Category: Archives

It’s Dante’s Hell—We’re Just Living In It

Nick Ripatrazone in Humanities:

The Latin renders to “who is blessed for ever” and concludes an enigmatic, brief paragraph. First published in 1294, La Vita Nuova is a tantalizing prelude to the Florentine poet’s masterpiece, La Commedia, known today as The Divine Comedy. For centuries, readers and scholars have pored over La Vita Nuova (Italian for, literally, the new life)—convinced, as we often are, that a gifted writer’s nascent work contains the answers to longstanding mysteries.

The Latin renders to “who is blessed for ever” and concludes an enigmatic, brief paragraph. First published in 1294, La Vita Nuova is a tantalizing prelude to the Florentine poet’s masterpiece, La Commedia, known today as The Divine Comedy. For centuries, readers and scholars have pored over La Vita Nuova (Italian for, literally, the new life)—convinced, as we often are, that a gifted writer’s nascent work contains the answers to longstanding mysteries.

La Vita Nuova’s ultimate paragraph follows a sonnet that Dante wrote for “two gracious ladies” of “noble lineage.” The poem begins: “Beyond the widest of the circling spheres / A sigh which leaves my heart aspires to move.” The sigh was a heavy one; a protracted sigh, in fact, that Dante had exhaled for much of his life. “As it nears / Its goal of longing in the realms above / The pilgrim spirit sees a vision”—a vision of Beatrice, the woman he loved for much of his life. “This much,” the sonnet concludes, “I know well.”

Dante finishes La Vita Nuova by describing that his sonnet was followed by “a marvellous vision in which I saw things which made me decide to write no more of this blessed one until I could do so more worthily.” Dante promises that he will write toward her glory, “as she indeed knows,” and he prays that God will grant him enough years so that he can “compose concerning her what has never been written in rhyme of any woman.” Even more, Dante prays—he pleads—that “my soul may go to see the glory of my lady, that is of the blessed Beatrice, who now in glory beholds the face of Him.” As in much of Dante’s work, it is both humble and ambitious: The poet wished to join his beloved in eternity while affirming that she is in sight of the divine. The request concludes with that Latin phrase, appended with a bit of mystery: Is it God who is blessed forever, or is it Beatrice?

Was there a meaningful distinction between the two—for Dante?

More here.

Why Do We Age?

Dana Smith in The New York Times:

According to some estimates, consumers spend $62 billion a year on “anti-aging” treatments. But while creams, hair dyes and Botox can give the impression of youth, none of them can roll back the hands of time.

According to some estimates, consumers spend $62 billion a year on “anti-aging” treatments. But while creams, hair dyes and Botox can give the impression of youth, none of them can roll back the hands of time.

Scientists are working to understand the biological causes of aging in the hope of one day being able to offer tools to slow or stop its visible signs and, more important, age-related diseases. These underlying mechanisms are often called “the hallmarks of aging.” Many fall into two broad categories: general wear and tear on a cellular level, and the body’s decreasing ability to remove old or dysfunctional cells and proteins. “The crucial thing about the hallmarks is that they are things that go wrong during aging, and if you reverse them,” you stand to live longer or be healthier while you age, said Dame Linda Partridge, a professorial research fellow in the division of biosciences at University College London who helped develop the aging hallmarks framework.

So far, the research has primarily been conducted in animals, but experts are gradually expanding into humans. In the meantime, understanding how aging works can help us put advice and information about the latest “breakthrough” into context, said Venki Ramakrishnan, a biochemist and Nobel laureate who wrote about many of the hallmarks of aging in his new book, “Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for Immortality.”

More here.

