Anthony Lane in The New Yorker:

The hero of “A Hero,” the new film from Asghar Farhadi, is a sign painter and calligrapher named Rahim (Amir Jadidi). As the story begins, he leaves prison and is driven up the wall. To be precise, up a cliff of pale rock, rich in elaborate carvings, northeast of the Iranian city of Shiraz. The cliff is the home of a necropolis, Naqsh-e Rostam, and Rahim finds it covered in scaffolding; climbing high, he greets his brother-in-law, the rotund and genial Hossein (Alireza Jahandideh), who is working at the site. The wind whistles gently around them, and Hossein brews tea, close to the tomb of Xerxes the Great, a Persian king who died almost two and a half thousand years ago. Rahim, by contrast, is on a furlough for two days, after which—not unlike Eddie Murphy in “48 Hrs.” (1982)—he must return to prison. Observing the scene, you feel dizzy at the doubleness of time. It expands and contracts, either stretching far into the distance or slamming shut.

The hero of “A Hero,” the new film from Asghar Farhadi, is a sign painter and calligrapher named Rahim (Amir Jadidi). As the story begins, he leaves prison and is driven up the wall. To be precise, up a cliff of pale rock, rich in elaborate carvings, northeast of the Iranian city of Shiraz. The cliff is the home of a necropolis, Naqsh-e Rostam, and Rahim finds it covered in scaffolding; climbing high, he greets his brother-in-law, the rotund and genial Hossein (Alireza Jahandideh), who is working at the site. The wind whistles gently around them, and Hossein brews tea, close to the tomb of Xerxes the Great, a Persian king who died almost two and a half thousand years ago. Rahim, by contrast, is on a furlough for two days, after which—not unlike Eddie Murphy in “48 Hrs.” (1982)—he must return to prison. Observing the scene, you feel dizzy at the doubleness of time. It expands and contracts, either stretching far into the distance or slamming shut.

Something else, however, makes you no less uneasy, and that is Rahim’s smile. It looks friendly and generous, but it’s also weirdly weak, and it can fade like breath off a mirror. This is clever casting on Farhadi’s part; we warm to Rahim’s crestfallen charm, and instinctively feel him to be down on his luck, yet we don’t entirely trust him, and the film proceeds to back our initial hunch. What led to his incarceration was an unpaid debt. His creditor, Bahram (Mohsen Tanabandeh), is grave, dour, and disinclined to forgive, despite being related to Rahim by marriage. (Just to thicken the mood, Bahram is a dead ringer for the Mandy Patinkin character, Saul, in “Homeland.”) “I was fooled once by his hangdog look, that’s enough,” Bahram says of Rahim, and we can’t help wondering, Could the dog be fooling us as well?

Anyone who has seen Farhadi’s earlier films, such as “About Elly” (2009) and “A Separation” (2011), will know how cunningly he doles out information, piece by piece. Thus, in the new movie, we gradually realize that Rahim has an ex-wife; that she will soon be married to someone else; that, while he’s been locked up, his sister Mali (Maryam Shahdaei) has been caring for his son, a shy kid with a stutter; that Farkhondeh (Sahar Goldust), a young woman beloved of Rahim, is the boy’s speech therapist; and so on. These things are true, but they are hard to cling to, because they are bundled up with things that are not necessarily true—secrets and lies, in which Rahim is all too quick to acquiesce. And the bundling only gets worse.

More here.

Omicron is so contagious that it is still flooding hospitals with sick people. And America’s continued inability to control the coronavirus has deflated its health-care system, which can no longer offer the same number of patients the same level of care. Health-care workers have quit their jobs in droves; of those who have stayed, many now can’t work, because they have Omicron breakthrough infections. “In the last two years, I’ve never known as many colleagues who have COVID as I do now,” Amanda Bettencourt, the president-elect of the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, told me. “The staffing crisis is the worst it has been through the pandemic.” This is why any comparisons between past and present hospitalization numbers are misleading: January 2021’s numbers would crush January 2022’s system because the workforce has been so diminished.

