by Mark Harvey

On the morning of July 22, 2016, an illegal campfire in Garrapata State Park near Carmel, California got out of control. Within a day, the fire grew to 2,000 acres. Within two days the fire grew to 10,000 acres. A month later the fire was at 90,000 acres and still largely uncontained. Ultimately the Forest Service and other agencies deployed thousands of firefighters and spent close to $260 million in an effort to contain it. The fire was finally “contained” three months later in October. During the three months of the fire’s life, bulldozers cut close to 60 miles of roads/firebreaks and aerial tankers dumped about 3.5 million gallons of fire retardant on the flames. The bulldozing and the aerial retardant work had little effect and what really helped put the fire out was October’s cooler temperatures and more humid air.

The fact of the matter is most wildfires go out by themselves.

The effort to fight large wildfires with expensive planes, helicopters, fire retardant, and bulldozers has been likened to fighting hurricanes or earthquakes: it’s costly and mostly futile. While developing fire-resistant lines and fireproofing buildings at the urban-forest interface can be very effective, trying to control massive blazes of tens of thousands of acres is like burning money.

Fighting wildfires is big business. When you stage thousands of firefighters in camps, you need catering services, laundry services, mobile housing, heavy equipment, and fuel. Caterers can gross millions of dollars to support large crews and local landowners make thousands of dollars renting their land and facilities for staging areas.

And so-called “preventing” fires with major tree thinning projects is really big business for the timber industry. The combination of trying to stop the major forest fires far from residential and commercial areas combined with major logging projects to thin forests before they burn has the western United States on a course of action that is destructive, counterproductive and dangerous.

Every summer, if you live in the western United States, you can expect to have days or even weeks clouded by the smoke from local and distant wildfires. It can be a mystery as to where the smoke is coming from when there are multiple fires raging at once. Here in western Colorado, we recently had haze-filled days from a distant fire in Arizona. At first I thought the haze was from a local fire as I had heard one had started nearby. But the local fire was tiny in comparison to the Arizona fire.

By now it’s evident that a warming climate has increased the intensity and acreage of wildfires on a global scale. If you want to get wonky about it, this new stage of our forests burning up is largely due to what scientists call vapor pressure deficit (VPN). In essence, a warmer, drier atmosphere sucks the moisture out of forests, grasslands, and chaparral making them far more volatile.

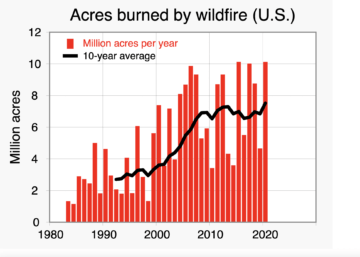

Records on total acres burned by wildfire in the US have only been kept since 1983. You can see by the accompanying graph that over the last 40 years, the average number of acres burned per ten years by wildfires has risen dramatically. In 1993 it was less than 3 million acres, in 2003 it was close to 4 million acres, in 2013 it was more than 7 million acres. In six of the ten years between 2010 and 2020, more than eight millions acres were burned by wildfire in the US.

What’s worrisome and troubling is that the Forest Service and other federal agencies seem to be missing the forest for the trees as they face managing expansive lands throughout the west. They have decided that the best solution to this new reality is by thinning forests with massive logging operations. Federal land managers believe (or purport to believe) that the real driver of the vast forest fires is excessive fuel loads, not a warming atmosphere.

In Smokescreen: Debunking Wildfire Myths to Save our Forests and our Climate (a must-read book for those interested in US forest policy and forest ecology) Dr. Chad Hanson takes us through the faulty theories and hugely destructive policies of The Forest Service in this era of climate change.

On the face of it, reducing fuel loads by removing large trees might seem like a way to reduce large fires, but as Hanson points out, recent science suggests the logging will make things worse and actually lead to hotter, more destructive burns. The same science suggests that thinning forests also destroys critical habitat for wildlife.

In his many hikes in the Duncan Canyon in California, after the 2001 Star Fire burned nearly half of the designated 8,000 acres of roadless area, Hanson noticed something interesting. In areas of the forest where the biomass and fuel loads were heavy with old-growth trees, tightly packed stands of smaller trees, and lots of downed logs, the fire had burned at a low intensity, killing just the smallest trees. Hanson noticed the same thing on subsequent forays into other forests—that fires in areas tightly packed with old-growth trees, small trees, and snags generally burned at low intensity, leaving a rich environment for wildlife and a forest that could recover quickly.

These observations flew in the face of what the Forest Service and the logging industry said about dense forests with old-growth trees needing to be thinned. Hanson and his colleagues decided to analyze the data on 1,500 fires that burned a total of 24 million acres over 30 years. What they found was that weather and climate were statistically the most important factors in determining the extent and intensity of wildfires, not forest density.

In fact, as Hanson points out, the denser forests generally burn at a lower intensity than forests that have been thinned by logging operations. The denser forest retains forest floor humidity better, offer more shade so the ground fuels don’t dry out, and also restrict wind flow. Anyone who has ever lit a fire in a wood stove knows that if you pack it too tightly with kindling or large logs, it just won’t burn well. The same principal is true in dense forests: a lack of air flow inhibits the flames.

Not only does forest thinning potentially increase the chance of forest fires, it also destroys critical wildlife habitat. The most casual hiker will notice the abundance of wildlife in the most unruly forests. While golfers may like well-groomed fairways and carefully raked sand traps our wild friends do not: they like the wild places often created by wildfires—snag forests.

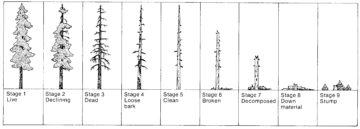

So-called “snags” in old-growth ecosystems typically make up 10 to 20 percent of all the trees present. Snags are dead standing or dead fallen trees and make for very rich habitat. Birds, in particular, thrive in snag forests but so do hundreds of other species including fungi, squirrels, raccoons, martens, reptiles, and insects.

So while forest creatures see snag forests as house, home, and pantry, the US Forest Service and the logging industry see snag forests—pre and post-fire—as something that needs thinning. And thin they do. Areas that get thinned have the snags AND lots of still live trees removed for the timber. What’s left is often the highly flammable small dead branches, trees spaced out perfectly to allow high winds to fan flames, and much less wildlife.

The Forest Service has big plans to thin our wonderful national forests based on dubious science. The recently passed infrastructure bill, which includes some useful projects, has allocated billions of dollars for wildfire mitigation; hundreds of millions of that will go toward thinning. In their 10-year plan published in January of 2022, the Forest Service announced plans to “treat” an additional 20 million acres of Forest Service land and an additional 50 million acres of federal, state, and tribal land. I don’t know how they’ve broken down the “treating” bit but we can be sure that millions of acres will see wildlife-rich snag forests destroyed and effectively sterilized.

Wildfires are with us and summers of hazy smoke out west should be expected for decades to come. There’s little doubt that a warming climate has increased extensive landscapes hit by wildfire. There are lots of things we can do at the interface of forests and urban areas to prevent towns from burning down. But the Forest Service’s plans to thin millions of acres in the next ten years in an effort at “fuel reduction” are an act of sheer folly. What the chainsaws, bulldozers, and skidders will leave behind are forests even more flammable and wildlife even more imperiled.