by Akim Reinhardt

Dreams are about questions.

Dreams are about questions.

Every dream sprouts up as an innocent question in the early morning haze. Maturing in bright sunlight, it opens up, like the petals on a flower, with vibrant new questions unfolding from the original. Then, after achieving its fulsome bloom, the dream begins to sag. No longer birthing new questions, its fading aroma and shriveling grandeur are pitied, mocked, and satirized before being ignored, a loyal few finally plucking its withered remnants and vainly trying to save the dream by pressing it between the pages of a book, eternally rendering it a dry, flat scrap of its former self.

[insert a dream here]

Generations of Americans dreamed dreams about liberty and greatness and free land and streets paved with gold, one flower after another emerging, blooming, and wilting, before finally being pressed into the scrapbook of history.

[insert the blood of settler colonialism here]

When the Great Depression and World War II were finally put to rest, the American dream bourgeoned in contrast to the Soviet nightmare. We must pursue this dream of new appliances in suburban homes, of passive participation in mainline Protestantism, of Barbie doll beach blanket bingo, of vanilla white velvet cake, lest the encroaching darkness of poverty, atheism, and red gulags overrun us. Onward Christian soldier, marching ever forward to material salvation.

[insert body snatchers here]

But when the procession moved only in tightly proscribed circles, a new generation planted a seed that questioned the dream itself. Where is America and its elusive dream?

[insert a Spirograph here] Read more »

I had a colleague, a great reader, whose favorite material was mid-century Japanese short-form realism. Frequently epistolary and often featuring at least one frame narrative, these novellas typically have as their narrator someone captivated, not to say obsessed, by a memory; and that memory, it seemed to me when I read the works my colleague lent me, is almost inevitably fed by an erotic or romantic encounter, as well as by its often calamitous sequelae.

I had a colleague, a great reader, whose favorite material was mid-century Japanese short-form realism. Frequently epistolary and often featuring at least one frame narrative, these novellas typically have as their narrator someone captivated, not to say obsessed, by a memory; and that memory, it seemed to me when I read the works my colleague lent me, is almost inevitably fed by an erotic or romantic encounter, as well as by its often calamitous sequelae.

In the early 1980’s apart from joining the September group, there were two other outside organizations I was invited to join which expanded my intellectual horizons. The first was the South Asia Committee of the Social Science Research Council in New York. This Committee planned some research projects on different topics of social science in South Asia and also gave out research fellowships and postdoctoral research grants. It gave me the opportunity to interact with some of the top scholars working in the US on South Asia, including Myron Weiner, the distinguished political scientist, Bernard Cohn, the historical anthropologist, Wendy Doniger, the Sanskrit scholar, Ralph Nicholas, cultural anthropologist of Bengal, Richard Eaton, cultural historian of medieval India, and Ronald Herring, political scientist on agrarian development in India.

In the early 1980’s apart from joining the September group, there were two other outside organizations I was invited to join which expanded my intellectual horizons. The first was the South Asia Committee of the Social Science Research Council in New York. This Committee planned some research projects on different topics of social science in South Asia and also gave out research fellowships and postdoctoral research grants. It gave me the opportunity to interact with some of the top scholars working in the US on South Asia, including Myron Weiner, the distinguished political scientist, Bernard Cohn, the historical anthropologist, Wendy Doniger, the Sanskrit scholar, Ralph Nicholas, cultural anthropologist of Bengal, Richard Eaton, cultural historian of medieval India, and Ronald Herring, political scientist on agrarian development in India. I would like at least to begin here an argument that supports the following points. First, we have no strong evidence of any currently existing artificial system’s capacity for conscious experience, even if in principle it is not impossible that an artificial system could become conscious. Second, such a claim as to the uniqueness of conscious experience in evolved biological systems is fully compatible with naturalism, as it is based on the idea that consciousness is a higher-order capacity resulting from the gradual unification of several prior capacities —embodied sensation, notably— that for most of their existence did not involve consciousness. Any AI project that seeks to skip over these capacities and to rush straight to intellectual self-awareness on the part of the machine is, it seems, going to miss some crucial steps. However, finally, there is at least some evidence at present that AI is on the path to consciousness, even without having been endowed with anything like a body or a sensory apparatus that might give it the sort of phenomenal experience we human beings know and value. This path is, namely, the one that sees the bulk of the task of becoming conscious, whether one is an animal or a machine, as lying in the capacity to model other minds.

