by Claire Chambers

I have already written columns for 3 Quarks Daily about starting Hindi language-learning early in the Covid-19 pandemic, continuing to intermediate level as things opened up, and then learning Urdu alongside Hindi once Covid became less of a problem.

However, as is suggested by the post-2020 timestamp of my linguistic odyssey, I am internet ki bachi, a child of the internet. At least at the beginning, I was confined to my house using apps and working with online language tutors during successive lockdowns. As a consequence, I started to become passable in reading, listening, speaking, and writing on my keyboard with the help of a plug-in – but I could not write by hand.

In the final instalment of my previous trilogy, the blog post concerning Urdu, I discussed my hesitancy about handwriting. Finding myself reasonably proficient in constructing emails and short documents on the computer, learning Urdu calligraphy seemed unnecessarily burdensome on my mental capacity. There’s no familial need for me to produce handwritten notes, so I thought this competence wasn’t worth cultivating.

However, Leanne Ogasawara in particular encouraged me to think again.  Leanne argued that the craftmanship of handwriting establishes a deeper and more personal link with the target language. Relatedly, it also has links to memorization: perhaps it’s something to do with muscle memory. I revised for all my A-Level exams by writing notes by hand and, ever since, if I really want to remember something, forming the words with a pen gives me the best chance of doing so. Anyway, Leanne spoke passionately about how writing in Japanese unlocked new insights for her, and shared her experience of reading Jing Tsu’s book, Kingdom of Characters: The Language Revolution that Made China Modern about the Chinese written word. My own reading of this book gave me this wonderful description of surrendering to another tongue:

Leanne argued that the craftmanship of handwriting establishes a deeper and more personal link with the target language. Relatedly, it also has links to memorization: perhaps it’s something to do with muscle memory. I revised for all my A-Level exams by writing notes by hand and, ever since, if I really want to remember something, forming the words with a pen gives me the best chance of doing so. Anyway, Leanne spoke passionately about how writing in Japanese unlocked new insights for her, and shared her experience of reading Jing Tsu’s book, Kingdom of Characters: The Language Revolution that Made China Modern about the Chinese written word. My own reading of this book gave me this wonderful description of surrendering to another tongue:

I had to leave Chinese behind in order to immerse myself in English and know it from the inside. I never had to think so hard in dogmatic ways in Chinese to arrive at sense-making. The two language worlds did not accord; they clashed. Chinese had a prior claim to every experience that was expressive, intuitive, and creative to me, while English felt like a corrective device that straightened and twisted me to fit a new mold. It was not enough to just master writing, reading comprehension, and vocabulary. To think in English, I had to breathe and live a worldview that was expressed and constructed in that language.

This is resonant of how one has to temporarily jettison old ways of thinking to learn a language. True, Hindi–Urdu have more in common with English than Chinese does. Even so, if there are losses in relinquishing familiarity and fluency in one’s native tongue, the gain of understanding and internalizing the target language ‘from the inside’ in linguistic and cultural assimilation can be immeasurable.

This is resonant of how one has to temporarily jettison old ways of thinking to learn a language. True, Hindi–Urdu have more in common with English than Chinese does. Even so, if there are losses in relinquishing familiarity and fluency in one’s native tongue, the gain of understanding and internalizing the target language ‘from the inside’ in linguistic and cultural assimilation can be immeasurable.

Despite Leanne’s wise counsel, I was at first resolute about my lazy stance that in the year of our Lord 2023 there was no pressing need for the level-up of forming letters with a pen. It was towards the middle of last year, though, that I began to waver. For one thing, if I want to sit for exams like GCSE or A level (and I do), then it slowly dawned on me that writing by hand would be necessary.

I’d assumed because I knew the Devanagari and Nastaliq scripts quite intimately by this point, it should have been easy enough to form the letters if I only tried. Not so! The few early and unsupervised attempts I made to write simple words with pen and paper in Hindi or Urdu ended in shame-faced failure. I realized that my reading was very passive. When I tried proactively to construct the letters from memory, my mind would draw a blank about what most, if not all, of them looked like. As with many academics, I’ve always been more of a reading learner than a visual or kinesthetic one.

That was when the plan to do a language-learning homestay in South Asia first began to formulate in my mind. I initially thought of staying with an Urdu-speaking family in the city of Lucknow in India’s northern Uttar Pradesh province. The metropolis was certainly the right choice for me because of its storied history, cultural syncretism, and the high reputation its denizens have for their courtly language use. But in the end, personal contacts meant I resided with a friend’s Lucknow-based parents, who happen to be Hindi speakers.

That was when the plan to do a language-learning homestay in South Asia first began to formulate in my mind. I initially thought of staying with an Urdu-speaking family in the city of Lucknow in India’s northern Uttar Pradesh province. The metropolis was certainly the right choice for me because of its storied history, cultural syncretism, and the high reputation its denizens have for their courtly language use. But in the end, personal contacts meant I resided with a friend’s Lucknow-based parents, who happen to be Hindi speakers.

This was actually great, since in my view Devanagari is harder to write in than Nastaliq. That’s because, as I’ve argued before, Urdu features a reduced number of letters compared to Hindi, with many being variations of the same letterforms. For instance, Urdu deploys variations like خ ح چ ج and ب ت ث پ, among other letter groups. It’s all about whether the nuqte or diacritics are above or below the line, which is admittedly confusing enough. But Devanagari includes no such patterns, so it was good to be learning from native speakers of Hindi.

I know my subjective position that Urdu writing is easier than Hindi might strike some readers as odd. I should say that I find reading Hindi a more straightforward task than right-to-left Urdu. But with writing in Devanagari, there is so much to think about, not least anticipating the short ि (choti e) matra which comes before the letter whereas one pronounces it afterwards. I know most Urdu letters have four forms (isolated, initial, medial, and final) and that it can be hard to judge the slant each time, or where to place letters: above or below the line. I just go for a sort of squared-off naskh along the line, rather than aiming for a hanging or suspended script. Having said that, I’m not claimng my writing is legible. Indeed, one of my teachers says I’m very bad at forming shoshe, the little downward strokes on which diacritical marks are supposed to sit. But maybe because I only had a week of amnay-samnay, ruu-ba-ruu, or face-to-face Hindi handwriting compared to the month of Urdu I’ll talk about shortly, I am going to stand by my controversial opinion.

My time in Lucknow was also a great stay because the couple I lived with for a week were so kind to me. I had known the three of us would speak together in Hindi a lot, as I had been told that this couple were (wrongly, in my view) unconfident in their English. But what was even better was that the mother steered me towards writing Devanagari by hand. This woman, Anjali, had been a nursery school teacher when her own daughter (my young friend) was small. She accordingly had oceans of patience to pour on the childlike although middle-aged writer in front of her. Learning languages starting from the beginning is infantilizing. Somehow struggling awkwardly to form the letters with a pen is a necessary part of this artless experience: you would be denying yourself something not to have it.

Anjali would sit with me for a few hours each day going through the Hindi वर्णमाला (varnamala or alphabet). The ‘वर्ण’ (varna) part of the word refers to letters or characters in a script. It represents individual phonetic units or symbols used in writing. More evocatively, the ‘माला’ (mala) part means a string or garland. In this context, it symbolizes a series or sequence of items threaded together in a specific order. As such, वर्णमाला (varnamala) can be understood as a ‘necklace of characters’, representing the organized sequence of letters in an alphabet or script. Arre wah, beautiful!

Anjali would sit with me for a few hours each day going through the Hindi वर्णमाला (varnamala or alphabet). The ‘वर्ण’ (varna) part of the word refers to letters or characters in a script. It represents individual phonetic units or symbols used in writing. More evocatively, the ‘माला’ (mala) part means a string or garland. In this context, it symbolizes a series or sequence of items threaded together in a specific order. As such, वर्णमाला (varnamala) can be understood as a ‘necklace of characters’, representing the organized sequence of letters in an alphabet or script. Arre wah, beautiful!

Anjali certainly led me to festoon myself with these letters, teaching me their pronunciation (though my accent is incorrigibly terrible), their ordering sequence, and the logic behind them. Coming home from work each day, her husband, who is only a few years older than me, would smile with avuncular pride at my progress. Over the week, he started to bring me children’s books about the letters and matras to help push me on. These included those handwriting workbooks where you can trace over dotted lettering to practice, which are superb for building muscle memory in the early stages.

Inspired by this trip, a few months later I went searching for a local Urdu teacher in my hometown of Leeds in northern England. Handwriting is so hard to learn online; it’s the one tactile skill that doesn’t really translate for a digital world, try though I have. I remember some frustrating sessions when I would take pictures of my writing and send them by WhatsApp to a teacher in Pakistan before waiting for his feedback. This was time-consuming and inadequate, despite his expertise as an instructor, so I knew that having someone close by would be much more satisfactory. I found a young woman who had moved to Britain from West Punjab a few years earlier to get married. Now we meet every week at her house to concentrate on getting my writing up to scratch for the Edexcel GCSE in Urdu I have decided to take this summer. (I’m not convinced I will pass, though. Yesterday I was writing mere foundation level essays in Urdu and finding it really hard. The papers are set up in such a way that I get asked what my school is like (!) and how I celebrated last Eid. My teacher here in Karachi said, ‘Just tell them you’re going to write about Christmas’, so that is what I did for this practice session! Meanwhile, the school essay was pure fiction.)

One ingenious idea I came up with was to use the glorious Rekhta website, with its treasure trove of stories and poems, to flip between Hindi and Urdu. In order to practise Hindi writing, I could select the Nastaliq setting at the top of the page and try to transcribe the Urdu words into Devanagari. And vice versa for Urdu, of course. I consider this a useful tip for those wanting to learn the two languages at the same time. It obviates the need for a teacher, since at the click of a button you can move into the other language and mark your own work.

One ingenious idea I came up with was to use the glorious Rekhta website, with its treasure trove of stories and poems, to flip between Hindi and Urdu. In order to practise Hindi writing, I could select the Nastaliq setting at the top of the page and try to transcribe the Urdu words into Devanagari. And vice versa for Urdu, of course. I consider this a useful tip for those wanting to learn the two languages at the same time. It obviates the need for a teacher, since at the click of a button you can move into the other language and mark your own work.

Friends had affirmed that writing leads to a more hands-on approach to the second language, and now I could see they were right. I discovered that this process not only enhanced my understanding of these sister languages but also fuelled my fascination to such an extent that my subconscious mind began to spin fantasies of crafting the elusive characters. I became deeply engrossed in the process, to the point where I would regularly dream about forming the letters. My fixation on mastering the scripts revealed a stark contrast between my proficiency in English spelling and my challenges with the unfamiliar letters of Hindi and Urdu. Whereas I’m usually a stickler for spelling in English, I’m hopeless at remembering which letters form particular words in both Hindi and Urdu. In Urdu, knowing when کھ or خ (kh), ت or ط (t), and س ,ص, or ث (s) was required were particular roadblocks. In Hindi, it was which sh (श or ष) and the matras signalling vowels between letters that I found especially hard to gauge.

Next I plotted a longer South Asian sojourn. After encountering visa complications for my intended trip to both Pakistan and India, I found myself joyfully ‘stuck’ for a whole month in Karachi with a British friend employed by the UN. Because of her monolingualism, my immersion experience wasn’t as consistent as a homestay. That said, I got to speak a lot more Urdu than usual with her household staff, as well as workers in the surrounding service industry. To enrich my language capabilities further, I enlisted the tutorship of a fantastic Urdu teacher, Idrees Kasbati from SUN Tutors Academy, who visited every day except at the weekend for two-hour sessions at our house. Despite the apparent setback of not making it to India, the unexpected turn of staying rooted in the single city of Karachi has proven to be very beneficial for both my language-learning journey and overall wellbeing.