Omicron is so contagious that it is still flooding hospitals with sick people. And America’s continued inability to control the coronavirus has deflated its health-care system, which can no longer offer the same number of patients the same level of care. Health-care workers have quit their jobs in droves; of those who have stayed, many now can’t work, because they have Omicron breakthrough infections. “In the last two years, I’ve never known as many colleagues who have COVID as I do now,” Amanda Bettencourt, the president-elect of the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, told me. “The staffing crisis is the worst it has been through the pandemic.” This is why any comparisons between past and present hospitalization numbers are misleading: January 2021’s numbers would crush January 2022’s system because the workforce has been so diminished.

I’d be amazed if you couldn’t sense it—the coming end of things. A woman sits by her grandmother in a St. Louis, Miss., ICU, the older woman about to be intubated because Covid has destroyed her lungs, but until a day before she insisted that the disease wasn’t real. In Kenosha, Wisc., a young man discovers that even after murdering two men a jury will say that homicide is justified, as long as it’s against those whose politics the judge doesn’t like. Similar young men take note. Somebody’s estranged father drives to Dallas, where he waits outside of Deeley Plaza alongside hundreds of others, expecting the emergence of JFK Jr. whom he believes is coming to crown the man who lost the last presidential election. Somewhere in a Menlo Park recording studio, a dead eyed programmer with a haircut that he thinks makes him look like Caesar Augustus stares unblinkingly into a camera and announces that his Internet services will be subsumed under one meta-platform, trying to convince an exhausted, anxious, and depressed public of the piquant joys of virtual sunshine and virtual wind. At an Atlanta supermarket, a cashier who made minimum wage, politely asks a customer to wear a mask per the store’s policy; the customer leaves and returns with a gun, shooting her. She later dies.

I’d be amazed if you couldn’t sense it—the coming end of things. A woman sits by her grandmother in a St. Louis, Miss., ICU, the older woman about to be intubated because Covid has destroyed her lungs, but until a day before she insisted that the disease wasn’t real. In Kenosha, Wisc., a young man discovers that even after murdering two men a jury will say that homicide is justified, as long as it’s against those whose politics the judge doesn’t like. Similar young men take note. Somebody’s estranged father drives to Dallas, where he waits outside of Deeley Plaza alongside hundreds of others, expecting the emergence of JFK Jr. whom he believes is coming to crown the man who lost the last presidential election. Somewhere in a Menlo Park recording studio, a dead eyed programmer with a haircut that he thinks makes him look like Caesar Augustus stares unblinkingly into a camera and announces that his Internet services will be subsumed under one meta-platform, trying to convince an exhausted, anxious, and depressed public of the piquant joys of virtual sunshine and virtual wind. At an Atlanta supermarket, a cashier who made minimum wage, politely asks a customer to wear a mask per the store’s policy; the customer leaves and returns with a gun, shooting her. She later dies. WHEN POETS DIE YOUNG,

WHEN POETS DIE YOUNG, David Bennett, 57, is doing well three days after the experimental seven-hour procedure in Baltimore, doctors say. The transplant was considered the last hope of saving Mr Bennett’s life, though it is not yet clear what his long-term chances of survival are. “It was either die or do this transplant,” Mr Bennett explained a day before the surgery. “I know it’s a shot in the dark, but it’s my last choice,” he said. Doctors at the University of Maryland Medical Center were granted a special dispensation by the US medical regulator to carry out the procedure, on the basis that Mr Bennett – who has terminal heart disease – would otherwise have died.

