Blake Smith in American Affairs:

Blake Smith in American Affairs:

Raymond Geuss, Cambridge philosopher, is a prominent critic of liberalism and neoliberalism, and of the tradition of anglophone analytic political philosophy that he sees as their ideological prop. His scholarship, since the 1970s, can be read as an attempt to model another form of thinking, an approach inspired by classical antiquity, Nietzsche, and the Frankfurt school. Against what he sees as the pallid abstractions of Anglo-American political philosophy, Geuss presents himself as a champion of a more skeptical, historically informed way of thinking about politics. In his new book, Not Thinking Like a Liberal, Geuss gives an account of the autobiographical origins of this mode of thought and, more ambitiously, though also more vaguely, gestures toward an alternative to liberalism.1

Not Thinking Like a Liberal traces Geuss’s education, first at an unusual Catholic boarding school in the 1950s, and then at Columbia University with figures such as Sidney Morgenbesser. As a memoir, the book is not particularly compelling. It contains little in the way of events, psychology, or gossip. Geuss underplays, for example, the conflict with Morgenbesser that eventually led to their break and, in a notable silence, avoids discussion of Robert Nozick, who was also Morgenbesser’s student (as an undergraduate) during that era. Nozick became one of the most prominent philosophers in the tradition Geuss despises and is a frequent target of his polemic in other writings.

Not Thinking is rather a paean to Geuss’s influences. This mode of exposition allows him to express his political and philosophical commitments without having to argue for them, presenting them instead as aspects of his character acquired through engagement with his teachers. Geuss sees it as his good fortune that these influences equipped him to avoid the almost irresistibly stultifying influence of liberalism on Americans’ minds. He was able to escape this stupefaction, he writes, thanks to the peculiar combination of Catholic and Marxist influences among the refugee clergymen who staffed his school.

More here.

HAVE YOU NOTICED lately that everything is shit? Things were very shitty the year before last, they became even shittier last year, and now everything is just indescribably shit. As a species, we’ve been stuck with this aspect of the human condition for around 300,000 years. But the question of how to respond to it intellectually and emotionally arises with fresh urgency in each new generation. And in the face of each fresh piece of shit. Traditionally, one role of philosophy has been to aid us in this task. Friar Lawrence advises Romeo, banished from his city and the arms of his girl, to sip “Adversity’s sweet milke, Philosophie.” However, over the past couple of centuries, with the transformation of philosophy into an academic discipline, its connection with self-help has largely been severed. The aim of Kieran Setiya’s new book Life Is Hard is to recapture philosophy’s ancient mission of “helping us find our way” in the face of life’s afflictions.

HAVE YOU NOTICED lately that everything is shit? Things were very shitty the year before last, they became even shittier last year, and now everything is just indescribably shit. As a species, we’ve been stuck with this aspect of the human condition for around 300,000 years. But the question of how to respond to it intellectually and emotionally arises with fresh urgency in each new generation. And in the face of each fresh piece of shit. Traditionally, one role of philosophy has been to aid us in this task. Friar Lawrence advises Romeo, banished from his city and the arms of his girl, to sip “Adversity’s sweet milke, Philosophie.” However, over the past couple of centuries, with the transformation of philosophy into an academic discipline, its connection with self-help has largely been severed. The aim of Kieran Setiya’s new book Life Is Hard is to recapture philosophy’s ancient mission of “helping us find our way” in the face of life’s afflictions. The girls and women of Iran are just bitchin’ brave, flipping the bird at its Supreme Leader in a challenge to one of the most significant revolutions in modern history. Day after dangerous day, on open streets and in gated schools, in a flood of tweets and brazen videos, they have ridiculed a theocracy that deems itself the government of God. The average age of the protesters who have been arrested is just fifteen, the Revolutionary Guard’s deputy commander

The girls and women of Iran are just bitchin’ brave, flipping the bird at its Supreme Leader in a challenge to one of the most significant revolutions in modern history. Day after dangerous day, on open streets and in gated schools, in a flood of tweets and brazen videos, they have ridiculed a theocracy that deems itself the government of God. The average age of the protesters who have been arrested is just fifteen, the Revolutionary Guard’s deputy commander  Fredric Jameson in Sidecar:

Fredric Jameson in Sidecar: Alden Young in Phenomenal World:

Alden Young in Phenomenal World: Blake Smith in American Affairs:

Blake Smith in American Affairs: I

I One of the funny things about adolescence is that the world can seem enormous, brimming with possibility, while at the same time the urgency to define oneself — fastidiously curating likes and dislikes, ruthlessly sorting people according to their musical tastes — can make the world feel extremely small.

One of the funny things about adolescence is that the world can seem enormous, brimming with possibility, while at the same time the urgency to define oneself — fastidiously curating likes and dislikes, ruthlessly sorting people according to their musical tastes — can make the world feel extremely small.

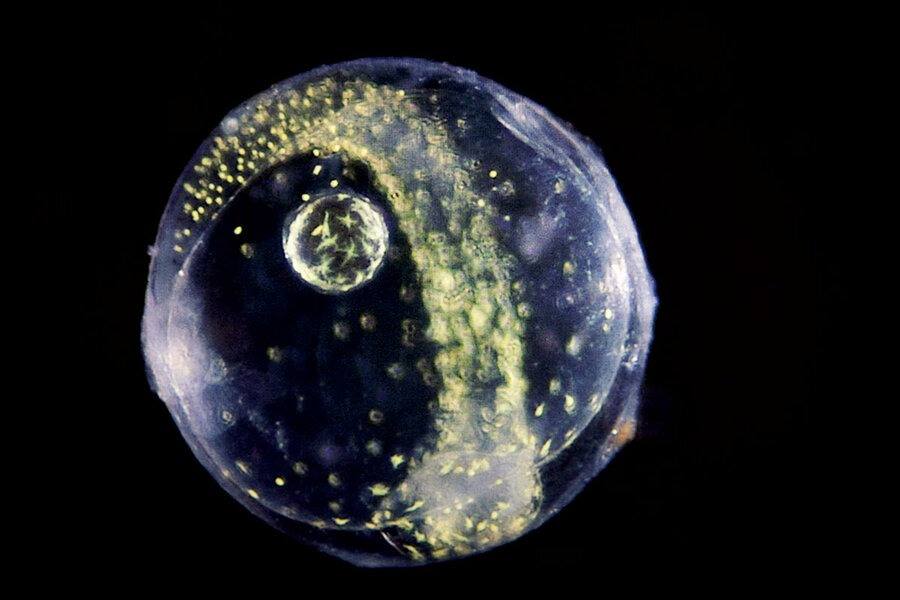

Three chemists who pioneered a useful technique called click chemistry to join molecules together efficiently have won this year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Three chemists who pioneered a useful technique called click chemistry to join molecules together efficiently have won this year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Love hungers for knowledge. For someone newly in love, nothing is better than learning about the beloved, nothing better than revealing yourself to them in turn. “The talk of lovers who have just declared their love,” writes Iris Murdoch in The Bell (1958), “is one of life’s most sweet delights. . . . Each one in haste to declare all that he is, so that no part of his being escapes the hallowing touch.”

Love hungers for knowledge. For someone newly in love, nothing is better than learning about the beloved, nothing better than revealing yourself to them in turn. “The talk of lovers who have just declared their love,” writes Iris Murdoch in The Bell (1958), “is one of life’s most sweet delights. . . . Each one in haste to declare all that he is, so that no part of his being escapes the hallowing touch.” “I have always wanted to write the sort of book that I find it impossible to talk about afterward, the sort of book that makes it impossible for me to withstand the gaze of others,” writes Annie Ernaux’s narrator near the end of her 1998 autofiction, Shame. Ernaux takes the sentiment further in the opening lines of her 2008 book, The Possession: “I have always wanted to write as if I would be gone when the book was published. To write as if I were about to die—no more judges.”

“I have always wanted to write the sort of book that I find it impossible to talk about afterward, the sort of book that makes it impossible for me to withstand the gaze of others,” writes Annie Ernaux’s narrator near the end of her 1998 autofiction, Shame. Ernaux takes the sentiment further in the opening lines of her 2008 book, The Possession: “I have always wanted to write as if I would be gone when the book was published. To write as if I were about to die—no more judges.” The Swiss composer Othmar Schoeck, who lived from 1886 to 1957, is little known outside his native land, but his moments of fame have been as striking as they are strange. For one thing, Schoeck gained the admiration of several leading writers of the twentieth century. Hermann Hesse ranked Schoeck’s songs alongside those of Schubert and Schumann; James Joyce considered him a rival to Stravinsky; Thomas Mann also thought highly of him. A further quiver of notoriety followed in the nineteen-seventies, when, as Calvin Trillin

The Swiss composer Othmar Schoeck, who lived from 1886 to 1957, is little known outside his native land, but his moments of fame have been as striking as they are strange. For one thing, Schoeck gained the admiration of several leading writers of the twentieth century. Hermann Hesse ranked Schoeck’s songs alongside those of Schubert and Schumann; James Joyce considered him a rival to Stravinsky; Thomas Mann also thought highly of him. A further quiver of notoriety followed in the nineteen-seventies, when, as Calvin Trillin