Joshua Rothman in The New Yorker:

Try to remember life as you lived it years ago, on a typical day in the fall. Back then, you cared deeply about certain things (a girlfriend? Depeche Mode?) but were oblivious of others (your political commitments? your children?). Certain key events—college? war? marriage? Alcoholics Anonymous?—hadn’t yet occurred. Does the self you remember feel like you, or like a stranger? Do you seem to be remembering yesterday, or reading a novel about a fictional character?

Try to remember life as you lived it years ago, on a typical day in the fall. Back then, you cared deeply about certain things (a girlfriend? Depeche Mode?) but were oblivious of others (your political commitments? your children?). Certain key events—college? war? marriage? Alcoholics Anonymous?—hadn’t yet occurred. Does the self you remember feel like you, or like a stranger? Do you seem to be remembering yesterday, or reading a novel about a fictional character?

If you have the former feelings, you’re probably a continuer; if the latter, you’re probably a divider. You might prefer being one to the other, but find it hard to shift your perspective. In the poem “The Rainbow,” William Wordsworth wrote that “the Child is Father of the Man,” and this motto is often quoted as truth. But he couched the idea as an aspiration—“And I could wish my days to be / Bound each to each by natural piety”—as if to say that, though it would be nice if our childhoods and adulthoods were connected like the ends of a rainbow, the connection could be an illusion that depends on where we stand. One reason to go to a high-school reunion is to feel like one’s past self—old friendships resume, old in-jokes resurface, old crushes reignite. But the time travel ceases when you step out of the gym. It turns out that you’ve changed, after all.

More here.

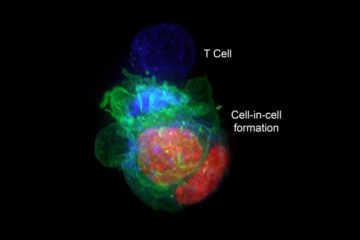

In a surprise discovery, researchers found that cells from some types of cancers escaped destruction by the immune system by hiding inside other cancer cells.

In a surprise discovery, researchers found that cells from some types of cancers escaped destruction by the immune system by hiding inside other cancer cells. Weiskrantz took a new approach with a human patient, known by the initials DB, who, after surgery to remove a growth affecting the visual cortex on the left side of his brain, was blind across the right-half field of vision. In the blind area, DB himself maintained that he had no visual awareness. Nonetheless, Weiskrantz asked him to guess the location and shape of an object that lay in this area. To everyone’s surprise, he consistently guessed correctly. To DB himself, his success in guessing seemed quite unreasonable. So far as he was concerned, he wasn’t the source of his perceptual judgments, his sight had nothing to do with him. Weiskrantz named this capacity ‘blindsight’: visual perception in the absence of any felt visual sensations.

Weiskrantz took a new approach with a human patient, known by the initials DB, who, after surgery to remove a growth affecting the visual cortex on the left side of his brain, was blind across the right-half field of vision. In the blind area, DB himself maintained that he had no visual awareness. Nonetheless, Weiskrantz asked him to guess the location and shape of an object that lay in this area. To everyone’s surprise, he consistently guessed correctly. To DB himself, his success in guessing seemed quite unreasonable. So far as he was concerned, he wasn’t the source of his perceptual judgments, his sight had nothing to do with him. Weiskrantz named this capacity ‘blindsight’: visual perception in the absence of any felt visual sensations.

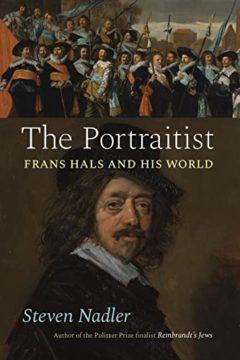

Frans Hals was born in Antwerp in around 1582, moved to Haarlem when he was three, found fame rather late, in his mid-thirties, died in 1666 – and was forgotten, at least outside his native country. The apparent lack of finish in his work made it unfashionable in the eyes of connoisseurs and collectors until interest in his paintings grew again in the mid-19th century. In 1865 Hals’s Laughing Cavalier was bought for a vast sum by Lord Hertford and exhibited in London to huge acclaim. Soon afterwards it entered the Wallace Collection.

