William Boyd at Literary Review:

Every time this happens I’m reminded of Vladimir Nabokov’s unique and hilarious novel Pale Fire and the opening couplet of the 999-line poem that gives the book its title:

Every time this happens I’m reminded of Vladimir Nabokov’s unique and hilarious novel Pale Fire and the opening couplet of the 999-line poem that gives the book its title:

I was the shadow of the waxwing slain

By the false azure in the window pane.

I’ve reread Pale Fire several times and regularly choose it as my favourite novel when the question arises. I have read almost everything Nabokov wrote and, as with any writer one reveres, when the work has been thoroughly consumed, one becomes more and more curious about the actual person.

I happen to have one thing in common with Nabokov. Both of us appeared on the legendary French book programme Apostrophes. In fact, I appeared three times on Apostrophes, but always with other writers. Nabokov – in the enduring glow of his post-Lolita fame – had the whole show to himself.

more here.

“‘I have named the paper thus presented Calotype paper on account of its great utility in obtaining the pictures of objects with the camera obscura,’” he said, as quoted by Ellen Sharp, who notes, that “With his improved process, Talbot had reduced exposures from an hour to a few minutes, or even seconds, depending on the strength of the sun.”

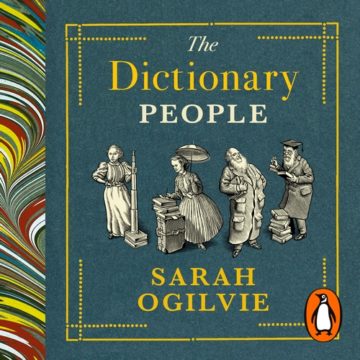

“‘I have named the paper thus presented Calotype paper on account of its great utility in obtaining the pictures of objects with the camera obscura,’” he said, as quoted by Ellen Sharp, who notes, that “With his improved process, Talbot had reduced exposures from an hour to a few minutes, or even seconds, depending on the strength of the sun.” When James Murray, the then editor of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), received the first bundle of quotations from a “Dr William Chester Minor” of Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum in 1883, he presumed the man worked there. In the first volume of the dictionary, published five years later, Minor is thanked as “Dr WC Minor, Crowthorne, Berks”. It was only in 1890 that Murray discovered the truth: that while Minor was an American surgeon, he was also a paranoid schizophrenic and probable sex addict who had been committed to Broadmoor after shooting a man dead.

When James Murray, the then editor of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), received the first bundle of quotations from a “Dr William Chester Minor” of Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum in 1883, he presumed the man worked there. In the first volume of the dictionary, published five years later, Minor is thanked as “Dr WC Minor, Crowthorne, Berks”. It was only in 1890 that Murray discovered the truth: that while Minor was an American surgeon, he was also a paranoid schizophrenic and probable sex addict who had been committed to Broadmoor after shooting a man dead. CLAUDINE GAY

CLAUDINE GAY I

I A number of things have changed regarding climate change over the last 13 years. On the negative side, annual emissions continued to increase slowly or maybe

A number of things have changed regarding climate change over the last 13 years. On the negative side, annual emissions continued to increase slowly or maybe  The study of cognition and sentience would be greatly abetted by the discovery of intelligent alien beings, who presumably developed independently of life here on Earth. But we do have more than one data point to consider: certain vertebrates (including humans) are quite intelligent, but so are certain cephalopods (including octopuses), even though the last common ancestor of the two groups was a simple organism hundreds of millions of years ago that didn’t have much of a nervous system at all. Peter Godfrey-Smith has put a great amount of effort into trying to figure out what we can learn about the nature of thinking by studying how it is done in these animals with very different brains and nervous systems.

The study of cognition and sentience would be greatly abetted by the discovery of intelligent alien beings, who presumably developed independently of life here on Earth. But we do have more than one data point to consider: certain vertebrates (including humans) are quite intelligent, but so are certain cephalopods (including octopuses), even though the last common ancestor of the two groups was a simple organism hundreds of millions of years ago that didn’t have much of a nervous system at all. Peter Godfrey-Smith has put a great amount of effort into trying to figure out what we can learn about the nature of thinking by studying how it is done in these animals with very different brains and nervous systems. In 1958, the young Indian poet Purushottama (P.) Lal was living in Calcutta, writing in English, and looking for a publisher. Unable to find one, he gathered a small group of college friends who were also convinced that English was a legitimate Indian language for creative writing, including Anita Desai, and started an independent press, known still as Writers Workshop. During what became their legendary Sunday morning

In 1958, the young Indian poet Purushottama (P.) Lal was living in Calcutta, writing in English, and looking for a publisher. Unable to find one, he gathered a small group of college friends who were also convinced that English was a legitimate Indian language for creative writing, including Anita Desai, and started an independent press, known still as Writers Workshop. During what became their legendary Sunday morning  Of all the forms of human intellect that one might expect