Thursday Poem

Love is not Concerned

Love is not concerned

with whom you pray

or where you slept

the night you ran away

from home

love is concerned

that the beating of your heart

should kill no one.

by Allice Walker

from Her Blue Body Everything We Know

Harvest Books, 1998

Wednesday, March 20, 2024

Between machine and eye

Morgan Meis at The Easel:

This photograph is the kind of photograph you’d throw away. If you’re working with a digital camera, you would immediately delete it. It’s a disaster. Trash it and move on. There’s a big metal bar in the middle of the shot. It must be from a gate or something. The metal bar not only dominates the very center of the picture, it’s also so close to the camera that the bar is blurred at the top. Technically speaking, that is a no-no. This is a terrible photograph.

This photograph is the kind of photograph you’d throw away. If you’re working with a digital camera, you would immediately delete it. It’s a disaster. Trash it and move on. There’s a big metal bar in the middle of the shot. It must be from a gate or something. The metal bar not only dominates the very center of the picture, it’s also so close to the camera that the bar is blurred at the top. Technically speaking, that is a no-no. This is a terrible photograph.

And yet, the very thing that seems at first so terrible is what makes the picture so compelling. If the obscuring bar wasn’t there, we would know too much, visually speaking, about the woman behind the bar. As it is, she is obscured in just the right way. Her one looming and seemingly unblinking eye gets all the attention it needs and deserves. The woman further in the background, with her timid glance and questioning mouth, only heightens the self-assured intensity of the giant eye.

Look closer.

More here.

It’s Time to Reinvent the Rape Kit

Pagan Kennedy in Undark:

I’ve spent the last five years digging deep into the history of American crime forensics, writing a widely read 2020 New York Times story about the origins of the rape kit and interviewing people for a forthcoming book. I’ve learned that the rape kit is the unsung hero of forensics — when used correctly, it can identify violent criminals and also prevent wrongly accused men from going to prison. But unfortunately, it has never really been given a chance to work. It could be so much better.

I’ve spent the last five years digging deep into the history of American crime forensics, writing a widely read 2020 New York Times story about the origins of the rape kit and interviewing people for a forthcoming book. I’ve learned that the rape kit is the unsung hero of forensics — when used correctly, it can identify violent criminals and also prevent wrongly accused men from going to prison. But unfortunately, it has never really been given a chance to work. It could be so much better.

More here.

How Capitalism Became a Threat to Democracy

Mordecai Kurz at Project Syndicate:

Does free-market capitalism buttress democracy, or does it unleash anti-democratic forces? This question first emerged in the Age of Enlightenment, when capitalism was viewed optimistically and welcomed as a vehicle of liberation from the rigid feudal order. Many envisioned an equal-opportunity society of small producers and consumers, where no one would have undue market power, and where prices would be determined by the “invisible hand.” Under such conditions, democracy and capitalism are two sides of the same coin.

Does free-market capitalism buttress democracy, or does it unleash anti-democratic forces? This question first emerged in the Age of Enlightenment, when capitalism was viewed optimistically and welcomed as a vehicle of liberation from the rigid feudal order. Many envisioned an equal-opportunity society of small producers and consumers, where no one would have undue market power, and where prices would be determined by the “invisible hand.” Under such conditions, democracy and capitalism are two sides of the same coin.

Domestic propaganda in the United States has pushed the same optimistic vision over the past century, aiming to convince voters that free-market capitalism is essential to the “American Way,” and that their liberty depends on supporting unfettered free enterprise and distrusting government. But economic developments in recent decades suggest that we should re-examine such beliefs.

To see why, allow me first to clarify some background ideas about what I call technological competition among innovating companies seeking to amass market power.

More here.

Geoffrey West: The Simplicity, Unity and Complexity of Life

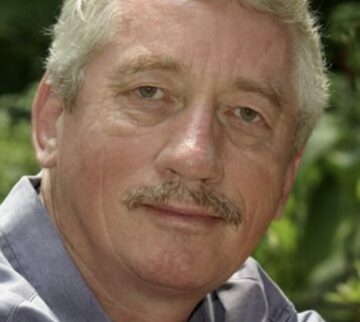

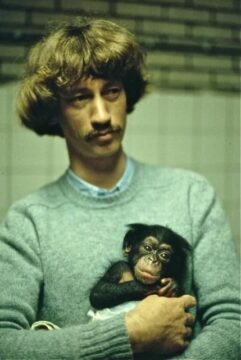

Frans de Waal remembered for bringing apes ‘a little closer to humans’

Carol Clark at the website of Emory University:

Emory University primatologist Frans de Waal — who pioneered studies of animal cognition while also writing best-selling books that helped popularize the field around the globe — passed away March 14, 2024, from stomach cancer.

