Christopher de Bellaigue in The Guardian:

For the past 12 weeks, revolutionary sentiment has been coursing through the cities and towns of the Persian plateau. The agitation was triggered by the death of Mahsa Amini, a young Kurdish woman, on 16 September after she was arrested by the morality police in Tehran. From the outset the movement had a feminist character, but it has also united citizens of different classes and ethnicities around a shared desire to see the back of the Islamic Republic. Iran has known numerous protest movements over the past decade and a half, and the nation’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has comfortably suppressed each one with a combination of severity and deft exploitation of divisions within the opposition. This time, however, the resilience and unity shown by the regime’s opponents have consigned the old pattern of episodic unrest to the past. Iran has entered a period of rolling protest in which the Islamic Republic must defend itself against wave upon wave of public anger.

For the past 12 weeks, revolutionary sentiment has been coursing through the cities and towns of the Persian plateau. The agitation was triggered by the death of Mahsa Amini, a young Kurdish woman, on 16 September after she was arrested by the morality police in Tehran. From the outset the movement had a feminist character, but it has also united citizens of different classes and ethnicities around a shared desire to see the back of the Islamic Republic. Iran has known numerous protest movements over the past decade and a half, and the nation’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has comfortably suppressed each one with a combination of severity and deft exploitation of divisions within the opposition. This time, however, the resilience and unity shown by the regime’s opponents have consigned the old pattern of episodic unrest to the past. Iran has entered a period of rolling protest in which the Islamic Republic must defend itself against wave upon wave of public anger.

In their retaliation against the protesters, the security forces have killed at least 448 people, including 60 children and 29 women, and made up to 17,000 arrests.

More here.

Bell’s palsy is a neurological condition resulting from damage to the seventh cranial nerve, and typified by partial facial paralysis and pain on one side of the head.

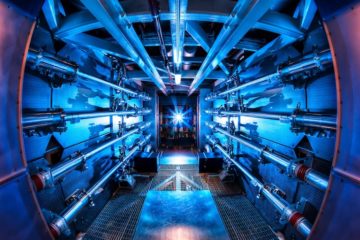

Bell’s palsy is a neurological condition resulting from damage to the seventh cranial nerve, and typified by partial facial paralysis and pain on one side of the head. Existing nuclear power plants work through fission — splitting apart heavy atoms to create energy. In fission, a neutron collides with a heavy uranium atom, splitting it into lighter atoms and releasing a lot of heat and energy at the same time. Fusion, on the other hand, works in the opposite way — it involves smushing two atoms (often two hydrogen atoms) together to create a new element (often helium), in the same way that stars creates energy. In that process, the two hydrogen atoms lose a small amount of mass, which is converted to energy according to Einstein’s famous equation, E=mc². Because the speed of light is very, very fast — 300,000,000 meters per second — even a tiny amount of mass lost can result in a ton of energy.

Existing nuclear power plants work through fission — splitting apart heavy atoms to create energy. In fission, a neutron collides with a heavy uranium atom, splitting it into lighter atoms and releasing a lot of heat and energy at the same time. Fusion, on the other hand, works in the opposite way — it involves smushing two atoms (often two hydrogen atoms) together to create a new element (often helium), in the same way that stars creates energy. In that process, the two hydrogen atoms lose a small amount of mass, which is converted to energy according to Einstein’s famous equation, E=mc². Because the speed of light is very, very fast — 300,000,000 meters per second — even a tiny amount of mass lost can result in a ton of energy.

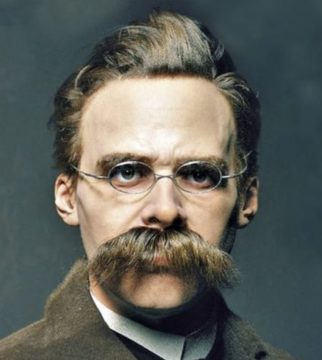

Should one be altruistic and act for the sake of others, even at a cost to oneself? Should one’s actions be free of any egoistic motivations? Is selflessness a virtue one ought to strive for and cultivate? To many of us the answer to such questions is so self-evident that even raising them would appear to be either a sign of moral obtuseness or an infantile attempt at provocation. For Friedrich Nietzsche, the 19th Century “immoralist” German philosopher, however, the answer to these questions was by no means straightforward and unequivocal. Rather, he believed that altruism and selflessness are neither virtues to be unconditionally pursued and celebrated nor obligations grounded in absolute morality. Moreover, he thought that other-regard (regard for others) is something to be practiced, if at all, with care and moderation; indeed, in some cases selflessness could pose a great danger or even be a sign of deep existential malaise.

Should one be altruistic and act for the sake of others, even at a cost to oneself? Should one’s actions be free of any egoistic motivations? Is selflessness a virtue one ought to strive for and cultivate? To many of us the answer to such questions is so self-evident that even raising them would appear to be either a sign of moral obtuseness or an infantile attempt at provocation. For Friedrich Nietzsche, the 19th Century “immoralist” German philosopher, however, the answer to these questions was by no means straightforward and unequivocal. Rather, he believed that altruism and selflessness are neither virtues to be unconditionally pursued and celebrated nor obligations grounded in absolute morality. Moreover, he thought that other-regard (regard for others) is something to be practiced, if at all, with care and moderation; indeed, in some cases selflessness could pose a great danger or even be a sign of deep existential malaise.

This century has not been kind to human-rights optimists, with 2022 being no exception. Many gains in the recognition and protection of the universal rights recognized in the post-World War II and post-Cold War years have stalled or been eroded. Russia’s criminal behavior in Ukraine is but the most recent example of a broader trend – made even more shocking by Russia’s status as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, which exists to uphold the very principles of international law that the Kremlin is now so brazenly violating.

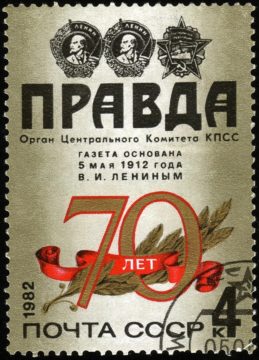

This century has not been kind to human-rights optimists, with 2022 being no exception. Many gains in the recognition and protection of the universal rights recognized in the post-World War II and post-Cold War years have stalled or been eroded. Russia’s criminal behavior in Ukraine is but the most recent example of a broader trend – made even more shocking by Russia’s status as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, which exists to uphold the very principles of international law that the Kremlin is now so brazenly violating. My everyday experiences as a chemistry professor at an American university in 2021 bring back memories from my school and university time in the USSR. Not good memories—more like Orwellian nightmares. I will compare my past and present experiences to illustrate the following parallels between the USSR and the US today: (i) the atmosphere of fear and self-censorship; (ii) the omnipresence of ideology (focusing on examples from science); (iii) an intolerance of dissenting opinions (i.e., suppression of ideas and people, censorship, and Newspeak); (iv) the use of social engineering to solve real and imagined problems.

My everyday experiences as a chemistry professor at an American university in 2021 bring back memories from my school and university time in the USSR. Not good memories—more like Orwellian nightmares. I will compare my past and present experiences to illustrate the following parallels between the USSR and the US today: (i) the atmosphere of fear and self-censorship; (ii) the omnipresence of ideology (focusing on examples from science); (iii) an intolerance of dissenting opinions (i.e., suppression of ideas and people, censorship, and Newspeak); (iv) the use of social engineering to solve real and imagined problems. Moheb Costandi’s title is taken from Nietzsche’s philosophical masterpiece Thus Spoke Zarathustra: “The awakened and knowing say: body am I entirely, and nothing more; and soul is only the name for something about the body.” The radical rejection of mind-body dualism expressed in this sentence is shared today by most neuroscientists, who believe that the mind is a product of the brain. Indeed, this “neurocentric” view has been widely accepted and, writes Costandi, “the idea that we are our brains is now firmly established”.

Moheb Costandi’s title is taken from Nietzsche’s philosophical masterpiece Thus Spoke Zarathustra: “The awakened and knowing say: body am I entirely, and nothing more; and soul is only the name for something about the body.” The radical rejection of mind-body dualism expressed in this sentence is shared today by most neuroscientists, who believe that the mind is a product of the brain. Indeed, this “neurocentric” view has been widely accepted and, writes Costandi, “the idea that we are our brains is now firmly established”. The official campaign for the 2024 Republican Presidential nomination is barely three weeks old, but there is one clear takeaway so far:

The official campaign for the 2024 Republican Presidential nomination is barely three weeks old, but there is one clear takeaway so far:  David Waldstreicher in Boston Review:

David Waldstreicher in Boston Review: Katherine Franke in The Nation (Photo by Jim Watson / AFP via Getty Images):

Katherine Franke in The Nation (Photo by Jim Watson / AFP via Getty Images):

Mona Ali , Anna Gelpern, Avinash Persaud, Rishikesh Ram Bhandary, Brad Setser, and Adam Tooze in Phenomenal World’s The Polycrisis:

Mona Ali , Anna Gelpern, Avinash Persaud, Rishikesh Ram Bhandary, Brad Setser, and Adam Tooze in Phenomenal World’s The Polycrisis: T

T