David Bennett, 57, is doing well three days after the experimental seven-hour procedure in Baltimore, doctors say. The transplant was considered the last hope of saving Mr Bennett’s life, though it is not yet clear what his long-term chances of survival are. “It was either die or do this transplant,” Mr Bennett explained a day before the surgery. “I know it’s a shot in the dark, but it’s my last choice,” he said. Doctors at the University of Maryland Medical Center were granted a special dispensation by the US medical regulator to carry out the procedure, on the basis that Mr Bennett – who has terminal heart disease – would otherwise have died. I

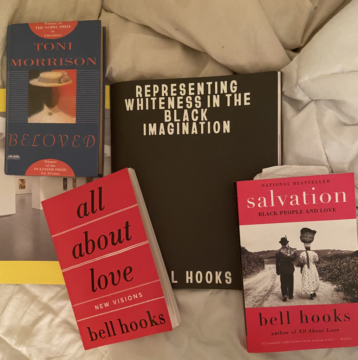

I Reading hooks transformed my thinking on a bevy of subjects, including feminism, Buddhism, Christianity, celebrity, sex, romance, and the limits and possibilities of representation. In her 2003 book We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity, she notes that “throughout our history in this nation African-Americans have had to search for images of our ancestors.” This is true of my own search for biological forebears, but in terms of intellectual heritage, I feel lucky that I didn’t have to search very far to find the images hooks conjured in words, or the actual photographs of her on dust jackets. She was incredibly prolific, and her books were everywhere when I was coming of age. Since my teens, I’ve enjoyed the slow burn of revelation that comes through encountering and reencountering her work. I’ve learned the importance of being patient enough to let meaning reach me when I’m ready for it, allowing an insight to land slowly and settle in my mind. Rereading hooks has helped me to revel in ideas without necessarily articulating them to anyone but myself, lest I interrupt the process of recognition by blabbing what I think I know too soon. As the old folks say, some things can remain private, and these reading experiences that overwrite each other and take years to develop are among the most pleasurable.

Reading hooks transformed my thinking on a bevy of subjects, including feminism, Buddhism, Christianity, celebrity, sex, romance, and the limits and possibilities of representation. In her 2003 book We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity, she notes that “throughout our history in this nation African-Americans have had to search for images of our ancestors.” This is true of my own search for biological forebears, but in terms of intellectual heritage, I feel lucky that I didn’t have to search very far to find the images hooks conjured in words, or the actual photographs of her on dust jackets. She was incredibly prolific, and her books were everywhere when I was coming of age. Since my teens, I’ve enjoyed the slow burn of revelation that comes through encountering and reencountering her work. I’ve learned the importance of being patient enough to let meaning reach me when I’m ready for it, allowing an insight to land slowly and settle in my mind. Rereading hooks has helped me to revel in ideas without necessarily articulating them to anyone but myself, lest I interrupt the process of recognition by blabbing what I think I know too soon. As the old folks say, some things can remain private, and these reading experiences that overwrite each other and take years to develop are among the most pleasurable. The presumption is that art must shock—that the violation of taboo is what gives art its charge; and that, actually, shock and the overturning of societal norms is art’s highest purpose.

The presumption is that art must shock—that the violation of taboo is what gives art its charge; and that, actually, shock and the overturning of societal norms is art’s highest purpose. In 1963, as the Beach Boys were playing on the radio and Christmas was approaching, two California schoolboys threw a coin. They were deciding who would be the guinea pig in a school science project they had designed—to beat the world record for staying awake. The lucky “winner” was Randy Gardner, a 16-year-old from San Diego. When the experiment was over, he had stayed awake for eleven days and twenty five minutes. It yielded some fundamentally important observations, fortunately recorded by William Dement, one of America’s few sleep researchers at the time. Nearly forty years later, Gardner still holds the world record—which is unlikely to be broken, as the Guinness World Records will no longer accept entries. Why? It is much too dangerous for the brain.