Emory University primatologist Frans de Waal — who pioneered studies of animal cognition while also writing best-selling books that helped popularize the field around the globe — passed away March 14, 2024, from stomach cancer.

De Waal, Charles Howard Candler Professor Emeritus of Psychology and former director of the Living Links Center for the Advanced Study of Ape and Human Evolution at the Emory National Primate Research Center, was 75.

From his groundbreaking 1982 book “Chimpanzee Politics: Power and Sex Among Apes” to 2019’s “Mama’s Last Hug: Animal Emotions and What They Tell Us About Ourselves,” de Waal shattered long-held ideas about what it means to be an animal and a human.

“One thing that I’ve seen often in my career is claims of human uniqueness that fall away and are never heard from again,” de Waal said in 2014. “We always end up overestimating the complexity of what we do. That’s how you can sum up my career: I’ve brought apes a little closer to humans but I’ve also brought humans down a bit.”

More here.

Wednesday Poem

The Lark. The Thrush. The Starling.

—Poems from Issa -excerpt

In the next life,

butterfly,

a thousand years from now,

we’ll sit like this

again

under the tree

in the dust,

hearing it, this

great thing

~~~~

I sit in my room.

Outside, haze.

The whole world

is haze

and I can’t figure out

one room.

by C.K. Williams

from Selected Poems

Noonday Press, 1994

Dunes aren’t just for sand worms. Here’s why they matter on Earth

Allyson Chiu in The Washington Post:

The famed coastal dunes that inspired the shifting sand landscape of the desert planet Arrakis in Frank Herbert’s science fiction novel “Dune” are also under siege — from climate change and human development.

The famed coastal dunes that inspired the shifting sand landscape of the desert planet Arrakis in Frank Herbert’s science fiction novel “Dune” are also under siege — from climate change and human development.

More here.

These ‘movies’ of proteins in action are revealing the hidden biology of cells

Ewen Callaway in Nature:

Since the 1950s, scientists have had a pretty good idea of how muscles work. The protein at the centre of the action is myosin, a molecular motor that ratchets itself along rope-like strands of actin proteins — grasping, pulling, releasing and grasping again — to make muscle cells contract.

Since the 1950s, scientists have had a pretty good idea of how muscles work. The protein at the centre of the action is myosin, a molecular motor that ratchets itself along rope-like strands of actin proteins — grasping, pulling, releasing and grasping again — to make muscle cells contract.

The basics were first explained in a pair of landmark papers in Nature1,2, and they have been confirmed and elaborated on by detailed molecular maps of myosin and its partners. Researchers think that myosin generates force by cocking back the long lever-like arm that is attached to the motor portion of the protein.

The only hitch is that scientists had never seen this fleeting pre-stroke state — until now.

In a preprint published in January3, researchers used a cutting-edge structural biology technique to record this moment, which lasts just milliseconds in living cells.

More here.

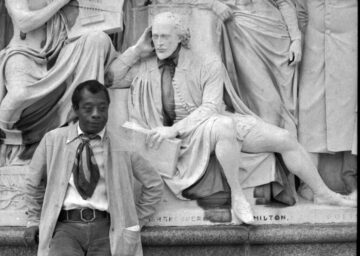

James Baldwin At The Centennial

Lawrence Weschler and Rich Blint at Wondercabinet:

Weschler: It’s interesting in this context, you mentioned a second ago Giovanni’s Room, where part of the story is clearly about a deeply closeted white figure, an American in Paris, who gets involved with somebody who is clearly much more at ease with his sexuality. The relationship just curdles and he destroys both himself and his lover through his inability to be free. And he’s not only talking about gayness in that situation.

Weschler: It’s interesting in this context, you mentioned a second ago Giovanni’s Room, where part of the story is clearly about a deeply closeted white figure, an American in Paris, who gets involved with somebody who is clearly much more at ease with his sexuality. The relationship just curdles and he destroys both himself and his lover through his inability to be free. And he’s not only talking about gayness in that situation.

