Philip Ball in The Guardian:

There are plenty of uncertainties and unknowns around fusion energy, but on this question we can be clear. Since what we do about carbon emissions in the next two or three decades is likely to determine whether the planet gets just uncomfortably or catastrophically warmer by the end of the century, then the answer is no: fusion won’t come to our rescue. But if we can somehow scramble through the coming decades with makeshift ways of keeping a lid on global heating, there’s good reason to think that in the second half of the century fusion power plants will gradually help rebalance the energy economy.

There are plenty of uncertainties and unknowns around fusion energy, but on this question we can be clear. Since what we do about carbon emissions in the next two or three decades is likely to determine whether the planet gets just uncomfortably or catastrophically warmer by the end of the century, then the answer is no: fusion won’t come to our rescue. But if we can somehow scramble through the coming decades with makeshift ways of keeping a lid on global heating, there’s good reason to think that in the second half of the century fusion power plants will gradually help rebalance the energy economy.

Perhaps it’s this wish for a quick fix that drives some of the hype with which advances in fusion science and technology are plagued. Take the announcement last December of a “major breakthrough” by the National Ignition Facility (NIF) of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California. The NIF team reported that, in their efforts to develop a somewhat unorthodox form of fusion called inertial confinement fusion (ICF), they had produced more energy in their reaction chamber than they had put in to get the fusion process under way.

More here.

All animals, plants, fungi and protists — which collectively make up the domain of life called eukaryotes — have genomes with a peculiar feature that has puzzled researchers for almost half a century: Their genes are fragmented.

All animals, plants, fungi and protists — which collectively make up the domain of life called eukaryotes — have genomes with a peculiar feature that has puzzled researchers for almost half a century: Their genes are fragmented. Postcards from Absurdistan is the third volume in a ‘loose trilogy of cultural histories’ in which Derek Sayer has argued that European modernity is best examined from a vantage point located, both literally and figuratively, in Bohemia and its capital, Prague. The first volume, The Coasts of Bohemia (1998), tackled the issue of national identity. It presented Czech history – from its mythic beginnings to just after the communist takeover in 1948 – as a lesson on the nature of national historiography. When a ‘small’ nation has, for most of its past, struggled for recognition, its history is bound to consist of attempts to re-invent the past in order to assure itself of a future. The form of this reassurance: a bricolage of national treasures assembled largely under the motto ‘small but ours’. Focusing on the main tropes of the Czech National Revival – especially the emphasis on the Czech language as the basis for national identity, and the encoding of Czechness as something anti-German, anti-aristocratic and anti-Catholic – Sayer presents this chequered history as a corrective to the national histories of bigger, older, more secure nations. A lot of what he marks out as specifically Czech, however, sounds very familiar in the Irish context. None better than the Czechs at understanding Irish people’s fondness for the ‘best little country in the world’ trope (including its associated ironies) and the pitfalls of turning a language into a crux of nationality.

Postcards from Absurdistan is the third volume in a ‘loose trilogy of cultural histories’ in which Derek Sayer has argued that European modernity is best examined from a vantage point located, both literally and figuratively, in Bohemia and its capital, Prague. The first volume, The Coasts of Bohemia (1998), tackled the issue of national identity. It presented Czech history – from its mythic beginnings to just after the communist takeover in 1948 – as a lesson on the nature of national historiography. When a ‘small’ nation has, for most of its past, struggled for recognition, its history is bound to consist of attempts to re-invent the past in order to assure itself of a future. The form of this reassurance: a bricolage of national treasures assembled largely under the motto ‘small but ours’. Focusing on the main tropes of the Czech National Revival – especially the emphasis on the Czech language as the basis for national identity, and the encoding of Czechness as something anti-German, anti-aristocratic and anti-Catholic – Sayer presents this chequered history as a corrective to the national histories of bigger, older, more secure nations. A lot of what he marks out as specifically Czech, however, sounds very familiar in the Irish context. None better than the Czechs at understanding Irish people’s fondness for the ‘best little country in the world’ trope (including its associated ironies) and the pitfalls of turning a language into a crux of nationality. A Vindication was written in six weeks. On January 3, 1792, the day she gave the last sheet to the printer, Wollstonecraft wrote to Roscoe: “I am dissatisfied with myself for not having done justice to the subject.—Do not suspect me of false modesty—I mean to say that had I allowed myself more time I could have written a better book, in every sense of the word.” Wollstonecraft isn’t in fact being coy: her book isn’t well-made. Her main arguments about education are at the back, the middle is a sarcastic roasting of male conduct-book writers in the style of her attack on Burke, and the parts about marriage and friendship are scattered throughout when they would have more impact in one place. There is a moralizing, bossy tone, noticeably when Wollstonecraft writes about the sorts of women she doesn’t like (flirts and rich women: take a deep breath). It ends with a plea to men, in a faux-religious style that doesn’t play to her strengths as a writer. In this, her book is like many landmark feminist books—The Second Sex, The Feminine Mystique—that are part essay, part argument, part memoir, held together by some force, it seems, that is attributable solely to its writer. It’s as if these books, to be written at all, have to be brought into being by autodidacts who don’t know for sure what they’re doing—just that they have to do it.

A Vindication was written in six weeks. On January 3, 1792, the day she gave the last sheet to the printer, Wollstonecraft wrote to Roscoe: “I am dissatisfied with myself for not having done justice to the subject.—Do not suspect me of false modesty—I mean to say that had I allowed myself more time I could have written a better book, in every sense of the word.” Wollstonecraft isn’t in fact being coy: her book isn’t well-made. Her main arguments about education are at the back, the middle is a sarcastic roasting of male conduct-book writers in the style of her attack on Burke, and the parts about marriage and friendship are scattered throughout when they would have more impact in one place. There is a moralizing, bossy tone, noticeably when Wollstonecraft writes about the sorts of women she doesn’t like (flirts and rich women: take a deep breath). It ends with a plea to men, in a faux-religious style that doesn’t play to her strengths as a writer. In this, her book is like many landmark feminist books—The Second Sex, The Feminine Mystique—that are part essay, part argument, part memoir, held together by some force, it seems, that is attributable solely to its writer. It’s as if these books, to be written at all, have to be brought into being by autodidacts who don’t know for sure what they’re doing—just that they have to do it. Perhaps it took the roiling events that would give such a manic-depressive quality to 1963––the death in early June of Pope John XXIII (and with it, some feared, the demise of John’s policy of aggiornamento, “updating”); the signing of the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in August; the March on Washington the same month; and, in cruel culmination of the year’s roller-coaster ride, the assassination of President Kennedy on November 22––to open the ears (and hearts) of the American public, by year’s end emotionally spent, to the cheeky wit and fresh take on rock ‘n’ roll offered by the Beatles. As Rorem would observe, “Our need for [the Beatles] is…specifically a renewal, a renewal of pleasure.”

Perhaps it took the roiling events that would give such a manic-depressive quality to 1963––the death in early June of Pope John XXIII (and with it, some feared, the demise of John’s policy of aggiornamento, “updating”); the signing of the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in August; the March on Washington the same month; and, in cruel culmination of the year’s roller-coaster ride, the assassination of President Kennedy on November 22––to open the ears (and hearts) of the American public, by year’s end emotionally spent, to the cheeky wit and fresh take on rock ‘n’ roll offered by the Beatles. As Rorem would observe, “Our need for [the Beatles] is…specifically a renewal, a renewal of pleasure.” Thanks so much for speaking to us Nick, I wanted to start off by asking about the philosophical principles you use in the lab every day. Philosophers often see science as proposing a reductive theory of the world, breaking it down into its constituent parts. Some worry that this ignores the complexity of life. Do you think that this reduction plays a role in your work and science more broadly?

Thanks so much for speaking to us Nick, I wanted to start off by asking about the philosophical principles you use in the lab every day. Philosophers often see science as proposing a reductive theory of the world, breaking it down into its constituent parts. Some worry that this ignores the complexity of life. Do you think that this reduction plays a role in your work and science more broadly? While battles about what’s called the “woke left” now dominate political discussion in many countries, it’s time to ask whether woke really belongs on the left—or if woke represents a distortion of the core principles of the left, a drift into a philosophy of tribalism.

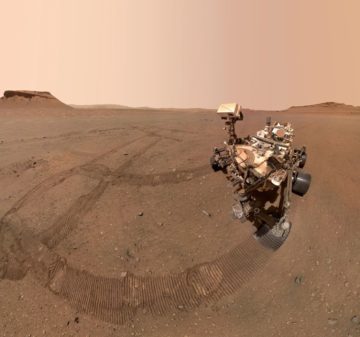

While battles about what’s called the “woke left” now dominate political discussion in many countries, it’s time to ask whether woke really belongs on the left—or if woke represents a distortion of the core principles of the left, a drift into a philosophy of tribalism. For decades, scientists who study Mars have watched in envy as spacecraft brought pieces of the Moon, chunks of asteroids and even samples of the solar wind to Earth to be studied. Now some of those researchers might finally be on track to receive rocks from the red planet — but only if NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) can pull off a complex and daring mission.

For decades, scientists who study Mars have watched in envy as spacecraft brought pieces of the Moon, chunks of asteroids and even samples of the solar wind to Earth to be studied. Now some of those researchers might finally be on track to receive rocks from the red planet — but only if NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) can pull off a complex and daring mission. “Our Latin American literature has always been a committed, a responsible literature,” explained Guatemalan novelist Miguel Ángel Asturias in 1973.

“Our Latin American literature has always been a committed, a responsible literature,” explained Guatemalan novelist Miguel Ángel Asturias in 1973. Drug overdose deaths have

Drug overdose deaths have  As an insider observing this food fight, it is surreal to watch reporters and commentators promote the narrative that the government’s Likud-Jewish Power-Religious Zionism coalition and the Supreme Court exist on extreme opposing ends of the political spectrum. Their differences, when it comes to how they rule over the lives of Palestinians, are purely cosmetic. In essence, one camp wants to eat with their hands while the other wants to mandate forks and knives, but in both scenarios, Palestinian rights will be devoured.

As an insider observing this food fight, it is surreal to watch reporters and commentators promote the narrative that the government’s Likud-Jewish Power-Religious Zionism coalition and the Supreme Court exist on extreme opposing ends of the political spectrum. Their differences, when it comes to how they rule over the lives of Palestinians, are purely cosmetic. In essence, one camp wants to eat with their hands while the other wants to mandate forks and knives, but in both scenarios, Palestinian rights will be devoured. On the sunny first day of seminar, I sat at the end of a pair of picnic tables with nervous, excited 17-year-olds. Twelve high-school students had been chosen by the Telluride Association through a rigorous application process—the acceptance rate is reportedly around 3 percent—to spend six weeks together taking a college-level course, all expenses paid.

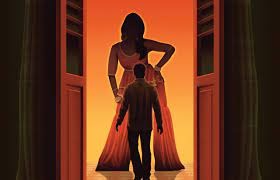

On the sunny first day of seminar, I sat at the end of a pair of picnic tables with nervous, excited 17-year-olds. Twelve high-school students had been chosen by the Telluride Association through a rigorous application process—the acceptance rate is reportedly around 3 percent—to spend six weeks together taking a college-level course, all expenses paid. Trying to sort out who is who, and what everybody wants, is no easy task in “Joyland,” a début feature from the Pakistani director Saim Sadiq. In Lahore, a woman named Nucchi (Sarwat Gilani), who already has three daughters, remarks that her water has broken; she might as well be announcing that dinner is served. For the birth of her fourth child, she is ferried to hospital on the back of a moped driven by Haider (Ali Junejo), whom we take to be her husband. Not so. He is, in fact, the brother of her husband, Saleem (Sameer Sohail). Haider is married to Mumtaz (Rasti Farooq); they have no offspring, to the dismay of his aged father, known as Abba (Salmaan Peerzada). All of the above inhabit one household. It’s not a peaceful place, or an especially happy one, but it’s home.

Trying to sort out who is who, and what everybody wants, is no easy task in “Joyland,” a début feature from the Pakistani director Saim Sadiq. In Lahore, a woman named Nucchi (Sarwat Gilani), who already has three daughters, remarks that her water has broken; she might as well be announcing that dinner is served. For the birth of her fourth child, she is ferried to hospital on the back of a moped driven by Haider (Ali Junejo), whom we take to be her husband. Not so. He is, in fact, the brother of her husband, Saleem (Sameer Sohail). Haider is married to Mumtaz (Rasti Farooq); they have no offspring, to the dismay of his aged father, known as Abba (Salmaan Peerzada). All of the above inhabit one household. It’s not a peaceful place, or an especially happy one, but it’s home. “Barbara Kassel”s evocative paintings explore the passage of time. From her loft in New York City, she paints interior and exterior views, creating a visual diary of daily life. Working with oil on panel, the smooth surfaces are meticulously rendered serene scenes. Warm reds and yellow embrace cooler blues and grays and invite the viewer into the large-scale works. Kassel describes the paintings in part biographical and instinctually narrative. Carefully exploring the world around her, she mixes observation and invention as she captures fleeting moments in time.”

“Barbara Kassel”s evocative paintings explore the passage of time. From her loft in New York City, she paints interior and exterior views, creating a visual diary of daily life. Working with oil on panel, the smooth surfaces are meticulously rendered serene scenes. Warm reds and yellow embrace cooler blues and grays and invite the viewer into the large-scale works. Kassel describes the paintings in part biographical and instinctually narrative. Carefully exploring the world around her, she mixes observation and invention as she captures fleeting moments in time.”