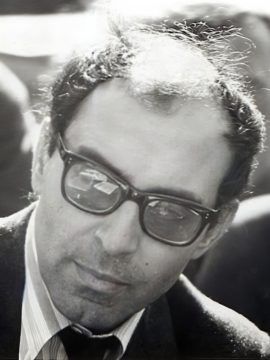

Fredric Jameson in Sidecar:

Fredric Jameson in Sidecar:

After decades in which inscrutable titles signed Godard popped up as regularly as clockwork in the film festivals, while the image of their maker deteriorated from rebel into dirty old man, if not technologically obsessed sage, it is stunning, leafing through the filmographies, to remember how much these films counted as events for us as we waited for each new and unexpected one in the 1960s, how intensely we scrutinized the political engagements of the Dziga Vertov group, with what genuinely engaged curiosity we asked ourselves what the end of the political period would bring, and later on what we were to do with the final works of the ‘humanist’ period, where they came from, and whether they meant a falling off or a genuine renewal.

Throughout all this we were entertained or provoked by the increasingly ignoble ‘thoughts’ or paradoxes which either demanded meditation or inspired a mild contempt, tempered by the constant reminder that visuality, if it thinks, does so in a way not necessarily accessible to the rest of us; while his films went on ‘thinking’ in chiasmatic images: Belmondo imitating Bogart, Piccoli inviting Bardot to use his bathwater (‘I’m not dirty’), the world conquerors exhibiting their picture postcards, Mao’s Cultural Revolution taking the form of the most infectious music, the world ending in a traffic jam, a character scarfing up yoghurt with a finger in the bathroom, two African garbage collectors reciting Lenin, our favourite film stars baffled by their new roles, an interpolated series of interview-interrogations in which ten-year-olds are asked about class struggle, and fun-loving models, about the latest decisions of the CGT, ‘la musique, c’est mon Antigone!’ – narrative deteriorating steadily all the while only to end up in 3-D or in images as thick as butterflies in front of the face.

More here.