Next I plotted a longer South Asian sojourn. After encountering visa complications for my intended trip to both Pakistan and India, I found myself joyfully ‘stuck’ for a whole month in Karachi with a British friend employed by the UN. Because of her monolingualism, my immersion experience wasn’t as consistent as a homestay. That said, I got to speak a lot more Urdu than usual with her household staff, as well as workers in the surrounding service industry. To enrich my language capabilities further, I enlisted the tutorship of a fantastic Urdu teacher, Idrees Kasbati from SUN Tutors Academy, who visited every day except at the weekend for two-hour sessions at our house. Despite the apparent setback of not making it to India, the unexpected turn of staying rooted in the single city of Karachi has proven to be very beneficial for both my language-learning journey and overall wellbeing.

It was an educational opportunity conversing in Urdu with the housekeeper and his family while my English-speaking friend was away on one of her many work trips. The five-year-old girl of the family provided engaging stream-of-consciousness soliloquies, touching on topics ranging from pets and cousins to a wedding in the village and her school life. One memorable moment arose when she expressed her feelings about my friend’s cats, remarking, ‘Noodle Pickle se ghussa hai kyunke “Main orange hoon aur tum bhi orange ho”’ (Noodle is upset with Pickle because ‘I am orange and so are you’). Trust a primary school pupil to understand the sibling rivalry of two ginger toms! Fortunately, my role mainly involved nodding and offering affirmative phrases like ‘Haan’, ‘Accha?’, and ‘Ye sahi baat hai’, sparing me the need to fully comprehend the idiomatic chatter of this whip-smart young girl. Working with infants is thought to be a uniquely facilitative training, because young children just witter at you, unbothered whether you understand them or not.

Returning to Pakistan for the first time since the pandemic, this time armed with language, felt like getting glasses with a sharper prescription or activating noise-cancellation on headphones. Every detail became clearer and my confidence increased. Things not only came into sharper focus for me in South Asia but also in encounters within the British diaspora after learning Hindi-Urdu. I think people who never learn the language miss so many details. I’m motivated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s stirring summons: ‘if you are interested in talking about the other, and/or in making a claim to be the other, it is crucial to learn other languages’.

Returning to Pakistan for the first time since the pandemic, this time armed with language, felt like getting glasses with a sharper prescription or activating noise-cancellation on headphones. Every detail became clearer and my confidence increased. Things not only came into sharper focus for me in South Asia but also in encounters within the British diaspora after learning Hindi-Urdu. I think people who never learn the language miss so many details. I’m motivated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s stirring summons: ‘if you are interested in talking about the other, and/or in making a claim to be the other, it is crucial to learn other languages’.

This new vision held true right from finding my way out of Jinnah International Airport via an exit sign emblazoned with ‘Bahar jane ke rasta’ (literally ‘The way for going outside’) to navigating the Nastaliq signage-sprouting streets. My phone’s camera captured moments, from snapshots of the Beach Luxury Hotel’s toilet (Bare meherbani wash basin mein paaon nahin dhonen – Please do not wash your feet in the wash basin) to the sign spied in a tailor’s shop (Machinon ki service ka kaam tasali bakhsh kiya jata hai. Chiffon, cotton, jersey, malai lawn ki home service ki jati hai – Machine servicing done to your satisfaction. Home service for chiffon, cotton, jersey, malai lawn). Each sign is a yardstick attesting to how far my comprehension has travelled.

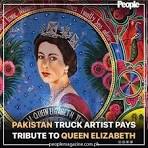

Amid the chaotic contradictions of the streets, a Queen Elizabeth II memorial mural, created when she died in 2022 and painted in vibrant truck art style, caught my eye under a dusty overpass – an incongruous homage blending cultures. Alongside, Palestine and Kashmir solidarity posters spoke of the enormity of global issues. As we sped past, I glimpsed political posters, some adorned with an elaborate Arabicized Urdu font, representing diverse ideologies – MQM, PPP, and those of various religious parties – each a testament to the complex alphabet soup of Pakistani politics. I indulged in local culture, purchasing sweatshirts featuring Urdu calligraphy and changing my phone’s language setting from Hindi to Urdu for a more complete linguistic submersion. Soon stumped by the buttons being on the ‘wrong’ side, and chastened by having accidentally turned my WhatsApp profile picture into a random photo from my phone’s camera roll, before too long I turned back to left-to-right Devanagari to avoid further mishaps.

