by Usha Alexander

[This is the first in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. All the articles in this series can be read here.]

In 1997, I was living on Ambae, a tiny, tropical island in the western South Pacific. Rugged, jungle-draped, steamy, volcanic Ambae belongs to Vanuatu, an archipelago nation stretching some 540 miles roughly between Fiji and Papua New Guinea. There, under corrugated tin roofs, in the cinderblock classrooms of a small, residential school, I taught science to middle- and high-schoolers as a Peace Corps volunteer.

In 1997, I was living on Ambae, a tiny, tropical island in the western South Pacific. Rugged, jungle-draped, steamy, volcanic Ambae belongs to Vanuatu, an archipelago nation stretching some 540 miles roughly between Fiji and Papua New Guinea. There, under corrugated tin roofs, in the cinderblock classrooms of a small, residential school, I taught science to middle- and high-schoolers as a Peace Corps volunteer.

That December, the rainy season was in full force, with heavy downpours most afternoons, lasting sometimes long into the night. Never before had I, and never again would I, witness rains like those, where the water poured straight down, not in drops, but in globs and sheets. Standing in it felt like standing under a waterfall; I’d catch myself stepping forward or back, left or right, in an attempt to get out from under the flow, but it was everywhere. It seemed impossible that the sky could hold so much water, constricting summer’s broad daylight to a sodden gloaming.

One evening, during such a downpour, I left a teachers’ year-end potluck to return to my room—one in a row of tiny, concrete flats for the school’s single female staff. Mine was not much more than 100 yards away across an open lawn, which was now filled with ankle-deep water flowing gently down the long campus green toward the sea. As this was not my first deluge, I wasn’t concerned by the prospect of a routine water-logging; it was only water, after all, and not at all cold. The only problem was that the rains had washed away all light into a blind, enveloping darkness. I knew that once I stepped into it I would become disembodied, aware of my limbs only through my untrained sense of proprioception. How dependent we are upon the faculty of sight, even to know where we end and the external world begins.

Read more »

Someday, most likely, we will encounter life that is not as we know it. We might find it elsewhere in the universe, we might find it right here on Earth, or we might make it ourselves in a lab. Will we know it when we see it? “Life” isn’t a simple unified concept, but rather a collection of a number of life-like properties. I talk with astrobiologist Stuart Bartlett, who (in collaboration with Michael Wong) has proposed a new way of thinking about life based on four pillars: dissipation, autocatalysis, homeostasis, and learning. Their framework may or may not become the standard picture, but it provides a useful way of thinking about what we expect life to be.

Someday, most likely, we will encounter life that is not as we know it. We might find it elsewhere in the universe, we might find it right here on Earth, or we might make it ourselves in a lab. Will we know it when we see it? “Life” isn’t a simple unified concept, but rather a collection of a number of life-like properties. I talk with astrobiologist Stuart Bartlett, who (in collaboration with Michael Wong) has proposed a new way of thinking about life based on four pillars: dissipation, autocatalysis, homeostasis, and learning. Their framework may or may not become the standard picture, but it provides a useful way of thinking about what we expect life to be.

Conservatives once tried to legislate what went on in your bedroom; now it’s the left that obsesses over sexual codicils, not just for the bedroom but everywhere. Right-wingers from time to time made headlines campaigning against everything from The Last Temptation of Christ to “Fuck the Police,” though we laughed at the idea that Ice Cube made cops literally unsafe, and it was understood an artist had to do something fairly ambitious, like piss on a crucifix in public, to get conservative protesters off their couches.

Conservatives once tried to legislate what went on in your bedroom; now it’s the left that obsesses over sexual codicils, not just for the bedroom but everywhere. Right-wingers from time to time made headlines campaigning against everything from The Last Temptation of Christ to “Fuck the Police,” though we laughed at the idea that Ice Cube made cops literally unsafe, and it was understood an artist had to do something fairly ambitious, like piss on a crucifix in public, to get conservative protesters off their couches. In the Lateness of the World

In the Lateness of the World Anocha Suwichakornpong’s second feature-length film, By the Time it Gets Dark, is ostensibly a story about the brutal crackdown on student demonstrators at Thammasat University in Bangkok in 1976—the year of the filmmaker’s birth, forty years before the film was released—but its unpredictable, twisting narrative doubles back on itself in such strange ways that it becomes an interrogation of collective memory, a questioning of the role of history in contemporary Southeast Asia. The premise appears simple: two women arrive at an isolated house in the countryside, relieved to be there yet not entirely at ease with each other as they admire the spectacular views of the dry northern landscape. They have the clothes and demeanor of Bangkok dwellers, and we soon learn that they are there to tell the story of the Thammasat University killings. Taew, the older woman, was a leading figure in the student protests of the time, and has since become a celebrated writer. Ann, the younger, is a filmmaker, and spends the following days organizing oddly formal interviews with Taew, recorded on her camera, trying to piece together enough information to write a screenplay for a film based on the killings.

