Category: Archives

Tuesday Poem

My Mother

My mother writes from Trenton,

a comedian to the bone

but underneath, serious

and all heart. “Honey,” she says

“be a mensch and Mary too,

it’s no good to worry, you

are doing the best you can

your Dad and everyone

thinks you turned out very well

as long as you pay your bills

nobody can say a word

you can tell them to drop dead

so save a dollar it can’t

hurt—remember Frank you went

to highschool with? he still lives

with his wife’s mother, his wife

works while he writes his books and

did he ever sell a one

the four kids run around naked

36 and he’s never had,

you’ll forgive my expression,

even a pot to piss in

or a window to throw it,

such a smart boy he couldn’t

read the footprints on the wall

honey you think you know all

the answers you don’t, please try

to put some money away

believe me it wouldn’t hurt

artist shmartist life’s too short

for that kind of, forgive me,

horseshit, I know what you want

better than you, all that counts

is to make a good living

and the best of everything,

as Sholem Aleichem said

he was a great writer did

you ever read his books dear,

you should make what he makes a year

anyway he says someplace

Poverty is no disgrace

but it’s no honor either

that’s what I say,

…………………..love,

…………………………..Mother”

by Robert Mezey

from Naked Poetry

Bobbs-Merrill, 1969

The Science of Forming Healthy Habits

Theresa Barger in Discover:

During her first year of college, Elaina Cosentino bought a fitness band and began walking 10,000 steps a day. Through a friendly competition with friends, she kept it up for four years. But during her first semester of graduate school, her routine changed and she fell out of the habit. Then her mother passed away between her first and second semesters, and it “truly took everything out of me to just get up and go to class,” says Cosentino, a physical therapist. “I did go for an occasional mind-clearing walk every now and then during that time, as walking was something familiar to me and I always loved the way I felt afterwards.”

During her first year of college, Elaina Cosentino bought a fitness band and began walking 10,000 steps a day. Through a friendly competition with friends, she kept it up for four years. But during her first semester of graduate school, her routine changed and she fell out of the habit. Then her mother passed away between her first and second semesters, and it “truly took everything out of me to just get up and go to class,” says Cosentino, a physical therapist. “I did go for an occasional mind-clearing walk every now and then during that time, as walking was something familiar to me and I always loved the way I felt afterwards.”

But the combined pressures of “the weight of the pandemic, not having family around, going through grad school virtually and still going through the grieving process” drove the Rhode Island resident to search for something more consistent. “When I went back to walking every day, reforming the habit was bringing myself back down to Earth. It’s the one thing I can control every day.” The two major components necessary to start and stick to a habit are ease and reward, says research psychologist Wendy Wood, author of the book, Good Habits, Bad Habits, The Science of Making Positive Changes That Stick, who has studied habits for three decades. “If you’re trying to repeat a behavior, then willpower and motivation are not really the way to go. They’re what start you but they’re not going to help you persist,” she says. “Habits are not part of our conscious thought.”

By contrast, New Year’s resolutions are often touted by gyms or weight loss companies trying to sell memberships — and can be particularly tricky to adhere to. Starting a habit and sticking to it has to come from you, not external forces. We can’t fight human nature, but we change our behavior by understanding it. And while study results vary on how long it takes to form a habit, on average, according to research published in the British Journal of General Practice in 2012, forming a new habit takes 66 days. So what’s the secret to getting through the months-long process and forging lasting, healthy habits?

More here.

Behind the bespoke cells of immunotherapy

From Nature:

It seemed like a very promising cancer immunotherapy lead. CHO Pharma, in Taiwan, had discovered that it was possible to target solid tumours with an antibody against a cell-surface glycolipid called SSEA-4.1 This antigen is present during embryonic development, but not seen on human cells again — until they turn into cancer cells.2 The company turned to Lan Bo Chen, a recently retired Harvard pathologist, to help develop this work into an anti-cancer therapy for solid tumours. “It is highly reasonable to imagine that we can use SSEA-4, overexpressed on cancer cells, as a target for CAR-T,” says Chen, now in his role as senior technology advisor for CHO Pharma.