In 1963, as the Beach Boys were playing on the radio and Christmas was approaching, two California schoolboys threw a coin. They were deciding who would be the guinea pig in a school science project they had designed—to beat the world record for staying awake. The lucky “winner” was Randy Gardner, a 16-year-old from San Diego. When the experiment was over, he had stayed awake for eleven days and twenty five minutes. It yielded some fundamentally important observations, fortunately recorded by William Dement, one of America’s few sleep researchers at the time. Nearly forty years later, Gardner still holds the world record—which is unlikely to be broken, as the Guinness World Records will no longer accept entries. Why? It is much too dangerous for the brain. My book,

My book,  The Right to Sex has to have the cleverest title on the women’s studies shelf since Roxane Gay’s Bad Feminist. It’s bold and provocative, even a little shocking: “OK,” it seems to say, “so they’re crazy, misogynistic, and dangerous—but are those incels on to something?”

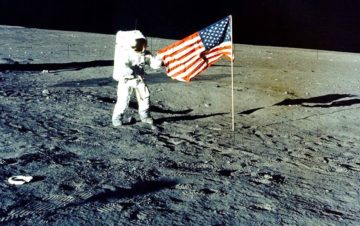

The Right to Sex has to have the cleverest title on the women’s studies shelf since Roxane Gay’s Bad Feminist. It’s bold and provocative, even a little shocking: “OK,” it seems to say, “so they’re crazy, misogynistic, and dangerous—but are those incels on to something?” Those venturing into space in 2022 have the moon in their eyes. Not that ferrying all sorts of people into orbit and suborbit will be abandoned. 2021 saw not only astronauts and scientists but also several tourists sent skyward for unmatched views of the big, blue marble that is Earth. They were young and old, women and men, various nationalities – even William Shatner, never a real spaceship captain but who played one on TV.

Those venturing into space in 2022 have the moon in their eyes. Not that ferrying all sorts of people into orbit and suborbit will be abandoned. 2021 saw not only astronauts and scientists but also several tourists sent skyward for unmatched views of the big, blue marble that is Earth. They were young and old, women and men, various nationalities – even William Shatner, never a real spaceship captain but who played one on TV. The hero of “A Hero,” the new film from Asghar Farhadi, is a sign painter and calligrapher named Rahim (Amir Jadidi). As the story begins, he leaves prison and is driven up the wall. To be precise, up a cliff of pale rock, rich in elaborate carvings, northeast of the Iranian city of Shiraz. The cliff is the home of a necropolis, Naqsh-e Rostam, and Rahim finds it covered in scaffolding; climbing high, he greets his brother-in-law, the rotund and genial Hossein (Alireza Jahandideh), who is working at the site. The wind whistles gently around them, and Hossein brews tea, close to the tomb of Xerxes the Great, a Persian king who died almost two and a half thousand years ago. Rahim, by contrast, is on a furlough for two days, after which—not unlike Eddie Murphy in “48 Hrs.” (1982)—he must return to prison. Observing the scene, you feel dizzy at the doubleness of time. It expands and contracts, either stretching far into the distance or slamming shut.

The hero of “A Hero,” the new film from Asghar Farhadi, is a sign painter and calligrapher named Rahim (Amir Jadidi). As the story begins, he leaves prison and is driven up the wall. To be precise, up a cliff of pale rock, rich in elaborate carvings, northeast of the Iranian city of Shiraz. The cliff is the home of a necropolis, Naqsh-e Rostam, and Rahim finds it covered in scaffolding; climbing high, he greets his brother-in-law, the rotund and genial Hossein (Alireza Jahandideh), who is working at the site. The wind whistles gently around them, and Hossein brews tea, close to the tomb of Xerxes the Great, a Persian king who died almost two and a half thousand years ago. Rahim, by contrast, is on a furlough for two days, after which—not unlike Eddie Murphy in “48 Hrs.” (1982)—he must return to prison. Observing the scene, you feel dizzy at the doubleness of time. It expands and contracts, either stretching far into the distance or slamming shut. Over at the podcast Myself With Others:

Over at the podcast Myself With Others: Suzanne Schneider in Late Light:

Suzanne Schneider in Late Light: