A Pile of Fish

—for Paul Otremba

Six in all, to be exact. I know it was a Tuesday

or Wednesday because the museum closes early

on those days. I almost wrote something

about the light being late—; the “late light”

is what I almost said, and you know how we

poets go on and on about the light and

the wind and the dark, but that day the dark was still

far away swimming in the Pacific, and we had

45 minutes to find Goya’s “Still Life with Bream”

before the doors closed. I’ve now forgotten

three times the word Golden in the title of that painting

—and I wish I could ask what you think

that means. I see that color most often

these days when the cold, wet light of morning

soaks my son’s curls and his already light

brown hair takes on the flash of fish fins

in moonlight. I read somewhere

that Goya never titled this painting,

or the other eleven still lifes, so it’s just

as well because I like the Spanish title better.

“Doradas” is simple, doesn’t point

out the obvious. Lately, I’ve been saying

dorado so often in the song I sing

to my son, “O sol, sol, dorado sol

no te escondes…” I felt lost

that day in the museum, but you knew

where we were going having been there

so many times. The canvas was so small

at 17 x 24 inches. I stood before it

lost in its beach of green sand and

that silver surf cut with pink.

I stared while you circled the room

like a curious cat. I took a step back,

and then with your hands in your pockets

you said, No matter where we stand,

there’s always one fish staring at us.

As a new father, I am now that pyramid

of fish; my body is all eyes and eyes.

Some of them watch for you in the west

where the lion sun yawns and shakes off

its sleep before it purrs, and hungry,

dives deep in the deep of the deep.

by Tomás Q. Morín

from the Academy of American Poets

There are as many as 9 million feral swine across the U.S., their populations having expanded from about 17 states to 38 over the last three decades. Canada doesn’t have comparable data, but Ryan Brook, a University of Saskatchewan biologist who researches wild pigs, predicts that they will occupy 386,000 square miles across the country by the end of 2020, and they’re currently expanding at about 35,000 square miles a year.

There are as many as 9 million feral swine across the U.S., their populations having expanded from about 17 states to 38 over the last three decades. Canada doesn’t have comparable data, but Ryan Brook, a University of Saskatchewan biologist who researches wild pigs, predicts that they will occupy 386,000 square miles across the country by the end of 2020, and they’re currently expanding at about 35,000 square miles a year.

For good reason, The Great Gatsby is one of the most admired and talked-about books of the twentieth century. And that reason is, of course, that it’s really short—47,094 words, to be exact. I read it for the first time in a few hours at a swim meet (the aptness of the setting wasn’t clear to me until Chapter 8) and probably would have finished sooner had it not been for the snatches of Eminem coming from somebody’s boombox. You can count the book’s speaking roles on your fingers, and any high school sophomore can skim it the night before the big exam. Assign that to millions of teenagers for sixty-odd years, and a Great American Novel is born.

For good reason, The Great Gatsby is one of the most admired and talked-about books of the twentieth century. And that reason is, of course, that it’s really short—47,094 words, to be exact. I read it for the first time in a few hours at a swim meet (the aptness of the setting wasn’t clear to me until Chapter 8) and probably would have finished sooner had it not been for the snatches of Eminem coming from somebody’s boombox. You can count the book’s speaking roles on your fingers, and any high school sophomore can skim it the night before the big exam. Assign that to millions of teenagers for sixty-odd years, and a Great American Novel is born. What is it about the proposal that strikes me as so disturbing?’ Reading through an article describing a local government measure, I feel opposition rising within me. Normally, forming an opinion about such things would take me some time. But not here. The proposal instantly strikes me as unjust. My reaction is not just intellectual; it is visceral. My emotions are engaged. My imagination is exercised. As I imagine the proposal playing out in practice, the distinctive brand of injustice seems to be jumping out of every word on the page.

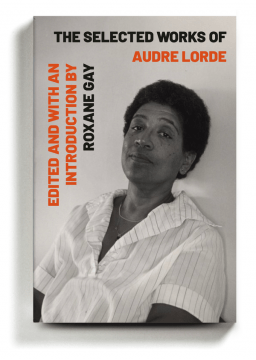

What is it about the proposal that strikes me as so disturbing?’ Reading through an article describing a local government measure, I feel opposition rising within me. Normally, forming an opinion about such things would take me some time. But not here. The proposal instantly strikes me as unjust. My reaction is not just intellectual; it is visceral. My emotions are engaged. My imagination is exercised. As I imagine the proposal playing out in practice, the distinctive brand of injustice seems to be jumping out of every word on the page. Lorde loved to be in dialogue, loved thinking with others, with her comrades and lovers. She is never alone on the page. Even her short essays come festooned with long lines of acknowledgment to those who have sharpened their ideas. Ghosts flock her essays. She writes to the ancestors and to women she meets in the headlines of the newspaper — missing women, murdered women, naming as many as she can, the sort of rescue and care for the dead that one sees in the work of Saidiya Hartman and Christina Sharpe. In “The Cancer Journals,” in which she documented her diagnosis of breast cancer, she noted: “I carry tattooed upon my heart a list of names of women who did not survive, and there is always a space left for one more, my own.”

Lorde loved to be in dialogue, loved thinking with others, with her comrades and lovers. She is never alone on the page. Even her short essays come festooned with long lines of acknowledgment to those who have sharpened their ideas. Ghosts flock her essays. She writes to the ancestors and to women she meets in the headlines of the newspaper — missing women, murdered women, naming as many as she can, the sort of rescue and care for the dead that one sees in the work of Saidiya Hartman and Christina Sharpe. In “The Cancer Journals,” in which she documented her diagnosis of breast cancer, she noted: “I carry tattooed upon my heart a list of names of women who did not survive, and there is always a space left for one more, my own.” Adam Tooze in The Guardian:

Adam Tooze in The Guardian: Lynn Parramore interviews Lance Taylor over at INET:

Lynn Parramore interviews Lance Taylor over at INET: Michael Scott Moore in the LA Review of Books:

Michael Scott Moore in the LA Review of Books: Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin talk to C. J. Polychroniou in Boston Review:

Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin talk to C. J. Polychroniou in Boston Review:

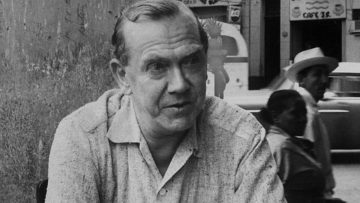

Joseph Conrad’s death made Graham Greene feel, at 19, sitting on a beach in Yorkshire, ‘as if there was a kind of “blank” in the whole of contemporary literature’. Greene’s own death in 1991, aged 87, had a similar effect on many younger writers, myself included. For John le Carré, his most obvious successor, Greene had ‘carried the torch of English literature, almost alone’. His cool fugitive presence, in Martin Amis’s phrase, had been there all our reading lives. In an age of diminishing faith, he had used Catholic parables in a way that lent them a power beyond their biblical origins, mining the gospels rather as le Carré has mined the Cold War. Shaking his hand in Moscow in 1987, Mikhail Gorbachev spoke for an international audience: ‘I have known you for some years, Mr Greene’ — although it was unclear whether as an admirer of his novels, or if Russia’s president had seen his name in intelligence reports concerning Latin America.

Joseph Conrad’s death made Graham Greene feel, at 19, sitting on a beach in Yorkshire, ‘as if there was a kind of “blank” in the whole of contemporary literature’. Greene’s own death in 1991, aged 87, had a similar effect on many younger writers, myself included. For John le Carré, his most obvious successor, Greene had ‘carried the torch of English literature, almost alone’. His cool fugitive presence, in Martin Amis’s phrase, had been there all our reading lives. In an age of diminishing faith, he had used Catholic parables in a way that lent them a power beyond their biblical origins, mining the gospels rather as le Carré has mined the Cold War. Shaking his hand in Moscow in 1987, Mikhail Gorbachev spoke for an international audience: ‘I have known you for some years, Mr Greene’ — although it was unclear whether as an admirer of his novels, or if Russia’s president had seen his name in intelligence reports concerning Latin America. In 2014, Kate Livingston

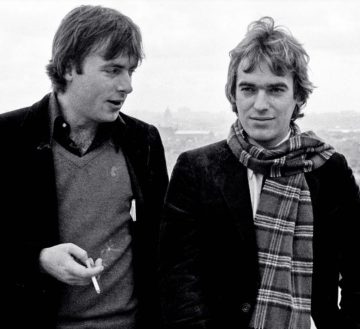

In 2014, Kate Livingston  It would hardly have surprised Christopher Hitchens, his unsanguine views of the afterlife under no bushel, that among the trials and stations awaiting his departed soul there would be passage through a Martin Amis novel (he had already endured being packed into The Pregnant Widow in the character of Nicholas Shackleton). Inside Story – the Fleet Street tease of the title notwithstanding – evinces a protective, even proprietary attitude towards the goods to be delivered. The cover features an arresting image of the two grands amis – both formerly of this parish – on the cusp of their prime. Hitchens is on the left, holding his cigarette mid-abdomen like a paintbrush. His as yet unravaged face seems to be gauging whether his last remark has landed with Amis, who looks into the distance, appearing simultaneously satisfied and anxious.

It would hardly have surprised Christopher Hitchens, his unsanguine views of the afterlife under no bushel, that among the trials and stations awaiting his departed soul there would be passage through a Martin Amis novel (he had already endured being packed into The Pregnant Widow in the character of Nicholas Shackleton). Inside Story – the Fleet Street tease of the title notwithstanding – evinces a protective, even proprietary attitude towards the goods to be delivered. The cover features an arresting image of the two grands amis – both formerly of this parish – on the cusp of their prime. Hitchens is on the left, holding his cigarette mid-abdomen like a paintbrush. His as yet unravaged face seems to be gauging whether his last remark has landed with Amis, who looks into the distance, appearing simultaneously satisfied and anxious.