Blint: It’s all about American innocence. What Baldwin does in that novel that I find so compelling—and to put in a quick little plug here, a panel that Bill T. Jones and I have been working on for the festival called “After Giovanni’s Room: Baldwin and Queer Futurity,” will be held at NYLA—is precisely to this point. {For a video of the eventual panel, see here.} David, the lead character in that novel, is just part of what Baldwin calls the “ignorant armies”: these white men who take their position, life, trajectory in the world for granted, in a white patriarchal society. {It’s perhaps worth noting in this context that Giovanni’s Room came out within a few months, in 1955-56, of Graham Greene’s prescient Vietnam novel The Quiet American.—LW} It’s a story of innocence, of the refusal to be sullied by the contradictions of history, which is partly why Giovanni is there as a foil.

more here.

James Baldwin’s Another Country with Rich Blint

Tuesday, March 19, 2024

Heloise and Abelard

Morgan Meis at Slant Books:

It is one of the great love stories of history and therefore inherently interesting because who isn’t interested in a great love story? Actually, it is a terrible love story as well. That is also what makes it interesting. The love part of the love story only lasted about a year in the early twelfth century. That’s when the great philosopher Peter Abelard was in Paris teaching and making fools of the other great minds to be found in Paris at the time, at least as he tells it, but other sources seem to confirm that Abelard was indeed just sharper and more witty and quicker on his feet than anyone else, plus he was a damn good poet and wrote wonderful popular songs and was handsome as hell.

It is one of the great love stories of history and therefore inherently interesting because who isn’t interested in a great love story? Actually, it is a terrible love story as well. That is also what makes it interesting. The love part of the love story only lasted about a year in the early twelfth century. That’s when the great philosopher Peter Abelard was in Paris teaching and making fools of the other great minds to be found in Paris at the time, at least as he tells it, but other sources seem to confirm that Abelard was indeed just sharper and more witty and quicker on his feet than anyone else, plus he was a damn good poet and wrote wonderful popular songs and was handsome as hell.

Also in Paris was Heloise, a somewhat mysterious person (from whence did she spring?) who managed to become a great Latinist and though a young woman perhaps in her late teens or early twenties was known to be amongst the more learned people of her age, especially when it came to those much revered classical authors like Cicero and Seneca and the like. Also she was beautiful of course.

More here.

Frans de Waal (RIP) and the Origins of War

John Horgan at his own website:

I interviewed de Waal in 2007 while researching my book The End of War. At the time, high-profile scientists were promoting the notion that humans are genetically predisposed to war. As evidence, they cited the violence of our closest genetic relatives, chimpanzees. In his influential 1996 book Demonic Males: Apes and the Origins of Human Violence, anthropologist Richard Wrangham declared: “Chimpanzee-like violence preceded and paved the way for human war, making modern humans the dazed survivors of a continuous, five-million-year habit of lethal aggression.” This hypothesis, which I call the deep-roots theory of war, was embraced by public intellectuals like Steven Pinker and Francis Fukuyama.

I interviewed de Waal in 2007 while researching my book The End of War. At the time, high-profile scientists were promoting the notion that humans are genetically predisposed to war. As evidence, they cited the violence of our closest genetic relatives, chimpanzees. In his influential 1996 book Demonic Males: Apes and the Origins of Human Violence, anthropologist Richard Wrangham declared: “Chimpanzee-like violence preceded and paved the way for human war, making modern humans the dazed survivors of a continuous, five-million-year habit of lethal aggression.” This hypothesis, which I call the deep-roots theory of war, was embraced by public intellectuals like Steven Pinker and Francis Fukuyama.