I would like at least to begin here an argument that supports the following points. First, we have no strong evidence of any currently existing artificial system’s capacity for conscious experience, even if in principle it is not impossible that an artificial system could become conscious. Second, such a claim as to the uniqueness of conscious experience in evolved biological systems is fully compatible with naturalism, as it is based on the idea that consciousness is a higher-order capacity resulting from the gradual unification of several prior capacities —embodied sensation, notably— that for most of their existence did not involve consciousness. Any AI project that seeks to skip over these capacities and to rush straight to intellectual self-awareness on the part of the machine is, it seems, going to miss some crucial steps. However, finally, there is at least some evidence at present that AI is on the path to consciousness, even without having been endowed with anything like a body or a sensory apparatus that might give it the sort of phenomenal experience we human beings know and value. This path is, namely, the one that sees the bulk of the task of becoming conscious, whether one is an animal or a machine, as lying in the capacity to model other minds. Nestled among the impressive domes and spires of Yale University is the simple office of

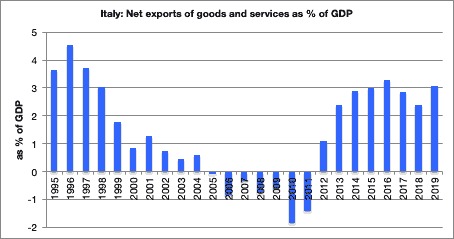

Nestled among the impressive domes and spires of Yale University is the simple office of  1. Italy is living below its means

1. Italy is living below its means Dear George Orwell,

Dear George Orwell, A plump larva the length of a paper clip can survive on the material that makes Styrofoam. The organism, commonly called a “superworm,” could transform the way waste managers dispose of one of the most common components in landfills, researchers said, potentially slowing a mounting garbage crisis that is exacerbating climate change. In a paper

A plump larva the length of a paper clip can survive on the material that makes Styrofoam. The organism, commonly called a “superworm,” could transform the way waste managers dispose of one of the most common components in landfills, researchers said, potentially slowing a mounting garbage crisis that is exacerbating climate change. In a paper  PROMINENT WHITE FEMINISTS

PROMINENT WHITE FEMINISTS Jim Al-Khalili has an enviable gig. The Iraqi-British scientist gets to ponder some of the deepest questions—What is time? How do nature’s forces work?—while living the life of a TV and radio personality. Al-Khalili hosts The Life Scientific, a show on BBC Radio 4 featuring his interviews with scientists on the impact of their research and what inspires and motivates them. He’s also presented documentaries and authored popular science books, including a novel, Sun Fall, about the crisis that unfolds when, in 2041, Earth’s magnetic field starts to fail. His latest book, The Joy of Science, is his response to a different crisis.

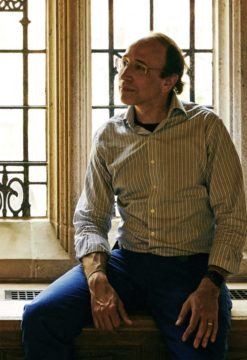

Jim Al-Khalili has an enviable gig. The Iraqi-British scientist gets to ponder some of the deepest questions—What is time? How do nature’s forces work?—while living the life of a TV and radio personality. Al-Khalili hosts The Life Scientific, a show on BBC Radio 4 featuring his interviews with scientists on the impact of their research and what inspires and motivates them. He’s also presented documentaries and authored popular science books, including a novel, Sun Fall, about the crisis that unfolds when, in 2041, Earth’s magnetic field starts to fail. His latest book, The Joy of Science, is his response to a different crisis. Justin Vassallo in Phenomenal World:

Justin Vassallo in Phenomenal World: Nóra Schultz in Tocqueville 21:

Nóra Schultz in Tocqueville 21: Kate Kirkpatrickis and Sonia Kruks in Aeon:

Kate Kirkpatrickis and Sonia Kruks in Aeon: