by Brooks Riley

Every beloved object is the center point of a paradise. —Novalis

The first full moon I saw after the procedure looked as if it might burst, like a balloon with too much helium. It was just above the horizon, fat and dark yellow —moving slowly upward to the firmament where it would later appear smaller and take on a whiter shade of pale. I could distinguish its tranquil seas, the old familiar terrain coinciding with a long abandoned memory.

The first full moon I saw after the procedure looked as if it might burst, like a balloon with too much helium. It was just above the horizon, fat and dark yellow —moving slowly upward to the firmament where it would later appear smaller and take on a whiter shade of pale. I could distinguish its tranquil seas, the old familiar terrain coinciding with a long abandoned memory.

It had been a while since I’d seen the full moon this way. For far too many moons, all I had seen were the fractured doubled contours of an indeterminate object in the night sky where the moon should have been. The problem was cataracts, or clouding of the ocular lens.

Advancing age metes out decline in increments. I hardly noticed the changes in my vision. Spending so much time on the internet, I was getting second-hand access to the world and its visual splendor and diversity through photographs and videos—none of which prepared me for the increasing inexactness that met my gaze wherever I went.

***

Even before the bandage came off, the implant’s ID card seemed to confirm it: I am a camera—with a new Zeiss lens made in Jena. Jena is back in my life.

Even before the bandage came off, the implant’s ID card seemed to confirm it: I am a camera—with a new Zeiss lens made in Jena. Jena is back in my life.

How can that be, when I’ve never visited the city, only passed through its train station on my way to nearby Weimar? As I cautiously open my left eye to a rush of fine details I couldn’t see a week ago, the first words that come to mind are Jena Paradies, the name of the train stop that always made me smile. Jena’s Paradise is a nearby park. Mine is a second chance at sight.

Jena is famous for Carl Zeiss, a builder of precision instruments for scientific study, who founded his eponymous enterprise there in 1846. From the beginning, Zeiss made it possible to see much more of the world—through better microscopes, telescopes, magnifying glasses, binoculars, and eventually camera lenses. The company, now a global entity, quietly pervades our lives, with lenses everywhere, also inside my eyes.

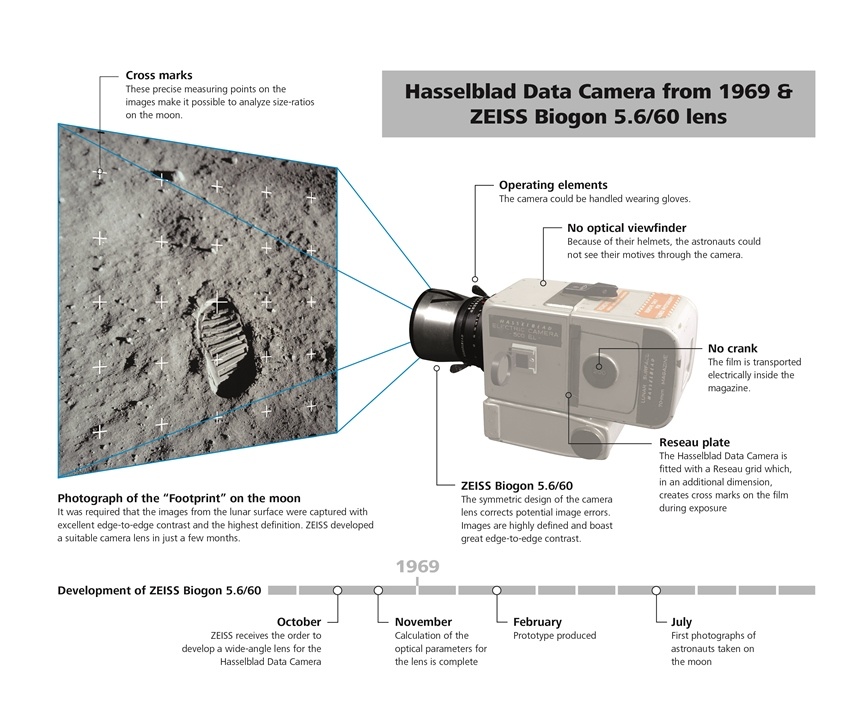

Zeiss has even been to the moon, where its lenses remain, lying face up in their Hasselblads on the lunar floor. Aldrin and Armstrong took the exposed film with them but left the cameras behind to make room for more moon rocks on the trip home. Now when I look up at the moon, I imagine those faraway lenses gazing longingly at my new ones across the spatial divide. ‘Come and get us.’

***

Synchronicity is a consequence of the algorithms of chance always humming in the background. Finding connections where none seem to exist, plumbing the archives of past experience as well as hints from the present, they tailor the timing of synchronicity for maximum poetic effect.

Accident is simply unforeseen order. —Novalis

Jena entered my life in early childhood. Every weekday for more than two years I walked across the Pont d’Iéna to play in the park of the Eiffel Tower with my friends. If France ever gets woke about its former Emperor’s warmongering, it’ll face a cluster of Jenas in Paris to be renamed—the Place d’Iéna, the Avenue d’Iéna, the Pont d’Iéna and the Metro station. As a teenager, I returned to Paris with my parents for a visit. Early on a Sunday morning, as we were leaving the hotel (the d’Iéna, of course, on the Avenue d’Iéna) the hum of a motorcade moving slowly up the deserted avenue caught our attention. It was President Eisenhower on his way somewhere. As his limo glided by, he waved to us, just as he had seven years earlier in front of the American Cathedral on the Avenue George V, when he was still a General. (I have a Zelig-like history of being waved at: On my only visit to Japan, within hours of landing, I was waved at by its emperor. But that’s another story. . .)

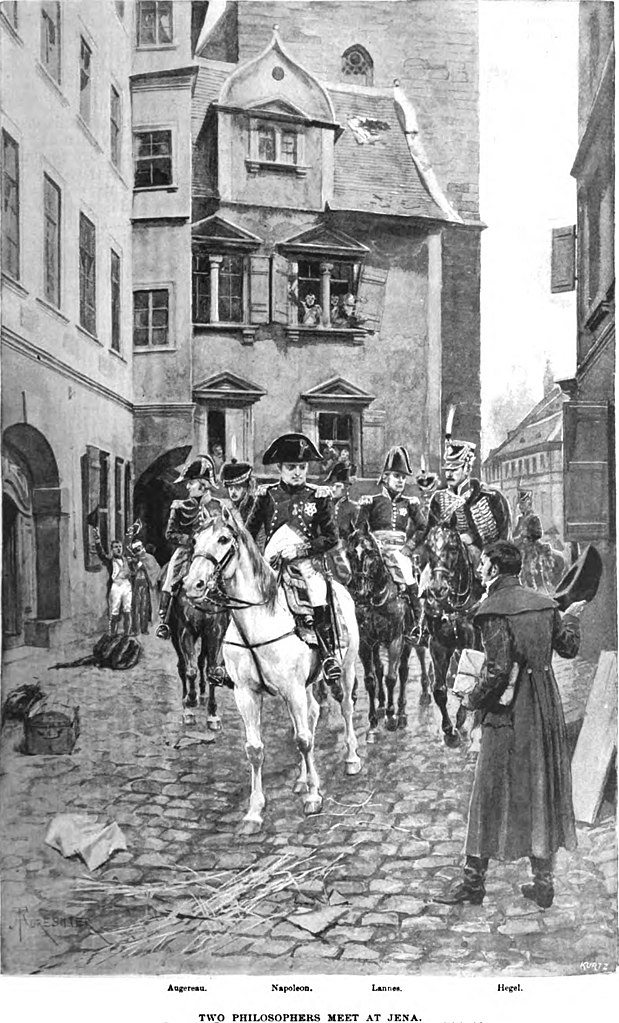

I’m sure Napoleon did not wave at the philosopher Hegel when he passed him on a street in Jena on October 13, 1806, one day before the famous Battle of Jena, but Hegel was just as starstruck as I might once have been, given my on-again-off-again interest in the problematical French icon. As he wrote to a friend:

I saw the Emperor – this world-soul – riding out of the city on reconnaissance. It is indeed a wonderful sensation to see such an individual, who, concentrated here at a single point, astride a horse, reaches out over the world and masters it … this extraordinary man, whom it is impossible not to admire.

Whoever immortalized Hegel’s encounter in this illustration knew Jena well enough to stage it in front of a local landmark, the Burgkeller, but the description as a meeting of ‘two philosophers’ is decidedly a stretch.

Hegel can’t have been unaware of the reason for Napoleon’s presence in Jena. But his head that day seemed to be in clouds that obliterated any concerns. The next day, Prussia would be trounced.

Hegel can’t have been unaware of the reason for Napoleon’s presence in Jena. But his head that day seemed to be in clouds that obliterated any concerns. The next day, Prussia would be trounced.

The current, protracted invasion of Ukraine with its barbaric disregard for civilian life or the rules of war, makes the Battle of Jena seem like a surgical strike, even if the numbers involved were staggering. The fate of Prussia was decided within a few hours, by a combined force of 95,000 that would just about fill Wembley Stadium, fighting near the town of Jena whose population at the time was ca. 5000. Jena remained unscathed.

Schiller, had he still lived, would not have cherished a chance encounter with Napoleon in Jena. Wary of the French Revolution and its anarchic aftermath, he had predicted early on that a strongman would rise to fill the power vacuum and extend his mandate across Europe. In our century, a nastier piece of work has filled the power vacuum left by the collapse of a different ancien régime-—and taken his mandate on the road. The outcome is a devastating ongoing war of attrition.

Schiller’s day job teaching history at the University of Jena coincided with his trilogy of plays, Wallenstein, which once occupied an entire semester of my life, as I struggled to prove in a term paper that he had written the plays with Napoleon in mind. The characters of Wallenstein and Napoleon are strikingly similar. Even if the timeline made it too close to call, the possibility of such a post-revolutionary upstart had been clear to Schiller. And Napoleon had already achieved fame with victories in Italy and Egypt by the time Wallenstein was completed in 1799. The difficulty in proving such a hypothesis is compounded by the fact that Schiller apparently never once put Napoleon’s name to paper, possibly as a silent protest against the admiration that others, even his friend Goethe, felt for the Corsican.

***

Were it not for The Invention of Nature, Andrea Wulf’s illuminating biography of Alexander von Humboldt (the one true world-soul), Jena might have remained little more than a few odd references in my bio, along with a weakness for Romanticism. If Jena gave me back my vision, that book helped me to see Jena in a new way. The lively chapter on Humboldt’s intense friendship with Goethe and their scientific collaborations in Jena demonstrates how Humboldt learned to find poetry and emotion in his scientific work, which was key to his immense appeal across the globe during his lifetime.

In the period between 1790 and 1806 Jena was an intellectual playground, spawning new -isms in philosophy, most importantly early Romanticism, also known as Jena Romanticism. The letters between Schiller and his friend Christian Gottfried Körner suggest a frenzy of creativity and exchanges of ideas going on. There were probably more polymaths per capita in Jena at that time than anywhere on earth—discussing, arguing, collaborating, writing, publishing, researching, and socializing. The Humboldt brothers were catalysts for new ways of thinking and knowing: Alexander, about scientific methods, and Wilhelm, about language. But there were others, poets and thinkers alike—Novalis, Fichte, Schelling, the Schlegel brothers, Herder, Hegel, Hölderlin, not forgetting Goethe, on visits from Weimar, and especially Schiller, who often played host. For a short time Jena, this lesser-known oasis of culture in the shadow of Weimar, was the ‘in’ place for an upheaval of ideas about nature, art and science.*

Jena today is a city of science and technology, but it hasn’t abandoned philosophy. This week, the Friedrich-Schiller University in Jena will host an international conference on Romanticism. And it maintains an extensive database called Gestern-Romantik-Heute, consolidating worldwide information about events and publications related to Romanticism.

Romanticism is sometimes considered a diversion from the progress-oriented rationality of the Enlightenment, or an implied rejection of liberal ideas. For me it’s the occasional refuge from the throwaway trendiness of today’s art. When I stand before Caspar David Friedrich’s masterpiece The Sea of Ice, I am certain that he saw the end coming—recognizing the awful beauty in destruction. In stark contrast to his Biedermeier-ish couples appreciating a moonrise, in this painting all that’s left of us is a shipwreck dwarfed by massive colliding slabs of ice. How prophetic he was.

Novalis asks us ‘to romanticize the world.’ I’m all for it if that gives us the impetus to save it. (Where is Humboldt when we need him most?) But my version of a Romanticism 2.0 would follow Friedrich’s pessimistic lead, as expanded by the aesthetics of destruction in the works of Anselm Kiefer, depicting a world in ruins, with only faint traces left of our existence, as the spasms of disruption caused by our kind slowly subside. In this inversion of Romanticism, where beauty and awe nevertheless endure in some form, our emotions are still grand, but anguish has replaced exaltation, as we begin the mourning phase of a loss we haven’t yet experienced.

Paradise is scattered over the whole earth, and that is why it has become so unrecognizable. —Novalis

I’ve been thinking a lot about sight. Foresight, hindsight, insight serve as important add-ons to our thinking. The time for foresight is already over. If all goes south, there won’t be an opportunity for hindsight. That leaves us with insight, a timeless version of paying attention that might still yield solutions.

The climate crisis has a dramaturgical problem. It’s not suspenseful enough. It’s slow and insidious, with few visible takeaways we haven’t already seen. An egg sizzling on a hot sidewalk in New York or New Delhi? Another iceberg dissolving into the sea? One more polar bear? If Meta or Musk were truly visionary, they would come up with novel ways to divert public attention back to what really matters, this paradise that’s about to be lost.

To romanticize the world is to make ourselves aware of the magic, mystery and wonder of the world; it is to educate the senses to see the ordinary as extraordinary, the familiar as strange, the mundane as sacred, the finite as infinite. —Novalis

I do that every morning as I hurry to the window. Now that my vision is back, the ‘ordinary’ does seem ‘extraordinary’, the ‘familiar’ has a strange new brilliance, the ‘mundane’ is somehow exotic I still can’t see what’s beyond the horizon. I still can’t see a way out of our global predicament. But curiosity has returned, and wonder at all that I do see. Maybe now’s the time to go see Jena.

We dream of travels through the universe: Isn’t the universe inside us? —Novalis

***

*As synchronicity would have it, I just learned that Andrea Wulf’s next book, coming out this fall in English and German, will be about Jena and the birth of Romanticism. I can’t wait to read it.