Frans Hals was born in Antwerp in around 1582, moved to Haarlem when he was three, found fame rather late, in his mid-thirties, died in 1666 – and was forgotten, at least outside his native country. The apparent lack of finish in his work made it unfashionable in the eyes of connoisseurs and collectors until interest in his paintings grew again in the mid-19th century. In 1865 Hals’s Laughing Cavalier was bought for a vast sum by Lord Hertford and exhibited in London to huge acclaim. Soon afterwards it entered the Wallace Collection. A team of computer scientists has come up with a

A team of computer scientists has come up with a  In September 2016 I gave a lecture at Duke University: “

In September 2016 I gave a lecture at Duke University: “ Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian woman, died on September 16th in Tehran after being detained and allegedly beaten by Iran’s

Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian woman, died on September 16th in Tehran after being detained and allegedly beaten by Iran’s  The first therapeutic cancer vaccine, approved more than a decade ago, targeted prostate tumours. The treatment involves extracting antigen-presenting cells — a component of the immune system that tells other cells what to target — from a person’s blood, loading them with a marker found on prostate tumours, and then returning them to the patient. The idea is that other immune cells will then take note and attack the cancer.

The first therapeutic cancer vaccine, approved more than a decade ago, targeted prostate tumours. The treatment involves extracting antigen-presenting cells — a component of the immune system that tells other cells what to target — from a person’s blood, loading them with a marker found on prostate tumours, and then returning them to the patient. The idea is that other immune cells will then take note and attack the cancer. Before leaving Santa Fe I spent (yet another) morning at a coffeehouse. It’s an urban sort of behavior, and a Bachian one too – you might know about Zimmerman’s in Leipzig, the coffeehouse where Bach brought ensembles large and small to perform once a week. It seems to have been a chance to make some non-liturgical music, a relief from Bach’s otherwise very churchy employment.

Before leaving Santa Fe I spent (yet another) morning at a coffeehouse. It’s an urban sort of behavior, and a Bachian one too – you might know about Zimmerman’s in Leipzig, the coffeehouse where Bach brought ensembles large and small to perform once a week. It seems to have been a chance to make some non-liturgical music, a relief from Bach’s otherwise very churchy employment.

At a recent tournament sponsored by the St. Louis Chess Club, 19-year old Hans Niemann rocked the chess world by defeating grandmaster Magnus Carlson, the world’s top player. Their match was not an anticipated showdown between a senior titan and a recognized rising phenom. The upset came out of nowhere.

At a recent tournament sponsored by the St. Louis Chess Club, 19-year old Hans Niemann rocked the chess world by defeating grandmaster Magnus Carlson, the world’s top player. Their match was not an anticipated showdown between a senior titan and a recognized rising phenom. The upset came out of nowhere. They all want it: the ‘digital economy’ runs on it, extracting it, buying and selling our attention. We are solicited to click and scroll in order to satisfy fleeting interests, anticipations of brief pleasures, information to retain or forget. Information: streams of data, images, chat: not knowledge, which is something shaped to a human purpose. They gather it, we lose it, dispersed across platforms and screens through the day and far into the night. The nervous system, bombarded by stimuli, begins to experience the stressful day and night as one long flickering all-consuming series of virtual non events.

They all want it: the ‘digital economy’ runs on it, extracting it, buying and selling our attention. We are solicited to click and scroll in order to satisfy fleeting interests, anticipations of brief pleasures, information to retain or forget. Information: streams of data, images, chat: not knowledge, which is something shaped to a human purpose. They gather it, we lose it, dispersed across platforms and screens through the day and far into the night. The nervous system, bombarded by stimuli, begins to experience the stressful day and night as one long flickering all-consuming series of virtual non events.

Today “skepticism” has two related meanings. In ordinary language it is a behavioral disposition to withhold assent to a claim until sufficient evidence is available to judge the claim true or false. This skeptical disposition is central to scientific inquiry, although financial incentives and the attractions of prestige render it inconsistently realized. In a world increasingly afflicted with misinformation, disinformation, and outright lies we could use more skepticism of this sort.

Today “skepticism” has two related meanings. In ordinary language it is a behavioral disposition to withhold assent to a claim until sufficient evidence is available to judge the claim true or false. This skeptical disposition is central to scientific inquiry, although financial incentives and the attractions of prestige render it inconsistently realized. In a world increasingly afflicted with misinformation, disinformation, and outright lies we could use more skepticism of this sort.