I discussed the deep-roots theory with de Waal on June 12, 2007, at the Yerkes Primate Research Center in Georgia, which houses chimpanzees and monkeys. De Waal was tall with sandy-colored hair. He still spoke with a faint Dutch accent, although he left his native Holland in the 1980s. We chatted in a watchtower overlooking a yard where three male chimps and a dozen females lolled, lazily nitpicking and sniffing each other.

Against this backdrop, de Waal heatedly rejected the widespread belief in “some sort of blind aggressive drive that makes us go to war.”

More here.

Frans de Waal: The surprising science of alpha males

Acclaimed primatologist Frans de Waal dies at 75

Editor’s Note: I never met Frans in person but we exchanged scores of emails and he even wrote for 3QD for a while. He was, in addition to being one of the most distinguished scientists of our time, a brilliant writer and explicator of difficult science. He will be very much missed by many, including me. I had no idea he was ill and was shocked to hear of his death at the young age of 75. His writings for 3QD can be seen here.

From Phys.org:

The Netherlands-born scientist spent decades studying chimpanzees and apes, and his biological research eventually helped debunk the theory that primates including humans were naturally “nasty” and aggressive competitors.

The Netherlands-born scientist spent decades studying chimpanzees and apes, and his biological research eventually helped debunk the theory that primates including humans were naturally “nasty” and aggressive competitors.

“De Waal shattered long-held ideas about what it means to be an animal and a human,” Emory, based in Atlanta in the US state of Georgia, said in its statement.

“He demonstrated the roots of human nature in our closest living relatives through his studies of conflict resolution, reconciliation, cooperation, empathy, fairness, morality, social learning and culture in chimpanzees, bonobos and capuchin monkeys.”

Lynne Nygaard, chair of Emory’s Department of Psychology, remembered de Waal as “an extraordinarily deep thinker” who could offer “insights that cut across disciplines.”

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Portrait of a Romantic

He is in love with the land that is always over

The next hill and the next, with the bird that is never

Caught, with the room beyond the looking-glass.

He likes the half-hid, the half-heard, the half-lit,

The man in the fog, the road without an ending,

Stray pieces of torn words to piece together.

He is well aware that man is always lonely,

Listening for an echo of his cry, crying for the moon,

Making the moon his mirror, weeping in the night.

He often dives in the deep-sea undertow

Of the dark and dreaming mind. He turns at corners,

Twists on his heel to trap his following shadow.

He is haunted by the face behind the face.

He searches for last frontiers and lost doors.

He tries to climb the wall around the world.

by: A. S. J. Tessimond

from Poetic Outlaws

Ozempic Gets the Oprah Treatment in a New TV Special

Jamie Ducharme in Time:

Weight-loss drugs like Ozempic, Wegovy, and Zepbound are already extremely popular: by 2030, about 10% of the U.S. population will be on one of these drugs and the category’s sales will surpass $100 billion, according to some projections. On March 18, they got another major cultural boost from Oprah Winfrey, who shared her own experience with—and support for—these medications in an ABC special called “Shame, Blame and the Weight Loss Revolution.”

Weight-loss drugs like Ozempic, Wegovy, and Zepbound are already extremely popular: by 2030, about 10% of the U.S. population will be on one of these drugs and the category’s sales will surpass $100 billion, according to some projections. On March 18, they got another major cultural boost from Oprah Winfrey, who shared her own experience with—and support for—these medications in an ABC special called “Shame, Blame and the Weight Loss Revolution.”

During the special, Winfrey talked about how using one of these weight-loss drugs (she did not say which) changed her life and opened her eyes to the reality that obesity is a disease, rather than a choice. “All these years, I thought all of the people who never had to diet were just using their willpower, and they were for some reason stronger than me,” Winfrey said.

More here.