Rafia Zakaria in The Baffler:

THERE IS, EASILY FOUND on the internet, a photograph of the writer Kingsley Amis relaxing on a beach with his back to the camera. Written in lipstick on his back are the words “1 fat Englishman. I fuck anything.” The words are the handiwork of his then wife Hilly, who had learned that her husband was having an affair with fashion model Elizabeth Jane Howard. Howard would eventually become the writer’s wife, the two of them having fallen in love during the inaugural Cheltenham literary festival that Amis had attended (and Howard had directed).

THERE IS, EASILY FOUND on the internet, a photograph of the writer Kingsley Amis relaxing on a beach with his back to the camera. Written in lipstick on his back are the words “1 fat Englishman. I fuck anything.” The words are the handiwork of his then wife Hilly, who had learned that her husband was having an affair with fashion model Elizabeth Jane Howard. Howard would eventually become the writer’s wife, the two of them having fallen in love during the inaugural Cheltenham literary festival that Amis had attended (and Howard had directed).

Having won the spot beside this literary genius was a dubious blessing. Howard, who had written three novels of her own before ever meeting the author who made his reputation with the publication of Lucky Jim in 1954 (and who in 1963 published One Fat Englishman), found herself running a large household revolving around the lone star of Amis. She stopped writing, took to cooking elaborate meals, juggling the schedule of Amis’s two sons to whom she was stepmother and a thousand other necessary tasks. As recounted in Carmela Ciuraru’s recent book Lives of the Wives: Five Literary Marriages, Howard was often so very tired that she would fall asleep sitting upright in a chair in the evening. With this capable woman at his side, Amis continued his writing career having changed out the wife he had procured at Oxford for a prettier new model.

More here.

Poornima Paidipaty interviews Pranab Bardhan in Phenomenal World:

Poornima Paidipaty interviews Pranab Bardhan in Phenomenal World: Sophus Helle in Aeon:

Sophus Helle in Aeon: I

I In 1955 Henry Pleasants, a critic of both popular and classical music, issued a cranky screed of a book, “The Agony of Modern Music,” which opened with the implacable verdict that “serious music is a dead art.” Pleasants’s thesis was that the traditional forms of classical music — opera, oratorio, orchestral and chamber music, all constructions of a bygone era — no longer related to the experience of our modern lives. Composers had lost touch with the currents of popular taste, and popular music, with its vitality and its connection to the spirit of the times, had dethroned the classics. Absent the mass appeal enjoyed by past masters like Beethoven, Verdi, Wagner and Tchaikovsky, modern composers had retreated into obscurantism, condemned to a futile search for novelty amid the detritus of a tradition that was, like overworked soil, exhausted and fallow. One could still love classical music, but only with the awareness that it was a relic of the past and in no way representative of our contemporary experience.

In 1955 Henry Pleasants, a critic of both popular and classical music, issued a cranky screed of a book, “The Agony of Modern Music,” which opened with the implacable verdict that “serious music is a dead art.” Pleasants’s thesis was that the traditional forms of classical music — opera, oratorio, orchestral and chamber music, all constructions of a bygone era — no longer related to the experience of our modern lives. Composers had lost touch with the currents of popular taste, and popular music, with its vitality and its connection to the spirit of the times, had dethroned the classics. Absent the mass appeal enjoyed by past masters like Beethoven, Verdi, Wagner and Tchaikovsky, modern composers had retreated into obscurantism, condemned to a futile search for novelty amid the detritus of a tradition that was, like overworked soil, exhausted and fallow. One could still love classical music, but only with the awareness that it was a relic of the past and in no way representative of our contemporary experience. My childhood Barbies were always in trouble. I was constantly giving them diagnoses of rare diseases, performing risky surgeries to cure them, or else kidnapping them—jamming them into the deepest reaches of my closet, without plastic food or plastic water, so they could be saved again, returned to their plastic doll-cakes and their slightly-too-small wooden home. (My mother had drawn her lines in the sand; we had no Dreamhouse.) My abusive behavior was nothing special. Most girls I know liked to mess their Barbies up; and when it comes to child’s play, crisis is hardly unusual. It’s a way to make sense of the thrills and terrors of autonomy, the problem of other people’s desires, the brute force of parental disapproval. But there was something about Barbie that especially demanded crisis: her perfection. That’s why Barbie needed to have a special kind of surgery; why she was dying; why she was in danger. She was too flawless, something had to be wrong. I treated Barbie the way a mother with

My childhood Barbies were always in trouble. I was constantly giving them diagnoses of rare diseases, performing risky surgeries to cure them, or else kidnapping them—jamming them into the deepest reaches of my closet, without plastic food or plastic water, so they could be saved again, returned to their plastic doll-cakes and their slightly-too-small wooden home. (My mother had drawn her lines in the sand; we had no Dreamhouse.) My abusive behavior was nothing special. Most girls I know liked to mess their Barbies up; and when it comes to child’s play, crisis is hardly unusual. It’s a way to make sense of the thrills and terrors of autonomy, the problem of other people’s desires, the brute force of parental disapproval. But there was something about Barbie that especially demanded crisis: her perfection. That’s why Barbie needed to have a special kind of surgery; why she was dying; why she was in danger. She was too flawless, something had to be wrong. I treated Barbie the way a mother with  It has been a hundred years since D.H. Lawrence published “Studies in Classic American Literature,” and in the annals of literary criticism the book may still claim the widest discrepancy between title and content.

It has been a hundred years since D.H. Lawrence published “Studies in Classic American Literature,” and in the annals of literary criticism the book may still claim the widest discrepancy between title and content. It’s 1965. Truman Capote was a known figure on the literary scene and a member of the global social jet set. His bestselling books Other Voices, Other Rooms and Breakfast at Tiffany’s had made him a literary favorite. And after five years of painstaking research, and gut-wrenching personal investment, part I of In Cold Blood debuted in The New Yorker. As people across the country opened their magazines and read the first lines of the story, they were riveted. Overnight, Capote catapulted from a mere darling of the literary world to a full-fledged global celebrity on a par with the likes of rockstars and film legends.

It’s 1965. Truman Capote was a known figure on the literary scene and a member of the global social jet set. His bestselling books Other Voices, Other Rooms and Breakfast at Tiffany’s had made him a literary favorite. And after five years of painstaking research, and gut-wrenching personal investment, part I of In Cold Blood debuted in The New Yorker. As people across the country opened their magazines and read the first lines of the story, they were riveted. Overnight, Capote catapulted from a mere darling of the literary world to a full-fledged global celebrity on a par with the likes of rockstars and film legends. Mainframe computers are often seen as ancient machines—practically dinosaurs. But mainframes, which are purpose-built to process enormous amounts of data, are still extremely relevant today. If they’re dinosaurs, they’re T-Rexes, and desktops and server computers are puny mammals to be trodden underfoot.

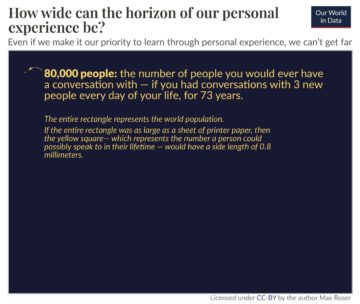

Mainframe computers are often seen as ancient machines—practically dinosaurs. But mainframes, which are purpose-built to process enormous amounts of data, are still extremely relevant today. If they’re dinosaurs, they’re T-Rexes, and desktops and server computers are puny mammals to be trodden underfoot. It’s tempting to believe that we can simply rely on personal experience to develop our understanding of the world. But that’s a mistake. The world is large, and we can experience only very little of it personally. To see what the world is like, we need to rely on other means: carefully-collected global statistics.

It’s tempting to believe that we can simply rely on personal experience to develop our understanding of the world. But that’s a mistake. The world is large, and we can experience only very little of it personally. To see what the world is like, we need to rely on other means: carefully-collected global statistics. When I finally did leave the sex trade after finishing my bachelor’s degree as a mature student, I spent seven years working in “good” jobs in the corporate sector. This meant, as I understood it, that I didn’t work nights, that I was a salaried employee, and that I had dental benefits. I had a shiny access card that opened doors—to a gleaming, marble elevator bank, to planters full of plastic ferns, to blocks of cubicles illuminated by fluorescent lighting, a land of perpetual daytime.

When I finally did leave the sex trade after finishing my bachelor’s degree as a mature student, I spent seven years working in “good” jobs in the corporate sector. This meant, as I understood it, that I didn’t work nights, that I was a salaried employee, and that I had dental benefits. I had a shiny access card that opened doors—to a gleaming, marble elevator bank, to planters full of plastic ferns, to blocks of cubicles illuminated by fluorescent lighting, a land of perpetual daytime. She was not beautiful, but she looked like she was. She was practically famous for it in the cloistered social universe of the liberal arts college where I had just arrived. Women whispered about her effortless elegance in the bathrooms at parties, and a man who had dated her for a summer informed me, with the dispassionate assurance of a connoisseur, that she was the hottest girl on campus. The skier who brazenly dozed in Introduction to Philosophy each morning intimated between snores that she looked like Uma Thurman, whom she did not resemble in the least. I knew this even though I had yet to see her for myself, because I had done what anyone with an appetite for truth and beauty would do in 2011, besides enroll in Introduction to Philosophy: I had studied her profile on Facebook—and discovered, much to my surprise and chagrin, an entirely average-looking person, slightly hunched, with a mop of mousy hair.

She was not beautiful, but she looked like she was. She was practically famous for it in the cloistered social universe of the liberal arts college where I had just arrived. Women whispered about her effortless elegance in the bathrooms at parties, and a man who had dated her for a summer informed me, with the dispassionate assurance of a connoisseur, that she was the hottest girl on campus. The skier who brazenly dozed in Introduction to Philosophy each morning intimated between snores that she looked like Uma Thurman, whom she did not resemble in the least. I knew this even though I had yet to see her for myself, because I had done what anyone with an appetite for truth and beauty would do in 2011, besides enroll in Introduction to Philosophy: I had studied her profile on Facebook—and discovered, much to my surprise and chagrin, an entirely average-looking person, slightly hunched, with a mop of mousy hair.