effectively brought all of West Asia’s long-roiling conflicts under control. Washington could now, he believed, accelerate the pivot of attention, forces, and funding toward what had long topped Biden’s agenda: containing Chinese power in East Asia. Then came the Hamas-led attack on Israel and Israel’s onslaught on Gaza. By late January, Sullivan was flying to Bangkok to plead with top Chinese diplomat Wang Yi for help in defusing the sharp, Gaza-spurred conflict that had erupted in the globally vital waterway of the Red Sea. (Wang politely blew him off.)

Just days before October 7, President Joe Biden’s national security advisor, Jake Sullivan, was radiating confidence that Washington had effectively brought all of West Asia’s long-roiling conflicts under control. Washington could now, he believed, accelerate the pivot of attention, forces, and funding toward what had long topped Biden’s agenda: containing Chinese power in East Asia. Then came the Hamas-led attack on Israel and Israel’s onslaught on Gaza. By late January, Sullivan was flying to Bangkok to plead with top Chinese diplomat Wang Yi for help in defusing the sharp, Gaza-spurred conflict that had erupted in the globally vital waterway of the Red Sea. (Wang politely blew him off.) E

E The Oscars have never been about art. As Louis B. Mayer

The Oscars have never been about art. As Louis B. Mayer  The field of biology has driven remarkable advancements in medicine, agriculture, and industry over the last half-century, despite facing a significant hurdle: The immense complexity of biological systems makes them incredibly difficult to predict. This lack of predictability means that any innovation in biology requires many expensive trial-and-error experiments, inflating costs and slowing down progress in a wide range of applications, from drug discovery to biomanufacturing. But we are now at a critical inflection point in our ability to predict and engineer complex biological systems—transforming biology from a wet and messy science into an engineering discipline. This is being driven by the convergence of three major innovations: advancements in deep learning, significant cost reductions for collecting biological data through lab automation, and the precision editing of DNA with CRISPR.

The field of biology has driven remarkable advancements in medicine, agriculture, and industry over the last half-century, despite facing a significant hurdle: The immense complexity of biological systems makes them incredibly difficult to predict. This lack of predictability means that any innovation in biology requires many expensive trial-and-error experiments, inflating costs and slowing down progress in a wide range of applications, from drug discovery to biomanufacturing. But we are now at a critical inflection point in our ability to predict and engineer complex biological systems—transforming biology from a wet and messy science into an engineering discipline. This is being driven by the convergence of three major innovations: advancements in deep learning, significant cost reductions for collecting biological data through lab automation, and the precision editing of DNA with CRISPR.

Maya Angelou

Maya Angelou T

T