It seemed like a very promising cancer immunotherapy lead. CHO Pharma, in Taiwan, had discovered that it was possible to target solid tumours with an antibody against a cell-surface glycolipid called SSEA-4.1 This antigen is present during embryonic development, but not seen on human cells again — until they turn into cancer cells.2 The company turned to Lan Bo Chen, a recently retired Harvard pathologist, to help develop this work into an anti-cancer therapy for solid tumours. “It is highly reasonable to imagine that we can use SSEA-4, overexpressed on cancer cells, as a target for CAR-T,” says Chen, now in his role as senior technology advisor for CHO Pharma.

CAR-T therapy works by genetically engineering a person’s own T cells in such a way that they recognize and attack cancer cells. This involves creating a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) from an antibody against a target on the cell. But CAR-T therapy was designed for blood cancers so it needs several adaptations to make it suitable for the treatment of solid tumours.3 The cells need to be directed to the site of the tumour, survive in the tumour’s local microenvironment, and act only on tumour cells, not on healthy cells nearby. But, when Chen tried to create CAR-T cells against SSEA-4, he hit a few obstacles. First it took him a long time to get his hands on a humanized SSEA-4 antibody suitable for adaptation. When he finally had one, he still had to find a way to turn that antibody into a CAR. And then to insert the CAR into a human T cell using lentiviral transduction.

More here.

In Our Time: Fritz Lang

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FmzVRe_JYws

Hating Dave Eggers

Lisa Borst at n+1:

Eggers is hardly a systems novelist: his literary sensibilities, like his career, tend toward the monomaniacal. His writing in the past two decades has involved a suspiciously prolific series of smug morality tales fictionalizing or nonfictionalizing real people—a heroic Sudanese refugee, a heroic Yemeni coffee importer later accused of racketeering, Donald Trump—as well as novels about loners in perilous circumstances. He has also written children’s books, left-of-center comedic op-eds, and articles for the New Yorker about human rights and how much he loves wine. But evident throughout his literary output, as in his incoherent and self-congratulatory apparatus of publishing programs, bookselling platforms, and children’s literacy programs, is an ongoing fascination with epic, world-conquering ambition. The characters in A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, I was embarrassed to reread, are “sure that we are on to something epochal . . . sure that we speak for others, that we speak for millions”; in his 2006 foreword to Infinite Jest, Eggers lingers, enviously and, I think, not un-Bezosishly, on Wallace’s all-seeing book as an example of the “human possibility [for] leaps in science and athletics and art and thought.”

Eggers is hardly a systems novelist: his literary sensibilities, like his career, tend toward the monomaniacal. His writing in the past two decades has involved a suspiciously prolific series of smug morality tales fictionalizing or nonfictionalizing real people—a heroic Sudanese refugee, a heroic Yemeni coffee importer later accused of racketeering, Donald Trump—as well as novels about loners in perilous circumstances. He has also written children’s books, left-of-center comedic op-eds, and articles for the New Yorker about human rights and how much he loves wine. But evident throughout his literary output, as in his incoherent and self-congratulatory apparatus of publishing programs, bookselling platforms, and children’s literacy programs, is an ongoing fascination with epic, world-conquering ambition. The characters in A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, I was embarrassed to reread, are “sure that we are on to something epochal . . . sure that we speak for others, that we speak for millions”; in his 2006 foreword to Infinite Jest, Eggers lingers, enviously and, I think, not un-Bezosishly, on Wallace’s all-seeing book as an example of the “human possibility [for] leaps in science and athletics and art and thought.”

more here.

The Temptations Of Christopher Hitchens

Ross Douthat at The New Statesman:

Over the Thanksgiving holiday the Financial Times columnist Janan Ganesh expressed a sentiment I hear from time to time among connoisseurs of punditry – that our era, the age of Trumpism and wokeness and Covid controversy, badly misses the words and wits of Christopher Hitchens, who was taken from the stage before his time. Ganesh offered a particularly interesting version of this take, because he went halfway to conceding something that Hitchens’ critics (I was one of them) might say has become more palpable since his passing in 2011: that his great talents were expended on causes that have not exactly stood the test of time. But Ganesh framed this reality as an indictment of the somewhat-empty – dare one say, decadent – times in which Hitch lived:

Over the Thanksgiving holiday the Financial Times columnist Janan Ganesh expressed a sentiment I hear from time to time among connoisseurs of punditry – that our era, the age of Trumpism and wokeness and Covid controversy, badly misses the words and wits of Christopher Hitchens, who was taken from the stage before his time. Ganesh offered a particularly interesting version of this take, because he went halfway to conceding something that Hitchens’ critics (I was one of them) might say has become more palpable since his passing in 2011: that his great talents were expended on causes that have not exactly stood the test of time. But Ganesh framed this reality as an indictment of the somewhat-empty – dare one say, decadent – times in which Hitch lived:

“The trouble is, the artist dwarfed his canvas. Hitchens had the misfortune to peak during one of world history’s blander interludes.

more here.

Sunday, January 2, 2021

Joyce Carol Oates on the lifelong obsessions of Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Joyce Carol Oates in Prospect:

Of all writers, Fyodor Dostoyevsky is the great artist of obsession. It is not surprising, therefore, that his monumental works—Crime and Punishment, The Possessed, The Idiot, The Brothers Karamazov—are seeded in his shorter works of fiction, as if in embryo. From the wildly romantic and effusive “White Nights” (1848) to the parable-like “Dream of a Ridiculous Man” (1877), these tales explore themes taken up in minute detail in the novels, in which Dostoyevsky’s sense of the tragic predicament of humankind is given its fullest expression: that human beings recognise the good, but succumb to evil; that, though knowing that love is the highest value, they rejoice in their own wickedness, like the “ridiculous man,” a perverse saviour who corrupts the innocent:

Of all writers, Fyodor Dostoyevsky is the great artist of obsession. It is not surprising, therefore, that his monumental works—Crime and Punishment, The Possessed, The Idiot, The Brothers Karamazov—are seeded in his shorter works of fiction, as if in embryo. From the wildly romantic and effusive “White Nights” (1848) to the parable-like “Dream of a Ridiculous Man” (1877), these tales explore themes taken up in minute detail in the novels, in which Dostoyevsky’s sense of the tragic predicament of humankind is given its fullest expression: that human beings recognise the good, but succumb to evil; that, though knowing that love is the highest value, they rejoice in their own wickedness, like the “ridiculous man,” a perverse saviour who corrupts the innocent:

“The dream encompassed thousands of years and left in me only a vague sensation… I only know that the cause of the Fall was I. Like a horrible trichina, like the germ of the plague infecting whole kingdoms, so did I infect with myself all that happy earth that knew no sin before me.”

Dostoyevsky is a fierce Christian visionary for whom “social realism” holds little interest, except as a backdrop for powerful dramas of good contending with evil. Unlike his fellow Russian Leo Tolstoy—whose prose evokes an astonishingly lifelike world of men and women of virtually every social class, who could write as vividly of a young girl’s first ball as of a young soldier’s first battle—Dostoyevsky is all foreground, his settings (cramped and febrile interiors, sweeping and anonymous cityscapes) incidental to the histrionic nature of his prose.

More here.

Beyond case counts: What Omicron is teaching us

Andrew Joseph and Helen Branswell in Stat News:

The Omicron wave in the United States is upon us.

The Omicron wave in the United States is upon us.

If you were fortunate enough to tune out from Covid-19 news over the holidays, you’re coming back to startling reports about record high case counts and, in some places, increases in hospitalizations. The wave will crest, of course; the question is when.

For now, experts say, the country still has a ways to go to get through the Omicron surge. Below, STAT outlines what Omicron is already teaching us as this phase of the pandemic plays out.

A reminder: Scientists have known about this variant for just a little over a month. While a tremendous amount has been learned in a stunningly short amount of time, our understanding will continue to be refined as data pour in and key questions are answered.

More here.

