Paul Begala in The New York Times:

“Built for giants, inhabited by pygmies.” That’s what the legendary Texas politician Bob Eckhardt used to tell awe-struck visitors about the Texas Capitol. The Goddess of Liberty, who stands atop Austin’s dome, peers down 302 feet at the mortals below, 14 feet higher than the U.S. Capitol.

“Built for giants, inhabited by pygmies.” That’s what the legendary Texas politician Bob Eckhardt used to tell awe-struck visitors about the Texas Capitol. The Goddess of Liberty, who stands atop Austin’s dome, peers down 302 feet at the mortals below, 14 feet higher than the U.S. Capitol.

As a University of Texas law student in 1985, I was one of those pygmies. I worked for a 20-something cowboy turned newbie state representative. So, when I encountered Sonny Lamb, I felt like I’d known him for years.

Lamb is the protagonist of Lawrence Wright’s rollicking satire “Mr. Texas.” He is a soldier-rancher-failure who, by way of accidental heroism and a Machiavellian lobbyist, finds himself elected to the Texas Legislature. This is where Mr. Wright’s task becomes daunting: parodying politicians who are, in real life, parody-proof. When I worked at the Legislature, the speaker of the House was Gib Lewis, a good ol’ boy from Fort Worth who loved hunting and feared polysyllabic words. He was a veritable redneck Yogi Berra. How do you satirize a place where the speaker of the House once said, “This is unparalyzed in the state’s history,” and “I cannot tell you how grateful I am; I am filled with humidity”?

More here.

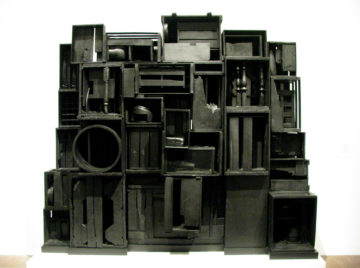

THE ICONIC LOUISE NEVELSON sculpture would appear straightforward to summarize: monochrome, modular, monumental. In general, such qualities—and to them we might add wooden, assemblage, usually black, comprising found objects—indicate an artist singularly absorbed, working through a set of formal propositions over a career, pursuing the archetypal enterprise of the modernist master. In particular, though, up close and personal, Nevelson’s sculptures are, well, defiantly weird.

THE ICONIC LOUISE NEVELSON sculpture would appear straightforward to summarize: monochrome, modular, monumental. In general, such qualities—and to them we might add wooden, assemblage, usually black, comprising found objects—indicate an artist singularly absorbed, working through a set of formal propositions over a career, pursuing the archetypal enterprise of the modernist master. In particular, though, up close and personal, Nevelson’s sculptures are, well, defiantly weird. W

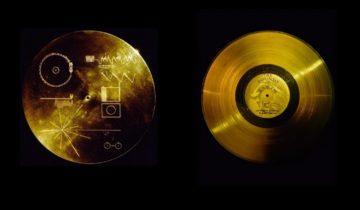

W There are alien minds among us. Not the little green men of science fiction, but the alien minds that power the facial recognition in your smartphone,

There are alien minds among us. Not the little green men of science fiction, but the alien minds that power the facial recognition in your smartphone,  T

T The ceremony takes place on the night of the full moon in February, which the Tibetans celebrate as the coldest of the year. Buddhist monks clad in light cotton shawls climb to a rocky ledge some 15,000 feet high and go to sleep, in child’s pose, foreheads pressed against cold Himalayan rocks. In the dead of the night, temperatures plummet below freezing but the monks sleep on peacefully, without shivering.

The ceremony takes place on the night of the full moon in February, which the Tibetans celebrate as the coldest of the year. Buddhist monks clad in light cotton shawls climb to a rocky ledge some 15,000 feet high and go to sleep, in child’s pose, foreheads pressed against cold Himalayan rocks. In the dead of the night, temperatures plummet below freezing but the monks sleep on peacefully, without shivering. Some

Some  I

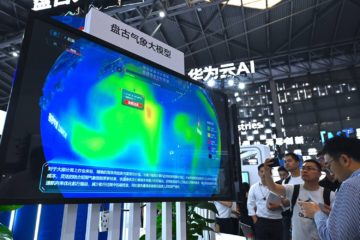

I Over the past two years, China has enacted some of the world’s earliest and most sophisticated

Over the past two years, China has enacted some of the world’s earliest and most sophisticated  There were less intimate places available, so it was odd when a woman took the seat directly facing mine across the subway aisle. I looked up from my book and right back down: a couple of months before, we’d gone home together. She had a Southern accent and a boy’s name she swore was given. Bobby. Probably spelled Bobbie or Bobbi but she didn’t say “Bobbi with an i,” which I thought cool of her. Good sex, great chemistry, and I promised but then failed to text; encountering her on the subway might have been awkward even if I weren’t reading What Were You Expecting?: A New Manual for New Parents by Drs. Laurie and Lawrence Shriver. No point hiding the cover now. Bobbi had seen it before she sat down—that much was clear when we made eye contact. She chose the seat to shame me.

There were less intimate places available, so it was odd when a woman took the seat directly facing mine across the subway aisle. I looked up from my book and right back down: a couple of months before, we’d gone home together. She had a Southern accent and a boy’s name she swore was given. Bobby. Probably spelled Bobbie or Bobbi but she didn’t say “Bobbi with an i,” which I thought cool of her. Good sex, great chemistry, and I promised but then failed to text; encountering her on the subway might have been awkward even if I weren’t reading What Were You Expecting?: A New Manual for New Parents by Drs. Laurie and Lawrence Shriver. No point hiding the cover now. Bobbi had seen it before she sat down—that much was clear when we made eye contact. She chose the seat to shame me. The protein universe just got a lot brighter.

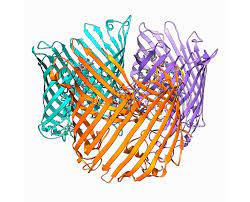

The protein universe just got a lot brighter.