Anocha Suwichakornpong’s second feature-length film, By the Time it Gets Dark, is ostensibly a story about the brutal crackdown on student demonstrators at Thammasat University in Bangkok in 1976—the year of the filmmaker’s birth, forty years before the film was released—but its unpredictable, twisting narrative doubles back on itself in such strange ways that it becomes an interrogation of collective memory, a questioning of the role of history in contemporary Southeast Asia. The premise appears simple: two women arrive at an isolated house in the countryside, relieved to be there yet not entirely at ease with each other as they admire the spectacular views of the dry northern landscape. They have the clothes and demeanor of Bangkok dwellers, and we soon learn that they are there to tell the story of the Thammasat University killings. Taew, the older woman, was a leading figure in the student protests of the time, and has since become a celebrated writer. Ann, the younger, is a filmmaker, and spends the following days organizing oddly formal interviews with Taew, recorded on her camera, trying to piece together enough information to write a screenplay for a film based on the killings. The other day I caught myself reminiscing about high school with a kind of sadness and longing that can only be described as nostalgia. I felt imbued with a sense of wanting to go back in time and re-experience my classroom, the gym, the long hallways. Such bouts of nostalgia are all too common, but this case was striking because there is something I know for sure: I hated high school. I used to have nightmares, right before graduation, about having to redo it all, and would wake up in sweat and agony. I would never, ever like to go back to high school. So why did I feel nostalgia about a period I wouldn’t like to relive? The answer, as it turns out, requires we rethink our traditional idea of nostalgia.

The other day I caught myself reminiscing about high school with a kind of sadness and longing that can only be described as nostalgia. I felt imbued with a sense of wanting to go back in time and re-experience my classroom, the gym, the long hallways. Such bouts of nostalgia are all too common, but this case was striking because there is something I know for sure: I hated high school. I used to have nightmares, right before graduation, about having to redo it all, and would wake up in sweat and agony. I would never, ever like to go back to high school. So why did I feel nostalgia about a period I wouldn’t like to relive? The answer, as it turns out, requires we rethink our traditional idea of nostalgia. The timing couldn’t have been worse. In March, just as Thailand’s coronavirus outbreak began to ramp up, three hospitals in Bangkok announced that they had suspended testing for the virus because they had run out of reagents. Thai researchers rushed to help the country’s clinical laboratories meet the demand. Looking for affordable and easy-to-use tests, systems biologist Chayasith (Tao) Uttamapinant at the Vidyasirimedhi Institute of Science and Technology in Rayong reached out to an old acquaintance: CRISPR co-discoverer Feng Zhang, who had been developing an assay for the coronavirus inspired by the gene-editing technology.

The timing couldn’t have been worse. In March, just as Thailand’s coronavirus outbreak began to ramp up, three hospitals in Bangkok announced that they had suspended testing for the virus because they had run out of reagents. Thai researchers rushed to help the country’s clinical laboratories meet the demand. Looking for affordable and easy-to-use tests, systems biologist Chayasith (Tao) Uttamapinant at the Vidyasirimedhi Institute of Science and Technology in Rayong reached out to an old acquaintance: CRISPR co-discoverer Feng Zhang, who had been developing an assay for the coronavirus inspired by the gene-editing technology.

On November 11, 2019, I wrote a

On November 11, 2019, I wrote a  In 1997, I was living on Ambae, a tiny, tropical island in the western South Pacific. Rugged, jungle-draped, steamy, volcanic Ambae belongs to Vanuatu, an archipelago nation stretching some 540 miles roughly between Fiji and Papua New Guinea. There, under corrugated tin roofs, in the cinderblock classrooms of a small, residential school, I taught science to middle- and high-schoolers as a Peace Corps volunteer.

In 1997, I was living on Ambae, a tiny, tropical island in the western South Pacific. Rugged, jungle-draped, steamy, volcanic Ambae belongs to Vanuatu, an archipelago nation stretching some 540 miles roughly between Fiji and Papua New Guinea. There, under corrugated tin roofs, in the cinderblock classrooms of a small, residential school, I taught science to middle- and high-schoolers as a Peace Corps volunteer.

In the Age of Trump, the banality of evil can perhaps best be defined as unfettered self-interest. Banal because everyone has self-interest, and because American culture expects and even celebrates its most gratuitous pursuits and expressions. Evil because, when unchecked, self-interest leads not only to intolerable disparities in wealth and power, but eventually the erosion of democratic norms.

In the Age of Trump, the banality of evil can perhaps best be defined as unfettered self-interest. Banal because everyone has self-interest, and because American culture expects and even celebrates its most gratuitous pursuits and expressions. Evil because, when unchecked, self-interest leads not only to intolerable disparities in wealth and power, but eventually the erosion of democratic norms. I may rise in the morning and notice that a long overdue spring rainfall has revived the flagging vegetation in my kitchen garden. I may give thanks to an unseen, benevolent power for this respite from a protracted and wasting drought. And I may record in my journal: “The heavens cannot horde the juice eternal / The sun draws from the thirsty acres vernal.” In such exercises, I will not have practised rigorous inquiry into the causes of things; I will not have subscribed to any particular view of the metaphysical; and I will certainly not have produced literature. But I will have replicated the conditions for the birth of science, as sketched by Geoffrey Lloyd in his account of the pre-Socratic philosophers, the first thinkers (at least in the Western world) to consider natural phenomena as distinct from the supernatural, however devoutly they may have believed in the latter; and who frequently set down their observations, theories and conclusions in formal language. For my observation of a natural phenomenon (rain and its effect on plant life), while not methodical, would bespeak a willingness to collect and consider empirical data unconstrained by superstitious tradition, and would not necessarily be contradicted by my ensuing prayer of gratitude to a supernatural force; and the verse elaboration of my findings into a speculative theory would not consign them to the realm of poetry (or even doggerel), but would merely represent a formal convention, whose forebears include Hesiod, Xenophanes, Lucretius and Vergil.

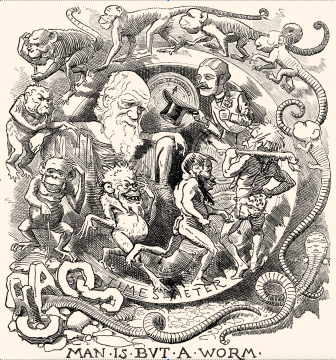

I may rise in the morning and notice that a long overdue spring rainfall has revived the flagging vegetation in my kitchen garden. I may give thanks to an unseen, benevolent power for this respite from a protracted and wasting drought. And I may record in my journal: “The heavens cannot horde the juice eternal / The sun draws from the thirsty acres vernal.” In such exercises, I will not have practised rigorous inquiry into the causes of things; I will not have subscribed to any particular view of the metaphysical; and I will certainly not have produced literature. But I will have replicated the conditions for the birth of science, as sketched by Geoffrey Lloyd in his account of the pre-Socratic philosophers, the first thinkers (at least in the Western world) to consider natural phenomena as distinct from the supernatural, however devoutly they may have believed in the latter; and who frequently set down their observations, theories and conclusions in formal language. For my observation of a natural phenomenon (rain and its effect on plant life), while not methodical, would bespeak a willingness to collect and consider empirical data unconstrained by superstitious tradition, and would not necessarily be contradicted by my ensuing prayer of gratitude to a supernatural force; and the verse elaboration of my findings into a speculative theory would not consign them to the realm of poetry (or even doggerel), but would merely represent a formal convention, whose forebears include Hesiod, Xenophanes, Lucretius and Vergil. Rutger Bregman’s Humankind: A Hopeful History is a clearly written argument if ever there was one. Bregman believes humans are a kind species and that we should arrange society accordingly. The reason why this thesis needs intellectual support at all is not that it is particularly profound or complicated, but that there are so many misunderstandings to be cleared away, so many apparent objections that need to be overcome.

Rutger Bregman’s Humankind: A Hopeful History is a clearly written argument if ever there was one. Bregman believes humans are a kind species and that we should arrange society accordingly. The reason why this thesis needs intellectual support at all is not that it is particularly profound or complicated, but that there are so many misunderstandings to be cleared away, so many apparent objections that need to be overcome.