A Conversation with E.O. Wilson (1929–2021)

Alice Dreger in Quillette:

Alice Dreger: I know you’ve spoken about it many times before, but I would like to begin by asking you about the session at the 1978 AAAS [American Association for the Advancement of Science] conference during which you were rushed on the stage and a protester emptied a pitcher of water onto your head. By all accounts, the talk you then gave was very measured. How on Earth were you able to remain so calm after being physically assaulted?

Edward O. Wilson: I think I may have been the only scientist in modern times to be physically attacked for an idea. The idea of a biological human nature was abhorrent to the demonstrators and was, in fact, too radical at the time for a lot of people—probably most social scientists and certainly many on the far-Left. They just accepted as dogma the blank-slate view of the human mind—that everything we do and think is due to contingency, rather than based upon instinct like bodily functions and the urge to keep reproducing. These people believe that everything we do is the result of historical accidents, the events of history, the development of personality through experience.

Edward O. Wilson: I think I may have been the only scientist in modern times to be physically attacked for an idea. The idea of a biological human nature was abhorrent to the demonstrators and was, in fact, too radical at the time for a lot of people—probably most social scientists and certainly many on the far-Left. They just accepted as dogma the blank-slate view of the human mind—that everything we do and think is due to contingency, rather than based upon instinct like bodily functions and the urge to keep reproducing. These people believe that everything we do is the result of historical accidents, the events of history, the development of personality through experience.

That was firmly believed in 1978 by a wide part of the population, but particularly by the political Left. And it was thought at the time that raising the specter of a biological basis for human behavior was not only wrong, but a justification for war, sexism, and racism.

More here.

Our fondness for narratives is driving us mad

Jonathan Gottschall in the Boston Globe:

Stories are celebrated by great artists, thought leaders, and scientists as our best hope for reducing bigotry, building empathy, and ultimately encouraging us to behave more humanely. But how does this match up with the current state of the world?

Stories are celebrated by great artists, thought leaders, and scientists as our best hope for reducing bigotry, building empathy, and ultimately encouraging us to behave more humanely. But how does this match up with the current state of the world?

We are living inside a digitally driven big bang of storytelling — a stunning expansion of the universe of stories across all media and genres. A 2020 Nielsen study reported that average Americans now consume a whopping 12 hours of media per day, much of it in narrative form, including hours upon hours of fiction. Now that we have more storytelling than ever, has empathy increased apace? Are we doing a better job of understanding each other across ancient divides of race, class, gender, religion, and political orientation? If stories have such sunny effects, why has the big bang of storytelling coincided with an explosive growth of hostility and polarization rather than harmony and connection?

More here.

At Night Gardens Grow

Joanna Cresswell in lensculture:

Night has the power to change things, doesn’t it? Not just appearances, but atmospheres too. The way we feel, the thickness of the air, the intensity of sounds, our imaginations. Darkness—real, enveloping darkness—is a shaping force, and even the scenes we know the most can metamorphose within its depths.

Night has the power to change things, doesn’t it? Not just appearances, but atmospheres too. The way we feel, the thickness of the air, the intensity of sounds, our imaginations. Darkness—real, enveloping darkness—is a shaping force, and even the scenes we know the most can metamorphose within its depths.

In Paul Guilmoth’s new publication At Night Gardens Grow, the night becomes a stage for a strange, folkloric story, unfurling from the landscape the artist calls home. Concentrating on one field in particular, the book is a constellation of black and white images depicting ghostly figures and glowing foliage, spiderwebs and moths, baptisms and waterfalls glistening at night. It’s a careful, deliberate edit, one that builds in an intense and palpable way, transporting us to a dark fictional world that teeters on the brink between dream and reality. There are symbols we know from age-old fables here—rabbits feet and wooden cabins, nymph-like, bathing women and mirrors in forests—but they’re different somehow, transformed in the darkness, like fairytales gone awry.

More here.

