Ducks on a pond in Brixen, South Tyrol, in December of 2020.

Month: December 2020

A Voyage to Vancouver, Part One

by Eric Miller

To the mainland

When we climb the stairwell out of the depth of the ferry, where our car rests parked amid grimy trucks, we find taut bands of yellow plastic tape setting off the tables and benches of the observation decks. We have to sit far from other people. Someone took pleasure in this prohibitive festooning, officious pleasure perhaps but also childish joy. It is like decorating for a dance, though its effect is opposite: to un-couple us, to make all of us wallflowers. A disinvitation to the ball! Now our huge white ferry sets off from Swartz Bay—a self-willed tower. Excluding wind and sound, impervious windows mute the passing islands, each projected for us as in a theatre. The thrum of the engine pleases, supplying constant reassurance that everything is fine. Its weak, unvaried arpeggio would seem to guarantee the integrity of our own simmering organic system. A humming machine befriends us. It defends and supports us by a flattering yet ideally stable mimesis of our private vibe, our autonomic hubbub.

The Salish Sea imparts not the least sensation of rocking to the vessel, the vessel is so big relative to the swell. When I see that yellow tape, however, I always worry about the disposal of it. It consists of a sort of plastic that stretches thin, but is reluctant to disappear. Round and round the globe like longitudes and latitudes, such tape persists impertinently after the end of perceived emergency that—once upon a time, it will have been so long ago!—cordoned off part of the habitable world from the rest. The rationale is Covid-19.

From where I sit like a moviegoer, I watch the water. Without pangs of apocalypse or a sense of my witness being in any way representative, my contemplation accumulates the fewest seabirds I have ever seen, the fewest birds in general I have ever seen, between Swartz Bay and Tsawwassen. Three gulls. Three cormorants. On other occasions Bald Eagles have been as common as crows, murres dove before the bland advance of our blanched castle, rafts of ducks, mergansers, all nonchalance, paddled a derisive minimal distance from our apparition. The ocean almost stagnates, preserving the bubbles of our ferry’s hours-before previous passage as though so surpassingly enervated as not to prick them. Flabby Neptune’s trident is too dull, this August day, to lance any eruption. We can see how little the skipper deviates from a set course by these viscous-looking residues. The brisk ship hurries to escape an ambient torpor. Read more »

FILM REVIEW: Beautiful, Befuddled Blarney via Broadway

by Alexander C. Kafka

Can the moon strike twice? Sadly, no.

The question hovers over John Patrick Shanley’s new film Wild Mountain Thyme because it aims for the same sort of bittersweet heartache seasoned with gritty and eccentric comedic beats that characterized his Oscar-winning script for Moonstruck (1987).

The grit then was of the Brooklyn Heights variety while now it is West Irish farm dirt. The story, adapted from Shanley’s 2014 play Outside Mullingar, was inspired by a trip the Bronx-born writer took with his octogenarian father to the family’s County Westmeath homestead. Shanley was smitten with its denizens’ quirky, homey warmth and he translates that into a stew of poetically depressive, circular philosophizing centered around a thwarted romance between two neighboring farmers, Rosemary Muldoon and Anthony Reilly.

The result is a beautiful, somewhat patronizing, nonsensical muddle, in large part because it is irritatingly unclear what exactly does thwart the romance. The answers, near as we can tell, are Anthony’s self-doubt, inertia, and psychological instability and Rosemary’s pride. He is “touched,” as country folk often are on Broadway — talking to himself and carrying a sensitive secret. The long-suffering Rosemary has been waiting decades for him to make a move and subsumes her longing in cigarettes and a stoney-faced stiffness. On the rare occasion that she smiles, we fear that her visage may shatter. Read more »

A Remedy for Tired Wine Tasting Notes

by Dwight Furrow

Last month I argued that wine tasting notes don’t give us much information about how a wine tastes. Most tasting notes consist of a list of aromas that are typical for the kind of wine being described. But we can’t infer much about quality or distinctiveness from a list of typical aromas. Whether a Cabernet Sauvignon shows black cherry or blackberry just isn’t very important for one’s enjoyment. The basic problem with this approach to describing wine is that a list of individual elements does not reveal how these elements interact to form a whole. We get pleasure from a wine because the elements—aromas, flavors, and textures—form complex relations that we taste as a unity. But our wine vocabulary does a poor job of describing that unity.

Last month I argued that wine tasting notes don’t give us much information about how a wine tastes. Most tasting notes consist of a list of aromas that are typical for the kind of wine being described. But we can’t infer much about quality or distinctiveness from a list of typical aromas. Whether a Cabernet Sauvignon shows black cherry or blackberry just isn’t very important for one’s enjoyment. The basic problem with this approach to describing wine is that a list of individual elements does not reveal how these elements interact to form a whole. We get pleasure from a wine because the elements—aromas, flavors, and textures—form complex relations that we taste as a unity. But our wine vocabulary does a poor job of describing that unity.

This unhelpful approach to tasting notes has a history. Aromas are caused by compounds in wine that can be objectively determined. Thus, there are well-established causal relationships between compounds objectively “in the wine” and the subjective impressions of well-trained tasters that enable standards of correctness to be applied to wine tasting. These standards provide the wine community with a definable, teachable skill grounded in facts about wine. The development of that skill and the standards of correctness that enable it is a worthy goal, but this tasting model leaves the aesthetic experience of wine out of the picture.

What then is the alternative? Read more »

Performing Modernity: You don’t have to look far to find the dark side of Dubai

Rafia Zakaria in The Baffler:

THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES has worked long and hard at looking like the West—even better than the best. The world’s tallest building, with its glistening spire, looms over the shoreline of the gleaming city of Dubai, proof of the Emiratis’ technocratic zeal. The streets are clean; a brown or black person is always nearby to pick up any errant piece of litter. For entertainment, there are bars and clubs where liquor flows much like it does in New York or London or any place that draws the young and the affluent. Blazing lights shine from malls full of wares from around the world: perfumes that cost hundreds of dollars, couture houses that make their own statement by refusing to pin prices, cars that cost more than a small suburban home in the American Midwest.

THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES has worked long and hard at looking like the West—even better than the best. The world’s tallest building, with its glistening spire, looms over the shoreline of the gleaming city of Dubai, proof of the Emiratis’ technocratic zeal. The streets are clean; a brown or black person is always nearby to pick up any errant piece of litter. For entertainment, there are bars and clubs where liquor flows much like it does in New York or London or any place that draws the young and the affluent. Blazing lights shine from malls full of wares from around the world: perfumes that cost hundreds of dollars, couture houses that make their own statement by refusing to pin prices, cars that cost more than a small suburban home in the American Midwest.

There are many takers for Dubai’s performance of modernity, gussied up as it is in the wrappings of unfettered abundance. You can see the glee on the faces of Western travelers as soon as they arrive, as they roam from one duty-free store full of candy and makeup and watches and so much else to the next. Here they can play and buy and evade taxes and gather up goodies like never before. Whatever the condition of the consumer markets of their origins, here capitalism rules, and lays before them all the status symbols, all the gewgaws and gadgets, that their hearts desire. There are multiple Apple stores, and Tesla dealerships too. If you’ve brought the cash—and the corrupt grifters and former dictators and dynastic rulers have—you can pour it into all this, or into Dubai’s internationally appealing real estate market.

And even while the world, particularly the world still romancing liberal democracy, knows that Dubai’s dalliance with modernity is a farce, the UAE continues to get a free pass.

More here.

Book Review: The Power of Chance in Shaping Life and Evolution

Dan Falk in Undark:

It is to biologist Sean B. Carroll’s credit that he’s found a way of taking a puzzle that could easily fill volumes (and probably has filled volumes), and presenting it to us in a slim, non-technical, and fun little book, “A Series of Fortunate Events: Chance and the Making of the Planet, Life, and You.”

It is to biologist Sean B. Carroll’s credit that he’s found a way of taking a puzzle that could easily fill volumes (and probably has filled volumes), and presenting it to us in a slim, non-technical, and fun little book, “A Series of Fortunate Events: Chance and the Making of the Planet, Life, and You.”

Carroll (not to be confused with physicist and writer Sean M. Carroll) gets the ball rolling with an introduction to the key concepts in probability and game theory, but quickly moves on to the issue at the heart of the book: the role of chance in evolution. Here we meet a key historical figure, the 20th-century French biochemist Jacques Monod, who won a Nobel Prize for his work on genetics. Monod understood that genetic mutations play a critical role in evolution, and he was struck by the random nature of those mutations.

Carroll quotes Monod: “Pure chance, absolutely free and blind, at the very root of the stupendous edifice of evolution: This central concept of modern biology is no longer one among other possible or even conceivable hypotheses. It is today the sole conceivable hypothesis, the only one that squares with observed and tested fact.”

More here.

The Politics of Cultural Appropriation

Brian Morton in Dissent:

I first heard the phrase “Stay in your lane” a few years ago, in a writing workshop I was teaching. We were talking about a story that a student in the group, an Asian-American man, had written about an African-American family.

I first heard the phrase “Stay in your lane” a few years ago, in a writing workshop I was teaching. We were talking about a story that a student in the group, an Asian-American man, had written about an African-American family.

There was a lot to criticize about the story, including an abundance of clichés about the lives of Black Americans. I had expected the class to offer suggestions for improvement. What I hadn’t expected was that some students would tell the writer that he shouldn’t have written the story at all. As one of them put it, if a member of a relatively privileged group writes a story about a member of a marginalized group, this is an act of cultural appropriation and therefore does harm.

Arguments about cultural appropriation make the news every month or two. Two women from Portland, after enjoying the food during a trip to Mexico, open a burrito cart when they return home but, assailed by online activists, close their business within months. A yoga class at a university in Canada is shut down by student protests. The author of a young-adult novel, criticized for writing about characters from backgrounds different from his own, apologizes and withdraws his book from circulation. Such a wide variety of acts and practices is condemned as cultural appropriation that it can be hard to tell what cultural appropriation is.

More here.

How have philosophers responded to the pandemic?

Santiago Zabala at Al Jazeera:

Unlike the September 11 attacks and the 2008 financial crisis – the first two supposedly global events of the 21st century – this pandemic has not spared anyone anywhere, and its consequences will continue to be felt for decades in every corner of the world.

Unlike the September 11 attacks and the 2008 financial crisis – the first two supposedly global events of the 21st century – this pandemic has not spared anyone anywhere, and its consequences will continue to be felt for decades in every corner of the world.

The global nature of this emergency has compelled everyone to contribute to the efforts to end it either professionally or in a personal capacity. While immunologists, doctors, and nurses became indispensable in the quest to develop vaccines and assist patients, others contributed simply by wearing masks and offering to help their vulnerable neighbours during lockdowns.

But how have philosophers contributed? Can “the love for wisdom”, as it is classically defined, make any difference in a pandemic?

More here.

‘URDU’ Not a Language Name but the City of Shajahanabad

Ather Farouqui in Maeeshat:

Hindi—the original name of the language now known as Urdu—and modern Hindi are two distinct languages. Despite being a fairly new language, notions regarding Urdu’s origins and history are as hotly debated amongst the public at large as among scholars and linguists. Interestingly, the name Urdu gained currency circa 1857, with the formal cessation of Mughal rule. Hindi was the name commonly used until the second decade of the 20th century by none other than Iqbal, a poet whose poetry is overtly Islamic. His use of ‘Hindi’, instead of ‘Urdu’, gives lie to determined efforts, after the establishment of the Muslim League in 1903, to paint Urdu as the language of Muslims, as opposed to modern Hindi as the language of Hindus. Urdu would then be utilised to mobilise Muslim support for a new country. The publication of Shamsur Rahman Faruqi’s seminal work, Urdu ka Ibtedaee Zamana: Adabi Tarikh o Tahzib ke Pahlu (1999), followed by its original English version (Early Urdu Literary Culture and History [2001]), compelled the revision of many current and honoured notions about early Urdu and its literary culture. In many ways, it was a pioneering work which needs to be revisited. The book demolished myths and assumptions about the early history of the language as it developed in and around Delhi from the late 17th century onwards. It provided new information—not yet challenged—about the origin of the language name ‘Urdu’, and many other aspects of Urdu’s literary history.

Hindi—the original name of the language now known as Urdu—and modern Hindi are two distinct languages. Despite being a fairly new language, notions regarding Urdu’s origins and history are as hotly debated amongst the public at large as among scholars and linguists. Interestingly, the name Urdu gained currency circa 1857, with the formal cessation of Mughal rule. Hindi was the name commonly used until the second decade of the 20th century by none other than Iqbal, a poet whose poetry is overtly Islamic. His use of ‘Hindi’, instead of ‘Urdu’, gives lie to determined efforts, after the establishment of the Muslim League in 1903, to paint Urdu as the language of Muslims, as opposed to modern Hindi as the language of Hindus. Urdu would then be utilised to mobilise Muslim support for a new country. The publication of Shamsur Rahman Faruqi’s seminal work, Urdu ka Ibtedaee Zamana: Adabi Tarikh o Tahzib ke Pahlu (1999), followed by its original English version (Early Urdu Literary Culture and History [2001]), compelled the revision of many current and honoured notions about early Urdu and its literary culture. In many ways, it was a pioneering work which needs to be revisited. The book demolished myths and assumptions about the early history of the language as it developed in and around Delhi from the late 17th century onwards. It provided new information—not yet challenged—about the origin of the language name ‘Urdu’, and many other aspects of Urdu’s literary history.

…Urdu speakers suffered marginalisation, followed by alienation after Partition. The slogan ‘Hindu–Hindi–Hindustani’ was concocted in the early part of the 20th century and this helped reinforce the specious belief that Hindi was the language of Hindus and Urdu was, or ought to be, the language of Muslims. Tragically, no one—Hindu or Muslim—opposed the spurious name Urdu for the language then called Hindi/Rekhta. Public opinion in India at that time was not at all conscious, even dimly, of the consequences of this new baptism. A large number of Muslims, and some Hindus, opposed the creation of Hindi as a new language, but the matter rapidly became politicised.

More here.

Freedom Came in Cycles

Pamela Sneed in The Paris Review:

Uncle Vernon was cool, tall, hazel-eyed, and brown-skinned. He dressed in the latest fashions and wore leather long after the sixties. Of all of my father’s three brothers, Vernon was the artist—a painter and photographer in a decidedly nonartistic family. To demonstrate his flair for the dramatic and avant-garde, his apartment was stylishly decorated. It showcased a faux brown suede, crushed velvet couch with square rectangular pieces that sectioned off like geography, accentuated by a round glass coffee table with decorative steel legs. It was pulled together by a large seventies organizer and stereo that nearly covered the length of an entire wall. As a final touch, dangling from the shelves was a small collection of antique long-legged dolls. This was my uncle and memories of his apartment were never so clear as the day I headed there with my first boyfriend, Shaun Lyle.

Uncle Vernon was cool, tall, hazel-eyed, and brown-skinned. He dressed in the latest fashions and wore leather long after the sixties. Of all of my father’s three brothers, Vernon was the artist—a painter and photographer in a decidedly nonartistic family. To demonstrate his flair for the dramatic and avant-garde, his apartment was stylishly decorated. It showcased a faux brown suede, crushed velvet couch with square rectangular pieces that sectioned off like geography, accentuated by a round glass coffee table with decorative steel legs. It was pulled together by a large seventies organizer and stereo that nearly covered the length of an entire wall. As a final touch, dangling from the shelves was a small collection of antique long-legged dolls. This was my uncle and memories of his apartment were never so clear as the day I headed there with my first boyfriend, Shaun Lyle.

