Ode to the Soccer Ball Sailing Over a

Barbed-Wire Fence

…….. Tornillo. Has become the symbol of what may be the longest U.S. mass

……. detention of children not charged with crimes since the World War II

…….. internment of Japanese Americans. —Robert Moore, Texas Monthly

Praise Tornillo: word for screw in Spanish, word for jailer in English,

word for three thousand adolescent migrants incarcerated in a camp.

Praise the three thousand soccer balls gift-wrapped at Christmas,

as if raindrops in the desert inflated and bounced through the door.

Priase the soccer games rotating with a whistle every twenty minutes,

so three thousand adolescent migrants could take turns kicking a ball.

Priase the boys and girls who walked a thousand miles, blood caked

in their toes, yelling in Spanish and a dozen Mayan tongues on the field.

Praise the first teenager, brain ablaze like chili pepper Christmas lights,

to kick a soccer ball high over the chain-link and barbed wire-fence.

Praise the first teenager to scrawl a name and number on the face

of the ball, then boot it all the way to the dirt road on the other side.

Praise the smirk of teenagers at the jailer scooping up fugitive

soccer balls, jabbering about the ingratitude of teenagers at Christmas.

Praise the soccer ball sailing over the barbed-wire fence, white

and black like the moon, yellow like the sun, blue like the world.

Praise the soccer ball fling to the moon, flying to the sun, flying to other

worlds, flying to Antigua, where Starbucks buys coffee beans.

Praise the soccer ball bounding off the lawn at the White House,

thudding off the president’s head as he waves to absolutely no one.

Praise the piñata of the president’s head jellybeans pouring from his ears,

enough to feed three thousand adolescents incarcerated at Tornillo.

Praise Tornillo: word in spanish for adolescent migrant internment camp,

abandoned by jailers in the desert, liberated by a blizzard of soccer balls.

by Martín Espada

from Floaters

W.W. Norton, 2021

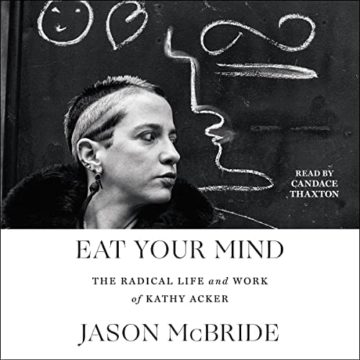

Kathy Acker — proto-punk, tough-stemmed flower, ransacker of texts, literary heir to William S. Burroughs and Gertrude Stein, sex worker, loather of establishments, striver for maximum impudence — was born into a soft life on Manhattan’s East Side in 1947.

Kathy Acker — proto-punk, tough-stemmed flower, ransacker of texts, literary heir to William S. Burroughs and Gertrude Stein, sex worker, loather of establishments, striver for maximum impudence — was born into a soft life on Manhattan’s East Side in 1947.

The Irish writer Gavin McCrea was supposed to be writing the third in a loose trilogy of novels about the development of communism, following

The Irish writer Gavin McCrea was supposed to be writing the third in a loose trilogy of novels about the development of communism, following  A study surveying more than 3.4 million people has found nearly 4,000 genetic variants related to the use of alcohol and tobacco, scientists reported Wednesday (Dec 7) in

A study surveying more than 3.4 million people has found nearly 4,000 genetic variants related to the use of alcohol and tobacco, scientists reported Wednesday (Dec 7) in  Artificial intelligence (AI) is

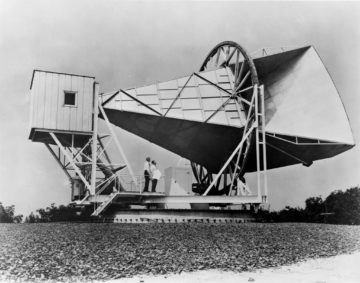

Artificial intelligence (AI) is  I was recently reading an old article by string theorist Robbert Dijkgraaf in Quanta Magazine entitled “

I was recently reading an old article by string theorist Robbert Dijkgraaf in Quanta Magazine entitled “ In the orthodox telling, there was only one revolution that mattered, after all. The fact that American revolutionaries won their independence in part because the French intervened in their British civil war has often been narrated as at most a useful irony. Certainly Africans or Natives had nothing to do with it, except as desperate fighters for their own marginal purposes: defined out of the story partly because they lost but mostly because, well, they were defined out of the story. Yet the century-long debate between “Progressive” (read: radical) versus “Whig” (liberal and conservative) historians about whether ordinary white people benefitted or whether elites did has begun to seem almost beside the point: there was more at stake for others than republicanism or nationhood.

In the orthodox telling, there was only one revolution that mattered, after all. The fact that American revolutionaries won their independence in part because the French intervened in their British civil war has often been narrated as at most a useful irony. Certainly Africans or Natives had nothing to do with it, except as desperate fighters for their own marginal purposes: defined out of the story partly because they lost but mostly because, well, they were defined out of the story. Yet the century-long debate between “Progressive” (read: radical) versus “Whig” (liberal and conservative) historians about whether ordinary white people benefitted or whether elites did has begun to seem almost beside the point: there was more at stake for others than republicanism or nationhood. The trip to

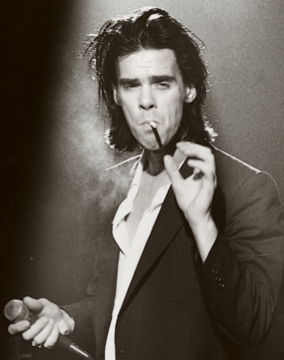

The trip to  The former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, recently selected Faith, Hope and Carnage as his New Statesman

The former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, recently selected Faith, Hope and Carnage as his New Statesman  The oldest DNA ever recovered has revealed a remarkable two-million-year-old ecosystem in Greenland, including the presence of an unlikely explorer: the mastodon.

The oldest DNA ever recovered has revealed a remarkable two-million-year-old ecosystem in Greenland, including the presence of an unlikely explorer: the mastodon. Why is april

Why is april

The medieval bubonic plague pandemic was a major historical event. But what happened next? To give myself some grounding on this topic, I previously reviewed

The medieval bubonic plague pandemic was a major historical event. But what happened next? To give myself some grounding on this topic, I previously reviewed  The Congressional decision to

The Congressional decision to