T. J. Clark in The Nation:

T. J. Clark in The Nation:

What goes into the making of a movie? By “movie,” in Pasolini’s case, I take it that we mean a distinctive, unprecedented, unforgettable way of seeing, in which the world is turned toward us and shown in a new light. And the new light is not merely glittering and irresistible (though in Pasolini it is regularly both) but necessary. Necessary to its subject: in this instance, in the films Pasolini made in the early 1960s, the face and temper and desperation—the disintegrating identity—of the proletariat as the long epic of class struggle drew to an end.

What goes into such a moment of form—such a making of a style? I summon up a memory from near the beginning of Accattone, whose opening sequences are stamped on my mind—or his choice of distance between moving face and moving camera, his unforgiving lighting, his shallow depth of focus, the brittle staccato of his soundtrack. Start almost anywhere in these early movies, or in the scenes from Fellini’s Notte di Cabiria where Pasolini’s imprint is unmistakable; open a page at random in The Ragazzi or A Violent Life or A Night on the Tram; and immediately you are in a working-class world that very few others have touched. A savage and absolute grandeur greets you, tinged with (undercut by) bitterness and compassion, and above all by a determination to destroy—at last, in agony, against one’s own deepest wishes—the great myth of the 20th century.

English-speaking readers have been told the story of Pasolini’s life many times, and often very well.

More here.

Earlier this year Gallup published some incredible statistics, showing that gen Z is our queerest generation yet, with nearly 20 percent identifying somewhere under the broad LGBTQIA+ umbrella. (Some two-thirds of this group—13 percent of gen Z—identify as bisexual; about 2 percent of zoomers identify as trans.) When I was first coming out in the early 1990s, by contrast, “1 in 10” was a common gay slogan. How did we get here, with such wide differences in identification between generations? Are there actually more queer people now, or just more out queer people? Or are those the wrong questions to ask?

Earlier this year Gallup published some incredible statistics, showing that gen Z is our queerest generation yet, with nearly 20 percent identifying somewhere under the broad LGBTQIA+ umbrella. (Some two-thirds of this group—13 percent of gen Z—identify as bisexual; about 2 percent of zoomers identify as trans.) When I was first coming out in the early 1990s, by contrast, “1 in 10” was a common gay slogan. How did we get here, with such wide differences in identification between generations? Are there actually more queer people now, or just more out queer people? Or are those the wrong questions to ask?

E

E Angus Deaton in Boston Review:

Angus Deaton in Boston Review: Elliott Ash and Stephen Hansen in VoxEU:

Elliott Ash and Stephen Hansen in VoxEU: T. J. Clark in The Nation:

T. J. Clark in The Nation: Ho-Fung Hung in Sidecar:

Ho-Fung Hung in Sidecar: Inanna is remarkably little known these days, but at the dawn of civilisation, she was vastly important. She went on to become Ishtar, who is more widely recognised, and then aspects of her character were incorporated into the goddesses Aphrodite and Venus. Of all the deities, she is arguably the one who has lived the longest.

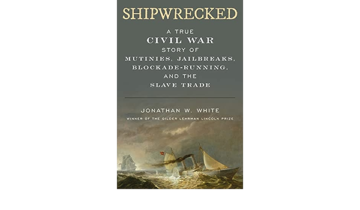

Inanna is remarkably little known these days, but at the dawn of civilisation, she was vastly important. She went on to become Ishtar, who is more widely recognised, and then aspects of her character were incorporated into the goddesses Aphrodite and Venus. Of all the deities, she is arguably the one who has lived the longest. Who was Appleton Oaksmith? One contemporary described him as a “good seaman, & a bold & daring officer.” His enemies, President Abraham Lincoln among them, judged him a scoundrel and a traitor. Oaksmith, writing six years after the Civil War, wasn’t sure what to think: “I look upon myself sometimes with a sort of doubt as to my own identity.”

Who was Appleton Oaksmith? One contemporary described him as a “good seaman, & a bold & daring officer.” His enemies, President Abraham Lincoln among them, judged him a scoundrel and a traitor. Oaksmith, writing six years after the Civil War, wasn’t sure what to think: “I look upon myself sometimes with a sort of doubt as to my own identity.” Former U.S. Vice President Al Gore has been a huge player in the fight against climate change for as long as most of us can remember. As the founder and current chair of the

Former U.S. Vice President Al Gore has been a huge player in the fight against climate change for as long as most of us can remember. As the founder and current chair of the  Like her patron goddess, Venus, Helen of Troy represents, in