It was the eighties, late spring, the year king of soul Luther Vandross debuted his blockbuster album, Never Too Much, with moving songs about love. If ever there was a moment in my life that I felt free, unsaddled by life’s burdens, and experienced, in the words of an old cliché, “winds of possibility,” it had to be the time with Shaun Lyle heading upstairs to my uncle’s house as Luther Vandross blared soulfully out from the stereo, “A house is not a home.”

Of course Shaun was not the first or last person with whom I’d experienced feelings or sensations of unbridled freedom. Like seasons, freedom came in cycles, like in fall, in college with no money, chumming around with my best friend and school buddy Michael. We spent late afternoons wandering Manhattan’s East and West Village, searching for cheap drinks and pizza at happy hour specials, ecstatic in our poverty. Michael was a blond Irish Catholic punk rocker from Boston. We met when I was an RA at the New School’s Thirty-Fourth Street dorms at the YMCA. They were narrow, tiny rooms like closets and some floors served as a hostel for homeless men. Punk music blared from Michael’s room. I would knock on the door, commanding, “Turn it down.” Eventually, we united over the fact that he put a towel under the door to block the smell of weed smoke that frequently leaked from his room into the hallway. Michael and I were both writers, astute critics, and teacher’s pets. In fiction-writing class, we formed a power block. No piece of writing done by another student escaped our scathing critique. Professors deferred to us. “Michael, Pamela, what do you think?”

More here.

Helen LaFrance (1919 – 2020)

Othella Dallas (1925 – 2020)

Camilla Wicks (1928 – 2020)

The European Coup

Perry Anderson in the LRB:

Perry Anderson in the LRB:

By repute, literature on the European Union and its prehistory is notoriously intractable: dull, technical, infested with jargon – matter for specialists, not general readers. From the beginning, however, beneath an unattractive surface it developed considerable intellectual energy, even ingenuity, as contrasting interpretations and standpoints confronted one another. But for some sixty years after the Schuman Plan was unveiled in 1950, there was a striking displacement in this body of writing. Virtually without exception, the most original and influential work was produced not by Europeans, but Americans. Whether the angle of attack was political science, economics, law, sociology, philosophy or history, the major contributions – Haas, Moravcsik, Schmitter, Eichengreen, Weiler, Fligstein, Siedentop, Gillingham – came from the United States, with a singleton from England before its accession to the Common Market, in the pioneering reconstruction of Alan Milward.

This has finally changed. In the last decade Europe has generated a set of thinkers about its integration who command the field, while the US, increasingly absorbed in itself, has largely vacated it. Among these, one stands out. By reason of both the reception and the quality of his work, the Dutch philosopher-historian Luuk van Middelaar can be termed, in Gramsci’s vocabulary, the first organic intellectual of the EU. Though related, applause and achievement are not the same. The Passage to Europe: How a Continent Became a Union, which catapulted van Middelaar to fame and the precincts of power, is a remarkable work. The tones in which it was received are of another order. ‘There are books,’ a Belgian reviewer declared, ‘before which a chronicler is reduced to a single form of commentary: an advertisement.’ The author himself has posted forty encomia on his website, in seven or eight languages, tributes ransacking the lexicon of admiration: ‘supremely erudite’, ‘brilliant’, ‘beautifully written’, ‘a gripping narrative of personalities and events that reads like a Bildungsroman’, ‘all the fields of human knowledge and culture are convoked in abounding richness’, ‘near Voltairean’, ‘a Treitschke with the tongue of Foucault’. Even the austere European Journal of International Law thought it ‘read like a thriller’.

More here.