Yet, amidst the hustle and bustle, bheed-bhaad, or amad-o-raft, the act of reading felt more private and seductive than ever. I forged new connections to the written word, from studying for GCSE to pondering the finer details of Urdu. I experienced a tongue-tied reticence in my worry over using Hindi words like pati for husband or shauhar, parivar for family or khandaan, and sundar for beautiful or khubsurat. But the soft power of Bollywood means that these words are easily understood, even if I sometimes sound like a BJP-wali. More than that, I was relieved to find my timidity mirrored by a shop vendor I met, who was embarrassed over what he called his ‘tooti phuti’ (broken) English. Literally this means broken, and figuratively it is ‘messed up’, but at the time I confused it for the ‘tutti frutti’ ice cream flavour!

Yet, amidst the hustle and bustle, bheed-bhaad, or amad-o-raft, the act of reading felt more private and seductive than ever. I forged new connections to the written word, from studying for GCSE to pondering the finer details of Urdu. I experienced a tongue-tied reticence in my worry over using Hindi words like pati for husband or shauhar, parivar for family or khandaan, and sundar for beautiful or khubsurat. But the soft power of Bollywood means that these words are easily understood, even if I sometimes sound like a BJP-wali. More than that, I was relieved to find my timidity mirrored by a shop vendor I met, who was embarrassed over what he called his ‘tooti phuti’ (broken) English. Literally this means broken, and figuratively it is ‘messed up’, but at the time I confused it for the ‘tutti frutti’ ice cream flavour!

I witnessed jugaad or life-hack innovations, such as a man walking his dog from a motorcycle or a shower tray repurposed as a storm drain cover, which highlighted the resilience and creativity engrained in everyday life here. Perhaps the best example, though, is Murree Sapphire Gin. The Murree Brewery, which operates on the edges of Pakistan’s strict law around alcohol prohibition for Muslims, wanted to make a gin that looked like Bombay Sapphire. Finding the iconic blue glass too expensive to manufacture, they simply coloured the gin itself a striking azure hue!

I witnessed jugaad or life-hack innovations, such as a man walking his dog from a motorcycle or a shower tray repurposed as a storm drain cover, which highlighted the resilience and creativity engrained in everyday life here. Perhaps the best example, though, is Murree Sapphire Gin. The Murree Brewery, which operates on the edges of Pakistan’s strict law around alcohol prohibition for Muslims, wanted to make a gin that looked like Bombay Sapphire. Finding the iconic blue glass too expensive to manufacture, they simply coloured the gin itself a striking azure hue!

I saw two professional-looking female cyclists in lycra pedalling furiously along a fume-choked dual carriageway, while some impoverished people slept on concrete in the dusty road’s central reservation. A whimsical sight was a goat wandering down the same traffic separator clad in a man’s Fair Isle cardigan to keep the animal warm in Karachi’s winter. These are a few of the idiosyncracies that make Pakistan unforgettable.

Just as the becardiganned goat points to the eccentric yet resilient spirit of this country, my stay has beckoned me towards the strange but enduring mystery of language. An oceanic submersion is gained by surrendering to its depths. Handwriting, I now appreciate, is jugaad that helps with language acquisition. At the same time, it’s more than a life hack. Writing by hand is something that cannot easily be hacked. It is a sophisticated language practice which is hard to reproduce by algorithms or artificial intelligence. It makes demands on us of discipline, ingenuity, artistry, and – above all – humanity. Pakistan and India, homes of the languages of my heart, have so much to teach the world about all of these things.