The Case Against the Trauma Plot

Parul Sehgal in The New Yorker:

It was on a train journey, from Richmond to Waterloo, that Virginia Woolf encountered the weeping woman. A pinched little thing, with her silent tears, she had no way of knowing that she was about to be enlisted into an argument about the fate of fiction. Woolf summoned her in the 1924 essay “Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown,” writing that “all novels begin with an old lady in the corner opposite”—a character who awakens the imagination. Unless the English novel recalled that fact, Woolf thought, the form would be finished. Plot and originality count for crumbs if a writer cannot bring the unhappy lady to life. And here Woolf, almost helplessly, began to spin a story herself—the cottage that the old lady kept, decorated with sea urchins, her way of picking her meals off a saucer—alighting on details of odd, dark density to convey something of this woman’s essence.

It was on a train journey, from Richmond to Waterloo, that Virginia Woolf encountered the weeping woman. A pinched little thing, with her silent tears, she had no way of knowing that she was about to be enlisted into an argument about the fate of fiction. Woolf summoned her in the 1924 essay “Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown,” writing that “all novels begin with an old lady in the corner opposite”—a character who awakens the imagination. Unless the English novel recalled that fact, Woolf thought, the form would be finished. Plot and originality count for crumbs if a writer cannot bring the unhappy lady to life. And here Woolf, almost helplessly, began to spin a story herself—the cottage that the old lady kept, decorated with sea urchins, her way of picking her meals off a saucer—alighting on details of odd, dark density to convey something of this woman’s essence.

Those details: the sea urchins, that saucer, that slant of personality. To conjure them, Woolf said, a writer draws from her temperament, her time, her country. An English novelist would portray the woman as an eccentric, warty and beribboned. A Russian would turn her into an untethered soul wandering the street, “asking of life some tremendous question.”

How might today’s novelists depict Woolf’s Mrs. Brown? Who is our representative character? We’d meet her, I imagine, in profile or bare outline. Self-entranced, withholding, giving off a fragrance of unspecified damage. Stalled, confusing to others, prone to sudden silences and jumpy responsiveness. Something gnaws at her, keeps her solitary and opaque, until there’s a sudden rip in her composure and her history comes spilling out, in confession or in flashback. Dress this story up or down: on the page and on the screen, one plot—the trauma plot—has arrived to rule them all. Unlike the marriage plot, the trauma plot does not direct our curiosity toward the future (Will they or won’t they?) but back into the past (What happened to her?). “For the eyeing of my scars, there is a charge,” Sylvia Plath wrote in “Lady Lazarus.” “A very large charge.” Now such exposure comes cheap.

More here.

Sunday Poem

After Lorca

The church is a business, and the rich

are the businessmen.

……………………………. When they pull on the bells, the

poor come piling in and when the poor man dies, he has a wooden

cross, and they rush through the ceremony.

But when the rich man dies, they

drag out the sacrament

and the golden cross, and go doucement, doucement

to the cemetery.

And the poor love it

and think it’s crazy.

by Robert Creeley

from Naked Poetry

publisher: Bobbs-Merrill, NY, 1969

doucement: slowly, gently

Desmond Tutu (1931 – 2021) theologian

E.O. Wilson (1929 – 2021) biologist

Betty White (1922 -2021) actress

Saturday, January 1, 2021

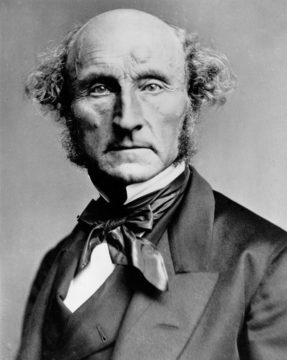

Why Academic Freedom Matters

Nishi Shah in The Raven:

Nishi Shah in The Raven:

In the midst of the 2020 protests for racial justice, I prepared to teach my annual July mini-course on free speech for incoming FLI (First-Generation and/or Low-Income) students at Amherst College. Almost all of these students are persons of color. My aim in this course is to show students how to analyze the reasoning in an important but difficult text from the history of philosophy, something for which most high schoolers have little training. The text I chose was John Stuart Mill’s famous defense of free speech in On Liberty. But I like to begin the course with a discussion of a specific free-speech controversy, so that, after reading On Liberty, students can reflect on whether this 19th century essay by a dead white male has something enlightening to say to us. Last summer, my idea was to have that initial discussion about Senator Tom Cotton’s recently published op-ed in the New York Times defending the federal government’s military response to the Black Lives Matter protests in Lafayette Square in Washington, D.C. After receiving heavy criticism from readers, the Times conducted a review, concluded that it should not have published the essay, issued a public apology, and eventually forced the resignation of James Bennet, the editor of the opinion page. Two Times opinion writers, Ross Douthat and Michelle Goldberg, wrote subsequent essays in the Times, one in favor (Goldberg) and one against (Douthat) these decisions. For the first day of class, I asked my students to read both essays along with the original Cotton op-ed, and write on the following question: Do you think the New York Times should have published Cotton’s essay? Why or why not?

More here.

On Language Games

Jon Baskin in The Point:

Jon Baskin in The Point:

For a country so often believed to be anti-intellectual, it is striking how much of American political conversation has come to revolve around seemingly pedantic quarrels about terminology. Critical race theory, which dominated media analysis of the Virginia governor’s race this November, might have been a new term to many who tuned into the political news in the days following the election, but the shape of the argument about its meaning and function was so familiar that it is hard not to reach for a psychoanalytic vocabulary when describing it. The neurotic process commences when a term or theory that had started life decades ago at some obscure intersection between academia and left-wing activism—before CRT, there was political correctness, intersectionality and identity politics—begins to be publicized by progressive activists and commentators as a superior way to talk about some broader set of social phenomena. Taking advantage of its newly expanded—and usually piecemeal—application, right-wing critics then respond by seizing on the term as a blanket pejorative for an approach to social problems they oppose, while simultaneously connecting it to various other charter members of their lexicon of Bad Things (like Nazism and… Kant?). At this point, progressive intellectuals accuse conservative columnists of peddling “absolute nonsense” while at the same time deriding ordinary people who begin to apply the term for being either dupes (for falling for a “moral panic”) or bigots (for using the term to soft-pedal their own prejudice). Both progressive accusations imply that the people who use the new terms inappropriately are, at the very least, hopelessly confused about the meaning of their own words, which in turn allows right-wing critics to reprise the familiar accusation that progressives are always lecturing people about what to call things. Now the process has reached its terminal phase: the concept is too ideologically freighted to serve as anything other than an occasion for meta-discussions about the debate itself (like this one), which means we are close to the end of one cycle—and the beginning of its compulsive repetition.

More here.

A Philosopher in Hard Times

Michael S. Roth in The LA Review of Books:

Michael S. Roth in The LA Review of Books:

SAMANTHA ROSE HILL’s intellectual biography of Hannah Arendt is a timely look at one of the most impactful, if elusive, 20th-century political thinkers. The book makes accessible key themes in Arendt’s work. Looking for a philosophical focus on creative work that escapes the mystical Teutonic fog of Heidegger? See the concept of natality described in The Human Condition. Concerned about the rise of populist authoritarianism? The Origins of Totalitarianism remains a bracing read, its conceptual flaws and political agenda less important today than its description of the aspiration to tyrannical control. Want to step back from political relevance to something more primary? Arendt’s late reflections on thinking and judgment will be powerful. In all these cases, and many more, Hill is a thoughtful guide.

The early biography is covered quickly. Hill doesn’t say much about the impact of the death of Hannah’s father, only noting with awkward foreshadowing that the loss did not diminish her “inherent wonder at being in the world.” Be that as it may, we know from Elisabeth Young-Bruehl’s more detailed 1982 biography that the seven-year-old Hannah maintained an unusually sunny disposition for months after her father’s death but a year later began acting out and succumbing to various ailments; Young-Bruehl understood this as Hannah’s way of grieving. The young girl’s family was unobservant, but she learned about her Jewish identity from the everyday antisemitism of the street. After her mother moved to East Prussia, a challenging place to be at the outbreak of World War I, Hannah took comfort in her books. Years later when asked by Günter Gaus why she had read Kant at such a young age, she responded, “I can either study philosophy or I can drown myself, so to speak.”

More here.