Of all the forms of human intellect that one might expect  As Warhol was patron saint of the New York night, Ed Ruscha is the quintessential artist of Los Angeles and its heartbreaking light. His paintings, books, photographs, films, and works on paper — made with ingredients as disparate as gunpowder, sulfuric acid, chocolate, urine, Pepto-Bismol, tobacco, and rose petals — could only come from someone who embodies L.A.’s glamour and chaos, its self-consciousness and banal hopes. Peter Plagens once

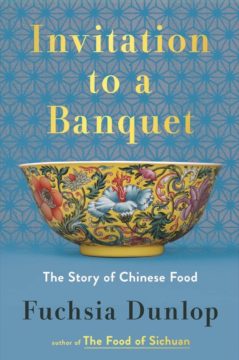

As Warhol was patron saint of the New York night, Ed Ruscha is the quintessential artist of Los Angeles and its heartbreaking light. His paintings, books, photographs, films, and works on paper — made with ingredients as disparate as gunpowder, sulfuric acid, chocolate, urine, Pepto-Bismol, tobacco, and rose petals — could only come from someone who embodies L.A.’s glamour and chaos, its self-consciousness and banal hopes. Peter Plagens once  Collectively, the book’s chapters present Chinese cuisine as diverse and dynamic. Dunlop describes how, in the ninth century, the majority of the Chinese population switched from millet to rice, their present staple, after losing the millet-growing north of the country to nomads. She also explains the impact of the chilli pepper. Brought from the Americas in the late 16th century, it imparted a fiery character to the cooking of Sichuan and Hunan, further distinguishing these regional cuisines from the milder fare of coastal cities like Canton. We also hear about borscht, a legacy of the Russians who settled in Shanghai after the Bolshevik Revolution. Shanghainese cooks subsequently put their own spin on the dish, now known as luosongtang, replacing the beetroot with tomatoes to make a dense soup comprising ‘squares of cabbage, slices of carrot and potato and a few tiny fragments of beef’.

Collectively, the book’s chapters present Chinese cuisine as diverse and dynamic. Dunlop describes how, in the ninth century, the majority of the Chinese population switched from millet to rice, their present staple, after losing the millet-growing north of the country to nomads. She also explains the impact of the chilli pepper. Brought from the Americas in the late 16th century, it imparted a fiery character to the cooking of Sichuan and Hunan, further distinguishing these regional cuisines from the milder fare of coastal cities like Canton. We also hear about borscht, a legacy of the Russians who settled in Shanghai after the Bolshevik Revolution. Shanghainese cooks subsequently put their own spin on the dish, now known as luosongtang, replacing the beetroot with tomatoes to make a dense soup comprising ‘squares of cabbage, slices of carrot and potato and a few tiny fragments of beef’. Jacob Keanik scanned his binoculars over the field of ice surrounding our sailboat. He was looking for the polar bear that had been stalking us for the past 24 hours, but all he could see was an undulating carpet of blue-green pack ice that stretched to the horizon. “Winter is coming,” he murmured. Jacob had never seen Game of Thrones and was unaware of the phrase’s reference to the show’s menacing hordes of ice zombies, but to us, the threat posed by this frozen horde was equally dire. Here in remote Pasley Bay, deep in the Canadian Arctic, winter would bring a relentless tide of boat-crushing ice. If we didn’t find a way out soon, it could trap us and destroy our vessel—and perhaps us too.

Jacob Keanik scanned his binoculars over the field of ice surrounding our sailboat. He was looking for the polar bear that had been stalking us for the past 24 hours, but all he could see was an undulating carpet of blue-green pack ice that stretched to the horizon. “Winter is coming,” he murmured. Jacob had never seen Game of Thrones and was unaware of the phrase’s reference to the show’s menacing hordes of ice zombies, but to us, the threat posed by this frozen horde was equally dire. Here in remote Pasley Bay, deep in the Canadian Arctic, winter would bring a relentless tide of boat-crushing ice. If we didn’t find a way out soon, it could trap us and destroy our vessel—and perhaps us too. In 1848, when Louis Pasteur was a young chemist still years away from discovering how to sterilize milk, he discovered something peculiar about crystals that accidentally formed when an industrial chemist boiled wine for too long. Half of the crystals were recognizably tartaric acid, an industrially useful salt that grew naturally on the walls of wine barrels. The other crystals had exactly the same shape and symmetry, but one face was oriented in the opposite direction.

In 1848, when Louis Pasteur was a young chemist still years away from discovering how to sterilize milk, he discovered something peculiar about crystals that accidentally formed when an industrial chemist boiled wine for too long. Half of the crystals were recognizably tartaric acid, an industrially useful salt that grew naturally on the walls of wine barrels. The other crystals had exactly the same shape and symmetry, but one face was oriented in the opposite direction.

Karen Hopkin: This is Scientific American’s 60-Second Science. I’m Karen Hopkin. They say that practice makes perfect.

Karen Hopkin: This is Scientific American’s 60-Second Science. I’m Karen Hopkin. They say that practice makes perfect.