Like her patron goddess, Venus, Helen of Troy represents, in  Ninety-three days

Ninety-three days This July has been the hottest in our

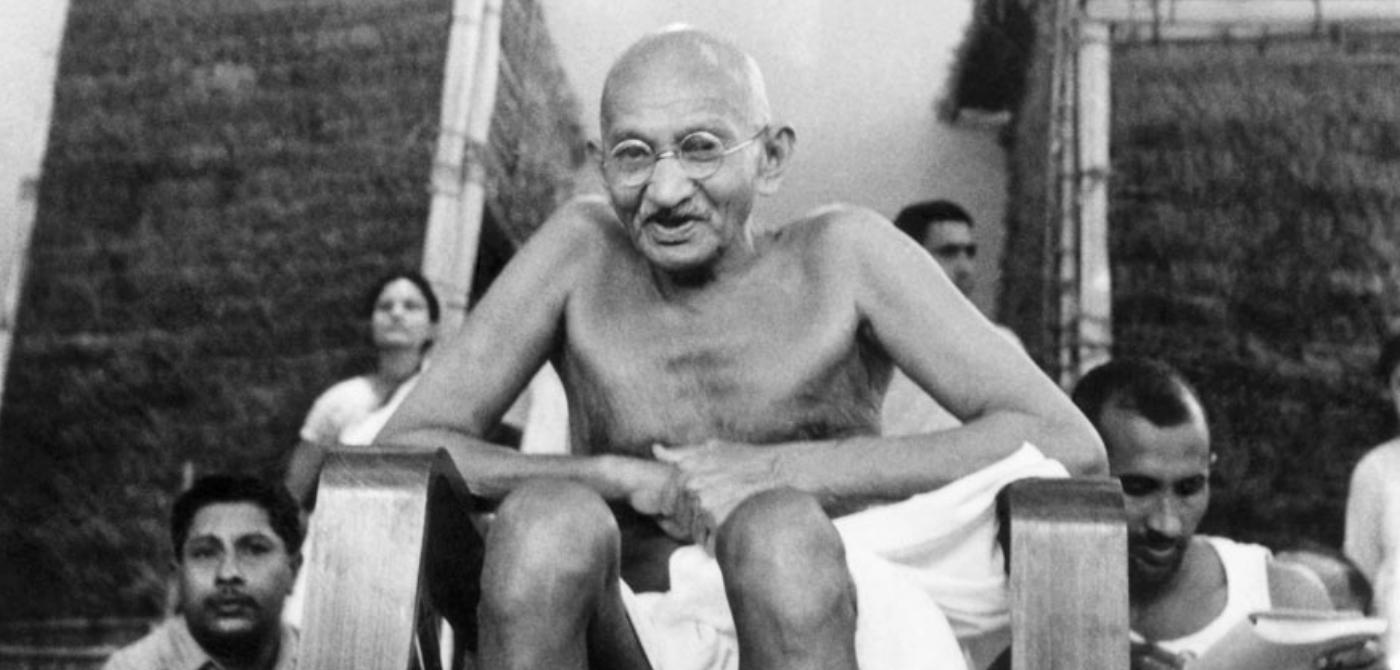

This July has been the hottest in our  I will begin on a self-conscious note. For some years, I have put off writing about Gandhi’s views on caste for my long-gestating book manuscript on Gandhi’s thought. The subject had become so fraught, as a result of recent invectives directed at Gandhi, that I did not trust myself to not get caught up in an ideological maelstrom in which anything one said by way of trying to merely even understand his views would come off as a kind of apologetics, which I had no wish to produce since, for all my admiring interest in him, I am not a Gandhi-bhakt. Indeed, as will emerge in what I am about to say, he is sometimes quite wrong on this subject as, no doubt, on others.

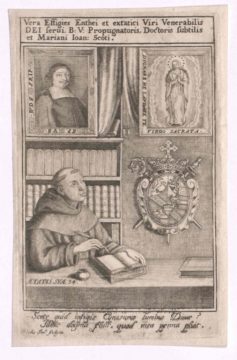

I will begin on a self-conscious note. For some years, I have put off writing about Gandhi’s views on caste for my long-gestating book manuscript on Gandhi’s thought. The subject had become so fraught, as a result of recent invectives directed at Gandhi, that I did not trust myself to not get caught up in an ideological maelstrom in which anything one said by way of trying to merely even understand his views would come off as a kind of apologetics, which I had no wish to produce since, for all my admiring interest in him, I am not a Gandhi-bhakt. Indeed, as will emerge in what I am about to say, he is sometimes quite wrong on this subject as, no doubt, on others. Scotus remains a polarising figure, but his humanist detractors would be horrified to learn that here in the

Scotus remains a polarising figure, but his humanist detractors would be horrified to learn that here in the