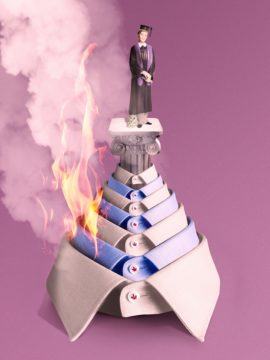

Educated Fools

Thomas Geoghegan in The New Republic:

Thomas Geoghegan in The New Republic:

Here’s a little thought experiment: What would happen if, by a snap of the fingers, white racism in America were to disappear? It might be that the black and Latino working class would be voting for Trump, too. Then we Democrats would have no chance in 2020. We often tell ourselves: “Oh, we lost just the white working class because of race.” But the truth might be something closer to this: “It’s only because of race that we have any part of the working class turning out for us at all.”

How many of us in the party’s new postgraduate leadership caste have even a single friendship, a real one, of two equals, with any man or woman who is just a high school graduate? It’s hard to imagine any Democrat in either House or Senate who did not go beyond a high school diploma. (And no, I am not talking about Harvard dropouts Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg.)

Still, it’s unthinkable that the college-educated base of the party would trust a high school graduate without a four-year degree to run for or hold a serious office. We don’t trust them, and would never vote for one of them. Why should they trust or vote for one of us?

In Nyāya philosophy only some debates are worth having

Malcolm Keating in Psyche:

Malcolm Keating in Psyche:

In premodern India, debates were entertainment in courtly settings, a sport for profiteers and clever men who enjoyed a quick turn of phrase or put-down. Successful debaters gained followers, fame, even wealth. Those pragmatic aims intertwined with nobler ones: religious believers and nonbelievers debated over deep religious truths. Both inside and outside religious traditions, participants sparred over controversies with significant social implications. Even the efficacy of medical cures was hard-fought in the debate arena.

During the 9th to 10th century CE, Vācaspati Miśra, an Indian philosopher who was part of a Hindu tradition called ‘Nyāya’ (or ‘reason’) argued that debate benefits society when it aims for truth. He thought, too, that debate helps us humans achieve ultimate happiness in our short, fragile and often painful human lives. But if debate has such noble aims, should we care about winning or losing? And if debate leads us to the truth, should we always debate everyone, everywhere? To understand Vācaspati’s answer, we must first understand the Nyāya philosophy of debate.

For Nyāya philosophers, we acquire ultimate happiness by ending the self’s painful cycle of rebirth, its journey from life to life, always bound to our past actions. Before we can end this cycle, we must rid ourselves of ethical vices. And this requires knowing the truth.

More here.

The Future of New York

A conversation between Molly Crabapple, Deborah Eisenberg, Michael Greenberg, Hari Kunzru, and Jana Prikryl:

Divided Over the Extraction Economy: An Conversation with Thea Riofrancos

Jess Bergman, David Rieff, & Ethan Taubes discuss “Divorcing,” by Susan Taubes

Gerhard Richter’s Birkenau Paintings

Robert Rubsam at Commonweal:

In the summer of 1944, a camera was smuggled out of Auschwitz. Inside it was a roll of film with four images from the gas chambers at Birkenau, taken by members of the Jewish Sonderkommando. These photos were distributed worldwide by the Polish resistance. Two of them appear to have been taken in quick succession, discreetly, from within a shadowed doorframe. The other pair, one of which is blurred, appear to have been shot at the hip from a distance. The photos show Jewish women stripping before the gas chamber, and dead bodies waiting to be incinerated. White smoke billows as other bodies burn.

In the summer of 1944, a camera was smuggled out of Auschwitz. Inside it was a roll of film with four images from the gas chambers at Birkenau, taken by members of the Jewish Sonderkommando. These photos were distributed worldwide by the Polish resistance. Two of them appear to have been taken in quick succession, discreetly, from within a shadowed doorframe. The other pair, one of which is blurred, appear to have been shot at the hip from a distance. The photos show Jewish women stripping before the gas chamber, and dead bodies waiting to be incinerated. White smoke billows as other bodies burn.

In 2014, the German painter Gerhard Richter sought to make a statement on the Holocaust. He copied these stark black-and-white images onto four monumental canvases, first in pencil, then in oil. And then he began to cover them.

more here.